Dismay over rising premiums. Disputes over whether an illness is a pre-existing condition. Long waits for claims payments and tussles over proper claims documentation.

Dismay over rising premiums. Disputes over whether an illness is a pre-existing condition. Long waits for claims payments and tussles over proper claims documentation.

Familiar to anyone who uses private health insurance in the United States, such tensions these days involve not just human patients but dogs and cats, too.

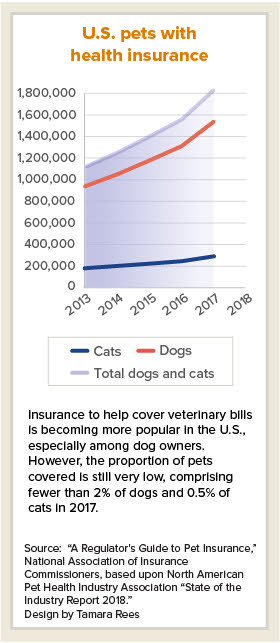

As American consumers increasingly buy insurance to help cover their pets' veterinary bills, state regulators are taking a closer look at a sector that, until recently, operated with inconsistent notice by the government.

A group of regulatory staff, working under the auspices of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), is drafting a model law on pet insurance in an attempt to bring coherence to pet insurance rules and protections for consumers.

Insurance is regulated by states, and the NAIC itself has no regulatory power but its members do.

The effort to develop a model state law began late this summer and could be completed in a year, according to the NAIC, which said the project was spurred by growth in the pet insurance market, along with regulatory investigations and disciplinary actions by a few states involving pet insurers.

Pet insurance accounts for an exceedingly slight share of the total property and casualty insurance market in the U.S. — $1.03 billion of $558.2 billion in premium volumes in 2017, judging from figures provided by the North American Pet Health Insurance Association and the Insurance Information Institute.

And only a small proportion of U.S. companion animals are insured: fewer than 2% of dogs and 0.5% of cats in 2017.

But the value of the market has been growing by double digits each year for at least five years. The increasing popularity of pet insurance is raising a variety of questions. The NAIC said development of a model law will entail discussion on a number of issues, including:

Licensing and authorization to sell pet insurance

Should someone selling pet insurance need a full property-and-casualty (P/C) insurance license or does a limited-lines license suffice? A limited-lines license is something that a travel agent, for example, would need to sell travel insurance, while a full P/C license is required of agents or brokers selling homeowners or auto insurance.

Complaint examples from one state

According to A Regulator's Guide to Pet Insurance recently issued by the NAIC, most states require a full P/C license to sell, solicit or negotiate pet insurance, but a handful of states permit a limited-lines license.

The question has implications for veterinarians' role in promoting pet insurance. Within the industry, according to the NAIC, some believe that requiring a full P/C license better protects consumers because vendors have more training and knowledge, while others maintain that there's value in having veterinarians be the first contact in an insurance sale because it's their services that are covered.

One gray area is whether a veterinarian or veterinary office that provides literature leading to a sale is considered to be engaged in selling insurance. According to the NAIC, a goal of the working group is to clarify what activities are allowed and not allowed by those working in veterinary practices and pet shelters who are not licensed to sell insurance.

The question is of growing importance to practicing veterinarians, who are being wooed by some insurers to actively support the sale and use of pet insurance. Trupanion, an insurer based in Seattle, ran afoul of Washington state law and paid a $10,000 fine this year in part because it had given pet-care providers gifts for referrals.

Practitioners are under pressure from within the profession, too, to promote pet insurance. The American Veterinary Medical Association in August adopted a policy that encourages veterinarians and their staffs "to proactively educate their clients about the existence of" pet insurance, reasoning that owners of insured pets can afford more care. The AVMA policy has met with mixed reviews by the veterinary community.

Consumer disclosures

Do consumers of pet insurance know what they're buying? Are they aware of what's excluded from coverage? Do they understand how "pre-existing conditions" and other policy terms are defined?

Sometimes, no. Common pet-insurance complaints received by the Washington insurance commissioner's office revolve around misunderstanding coverage limits and exclusions, said agency spokesperson Kara Klotz. "People will file a claim and it gets denied for things like pre-existing conditions, and they didn't understand what the policy covered or didn't cover," she said.

But unless state law specifies clear disclosures that an insurer failed to provide, consumer confusion doesn't constitute wrongdoing on the part of the insurance company. The same applies to other issues that elicit complaints, such as premium increases. If state law doesn't speak to the issue, there's no violation by the insurer.

California is the only state with a law specific to pet insurance. Enacted in 2015, the law requires policies sold in California to contain clear language explaining coverage limits, including co-insurance, waiting periods, deductibles and annual or lifetime limits. Consumers also must receive full refunds for policies canceled within 30 days of purchase.

To help inform prospective policyholders, the California Department of Insurance has suggestions on questions consumers should consider, beyond price, when buying pet insurance.

The NAIC pet insurance working group has posted a discussion draft of a model law that addresses disclosures and policy terms.

Gathering better data

To help regulators better track complaints, the NAIC working group advocates reclassifying how information is reported to states by pet insurers. Currently, pet insurance is categorized as "inland marine," placing it in the same group as insurance covering the shipping industry. That classification makes it difficult for states to monitor and tally consumer complaints and inquiries specific to pet insurance.

When the VIN News Service filed a public records request for pet insurance complaints in Washington state, for example, an official responded by searching the database for the words "pet" and "veterinary," which returned a list of mostly, but not completely, relevant hits. The search ultimately generated about 80 pertinent complaints during the past 3½ years. Whether that's a lot or not in the world of regulatory complaints is unclear — the state doesn't track the number of pet insurance policyholders.

At the national level, categorizing pet insurance separately requires changing a financial statement form that states require insurers to file each year, according to the NAIC. Making such a change does not happen quickly.

Public involvement invited

Developing the model law is a public process, and the NAIC accepts comments from the public. Materials and events related to model law are posted online. The first part of the proposed model — sections one through four of a nine-section draft — is up for comment through Oct. 31.

The group is scheduled to meet again by conference call on Nov. 7 to continue its discussion.

The working draft should be considered a starting point for discussion, not indicative of a final direction, according to NAIC; all issues are said to be up for discussion and an eventual vote. In addition, the group will take public comments on the full draft once it's completed.

States aren't obligated to adopt an NAIC model law, but the majority usually do within three years, according to the organization.