Proposal limits waiting periods for coverage, sets boundaries on wellness plan sales

!This story has an important update

In the seven years since California became the first U.S. state to adopt a law specifically on pet insurance, no other state has followed.

In the seven years since California became the first U.S. state to adopt a law specifically on pet insurance, no other state has followed.

That might change if an association representing insurance regulators from across the country approves next week a pet insurance model law that's intended to inspire action by states.

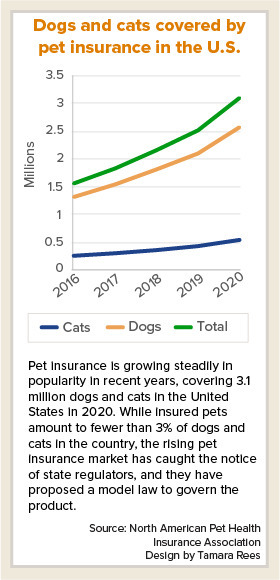

The model is meant to provide clarity and nationwide consistency in policy provisions and disclosures of pet insurance as sales of the product rise. The total number of insured dogs and cats, about 3.1 million, amounts to fewer than 3% of their estimated population in the U.S., but the industry is expanding apace. According to the North American Pet Health Insurance Association (NAPHIA), the number of insured dogs and cats in the U.S. grew at an average annual rate of about 19% between 2016 and 2020.

The model law was developed over two years by a working group of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), whose 56 voting members represent 50 states, the District of Columbia and five U.S. territories.

Acceptance by the full NAIC requires approval by two-thirds of its members, or a supermajority. A "yes" vote means a member "will make efforts to have the model law introduced into his or her respective state legislature," unless their state already has a law that meets or exceeds the standard set by the model law, according to the NAIC.

The one state law in place, California's, is less stringent, chiefly requiring clear language and disclosures.

Asked whether the state would amend its law to more closely match the model, assuming it's adopted, the California Department of Insurance replied by email: "California supports the model in its current form and we will determine next steps after the [NAIC] meeting."

While pet insurers as a whole support having a model law, the more rigorous provisions of the proposed legislative template have caused them consternation. One limits waiting periods for coverage to no more than 30 days. Another requires sales of wellness plans to be conducted separately from sales of insurance policies because wellness plans are not insurance.

During meetings of the working group, which were held remotely and open to the public, discussions on waiting periods were contentious, particularly during one gathering in July. Insurance representatives argued that waiting periods of up to 120 days for coverage of certain conditions — orthopedic conditions in dogs in particular — or for circumstances such as accidents, are needed to avoid having to pay claims for problems that were brewing before the pet's owner bought insurance.

They argued that longer waiting periods benefit consumers by reducing the cost of claims, enabling insurers to offer lower premiums.

Consumer advocate Birny Birnbaum, a former insurance official in Texas and now executive director of the Center for Economic Justice based in Austin, countered, "Why not just give them a pretend policy that gives virtually no coverage and sell it for 12 cents? That would be great, according to this logic."

Regulators, too, were unpersuaded that long waiting periods are justified. "One hundred and twenty days, what is that — a third of the annual policy?" said David Forte, a policy analyst in the Washington state Office of the Insurance Commissioner.

Others in the group suggested long waiting periods might result in pet owners delaying needed veterinary care for their pets, causing their conditions to worsen and potentially cost more to treat later.

Cari Lee, representing the trade group NAPHIA, warned the working group that "the waiting period language will be a line in the sand ... and will likely result in us opposing the model."

In the end, the regulators settled on waiting periods of no more than 30 days, and NAPHIA opted to neither support nor oppose the model.

The group's executive director, Kristen Lynch, said in an interview that being allowed no waiting periods at all would be very difficult for insurers but a shortened waiting period, "we can live with."

She said the trade group favors having a model law because it promotes uniformity in how states regulate pet insurance. "Uniformity saves money," Lynch said.

As individual states take up pet insurance legislation, Lynch said, the group will continue to advocate for longer waiting periods: "We know we're going to need to go state to state to talk about this."

Another aspect of the model law that's caused the insurance lobby hesitation concerns wellness plans.

While pet insurance is also known as pet health insurance, it is different from health insurance for people. Regulators categorize pet insurance as property insurance because the law treats pets as property. So if a pet insurer offers a plan for wellness services such as vaccinations or dental cleaning, generally, that wellness plan is not considered insurance and therefore is not subject to consumer protections governing insurance. (The same is true of wellness plans offered by veterinarians: The plans are not insurance.)

As Lynch explains, "Pet insurance is planning for the unknown, and wellness is planning for the known."

To underscore the distinction, the model law specifies that wellness programs cannot be marketed as pet insurance, nor can insurers require that a pet owner buy a wellness plan as a condition of buying pet insurance. Further, wellness plans cannot be marketed during the sale, solicitation or negotiation of pet insurance.

While NAPHIA agrees with the concept, Lynch said the group is puzzled by precisely how the prohibition would work. For example, in the context of online sales, "We're trying to determine, does that mean you have to leave the [web]site?" she wondered. "... Or does it just make sense to disclose that wellness isn't pet insurance? ... It already is two separate lines on the bill."

Working out that detail is an aspect, like the limit on waiting periods, that the organization will try to address on a state-by-state basis.

Birnbaum, the consumer advocate, said in an interview that he is generally satisfied with how the model turned out. He identified as strong points the limit on waiting periods, as well as a requirement that producers (that is, insurance salespeople) undergo training. "I suspect that the model is sufficiently balanced to generate industry opposition because it doesn't simply memorialize current industry practices ..." he said.

Although the industry advocated for a model law, regulators' attention to the topic was drawn by consumer complaints, as well. Complaints include issues such as rising premiums, definitions of pre-existing conditions and long waits over claims payments.

Whether pet insurance is a smart buy is an open question with plenty of ifs, ands and buts. Consumer Reports observes: "If you're unlucky enough to have a pet with a costly chronic condition or an illness, you might get a positive payout from a plan. But it's a roll of the dice; many policies may not be worth the cost over many years for a generally healthy animal."

One aspect the Pet Insurance Working Group considered but did not resolve is the level of licensing that should be required for those selling pet insurance. The issue might have ramifications for veterinary staff that wish to recommend or highlight particular insurance products. The question was referred to a different working group.

NAIC members will review the model law during a meeting Thursday in San Diego. If it's approved, the NAIC's goal is that states adopt it in the next three to five years.

Update: The pet insurance model law was pulled from consideration by the full NAIC on Dec. 16. A reason was not provided to the public. An email from NAIC staff states, "We will continue working on the model act and present it for a vote at a later date, most likely at the spring national meeting. We have no additional information at this time."