American Veterinary Medical Association economists labeled 2015 veterinary graduates as either "frugal" or "excessive" depending on their accumulated educational debt, in the recent "AVMA 2015 Report on Market for Veterinary Education."

An executive summary of the work is publicly available; the full 60-page document is not. Published in October, the report is part of a series of economic studies that AVMA members can purchase for $249. (Editor's note: The AVMA's 2015 economic studies became publicly available in April via ResearchGate.com. Users must register and log in with the online network to access the documents.)

The report's principal contributors are Michael Dicks, director of the AVMA Economics Division, AVMA economic analyst Ross Knippenberg, and Bridgette Bain, the AVMA's statistical analyst. Lisa Greenhill, a researcher and associate executive with the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, also is listed as a contributor.

That's a reputable list of authors. However, we think the terms they use are judgmental, subjective and have no place in an objective analysis. In the context of the AVMA's report, "frugal" and "excessive" are careless descriptors for student indebtedness — a topic that is phenomenally more complex.

The AVMA based its findings on students' self-reported levels of educational debt and an estimated cost for a veterinary education at their respective colleges. Those who report debt less than the estimated costs are considered frugal, while those who do not are considered to have excessive debt.

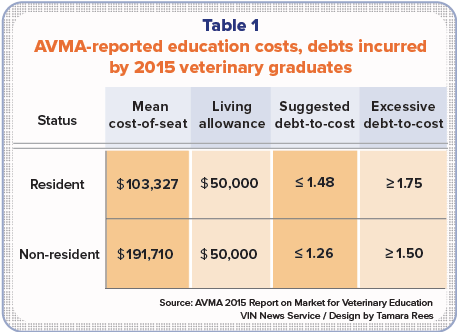

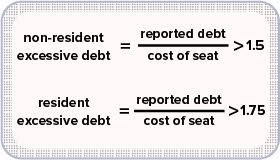

The report established what AVMA economists consider to be an excessive debt-to-cost ratio: "There is a small group of graduates who have debt levels that are excessive. These debt levels have a large impact on the average level of reported debt for the profession. When we break down the percentage of 2015 graduates by debt-to-cost ratio, we have identified 27.2 percent of resident graduates with greater than a 1.75 debt-to-cost ratio and 16.1 percent of non-resident graduates with greater than a 1.5 debt-to-cost ratio. We believe that better financial management on behalf of and by these individuals during their veterinary college years would reduce their level of debt."

The report also finds that large groups of heavy educational debtors are concentrated at certain colleges.

We agree that efforts to improve the financial acumen of graduates are needed to help students minimize the total cost of their education. But the AVMA analysis oversimplifies the debt situation for veterinary students by failing to account for each college's published cost of attendance (COA) and the cost of borrowing.

Given the definition of COA, a student's debt is not just a product of the borrower's circumstances and behavior. The total they owe at graduation and ultimately will be responsible to repay is driven, as well, by the federal student loan borrowing system and how each college interacts within that system. Collectively, we can develop better tools and strategies for establishing realistic cost thresholds if everyone — students, colleges and those studying student debt — better understand how financing education works.

According to the AVMA report, the "average four-year cost of resident and non-resident seats for the 2015 graduates was $103,327 and $191,710, respectively. Average four-year debt of the 2015 graduates who filled those seats was $132,560 and $187,379, respectively. These mean values of costs and debt suggest that, on average, the 2015 graduates were financially frugal.

"Considering a four-year living allowance of $50,000, the amount of loans needed to cover all tuition and living expenses would be 1.48 times the cost of the seat for residents, and 1.26 times the cost for non-residents," the report continued. "Debt-to-cost levels above this indicate a problem with personal financial management."

Table 1 (above) summarizes the cost, debt and debt-to-cost ratio for 2015 veterinary graduates, as reported by the AVMA. (AVMA economists refer to "cost-of-seat" and "cost-per-seat" interchangeably throughout their paper. To use more common language, we also refer to these terms as "tuition and fees.")

The debt-to-cost ratios defined by the AVMA as excessive are arbitrary and inexact because they fail to account for the costs some students incur when they borrow for their program's COA. We suggest that a more accurate measure would be a debt-to-COA ratio.

While AVMA economists analyzed many U.S. veterinary colleges, we are intimately familiar with how borrowing works for Colorado State University's (CSU) veterinary program. So let's use CSU to illustrate the differences between AVMA's debt-to-cost ratios versus the debt-to-COA ratios.

The report states that the CSU veterinary program is among those where non-residents graduating in 2015 reported "…levels of debt less than would be expected given the cost per seat …" At the same time, 12 to 13 percent of CSU's resident veterinary students borrowed "excessively," the report said.

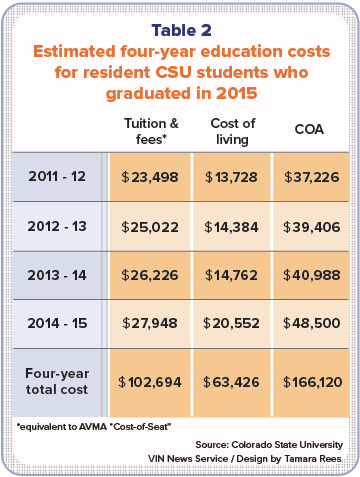

Consider that the resident cost-per-seat (tuition and fees) for four years at CSU's veterinary college totaled $102,649 for 2015 graduates.

That's coincidentally close to the mean $103,327 that the AVMA economics team reported when it analyzed U.S. programs.

That's coincidentally close to the mean $103,327 that the AVMA economics team reported when it analyzed U.S. programs.

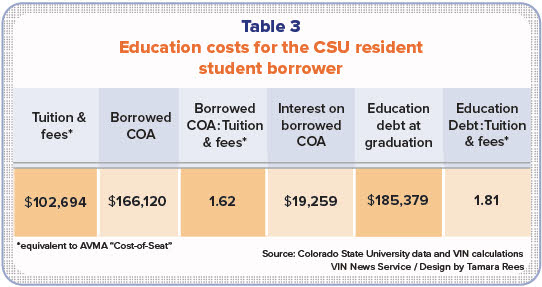

CSU veterinary students, however, are permitted to borrow what the college publishes as its COA. CSU's COA estimates living expenses to be $63,436 over four years, nearly $14,000 more than the $50,000 that AVMA economists report is reasonable for living expenses. Thus, a CSU resident student's federal student loans can total 1.62 times the cost of his or her seat in order to cover the COA (Borrowed COA:Tuition & Fees, Table 3), which is greater than the AVMA's suggested debt-to-cost.

If resident students can borrow enough to cover a college's COA and that maximum is more than what the AVMA deems excessive (1.75 times the AVMA-defined cost-per-seat), is it appropriate to label the debt reported by 12 to 13 percent of the 2015 resident students at CSU as excessive?

Student loans aren't free

Also not mentioned in the AVMA analysis is the interest that accrues on federal student loans while the borrower is in college. Accumulated interest on the default federal student loans available (Direct Unsubsidized and Direct Grad Plus) to cover CSU's COA for a class of 2015 resident veterinary students adds $19,259 to the debt balance by the time of graduation. That brings the total educational debt to $185,379, and the debt-to-cost ratio to 1.81-to-1 (Education Debt:Tuition & Fees, Table 3), well into the realm of what the AVMA economists deem excessive.

Thus, any resident student who borrows the full COA to attend CSU will graduate with "excessive debt," as defined by the AVMA economists.

If resident students can borrow enough to cover a college's COA and that maximum is more than what the AVMA deems excessive (1.75 times the AVMA-defined cost-per-seat), is it appropriate to label the debt reported by 12 to 13 percent of the 2015 resident students at CSU as excessive?

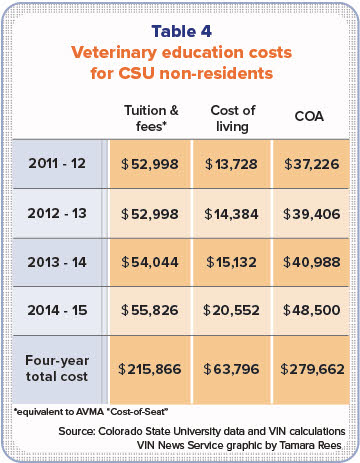

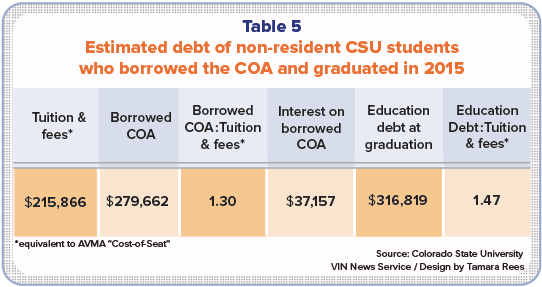

Let's apply the same analysis to a hypothetical CSU non-resident borrower graduating in 2015 (Table 4). The tuition and fees for a non-resident CSU graduate in 2015 is $215,866, which is 12.6 percent higher than the mean $191,710 reported in the AVMA's analysis.

Referring back to the first table, the AVMA-suggested debt threshold is 1.26 times the cost of the average seat for all non-residents. The COA for a non-resident student graduating from CSU in 2015 was $279,662, 1.3 times the cost of a non-resident seat (Borrowed COA:Tuition & Fees, Table 5). Again, the college-determined COA is greater than the AVMA's suggested average debt range.

Borrowing higher sums results in more interest accrued prior to graduation. In this example of a non-resident 2015 graduate who borrowed CSU's full COA, interest adds $37,157, resulting in $316,819 in educational debt by graduation. That's 1.47 times the AVMA-defined cost-per-seat (Education Debt:Tuition & Fees, Table 5) — not what the AVMA labels excessive, but a debt-to-cost ratio of 1.47 for a non-resident student still is described by the economists as "… a problem with personal financial management."

Borrowing higher sums results in more interest accrued prior to graduation. In this example of a non-resident 2015 graduate who borrowed CSU's full COA, interest adds $37,157, resulting in $316,819 in educational debt by graduation. That's 1.47 times the AVMA-defined cost-per-seat (Education Debt:Tuition & Fees, Table 5) — not what the AVMA labels excessive, but a debt-to-cost ratio of 1.47 for a non-resident student still is described by the economists as "… a problem with personal financial management."

Does every non-resident CSU veterinary student who borrows the COA have a problem managing money? Do AVMA economists mean to suggest that unless a student has a way to pay at least some of the expense of veterinary college upfront, he or she is making a poor financial choice to attend veterinary college?

And if a student is fortunate enough to pay less than the AVMA-advised debt totals, is that student truly frugal, as economists suggest?

What does frugal mean, anyway?

Quoting from the report, "These mean values of costs and debt suggest that on average, 2015 graduates were financially frugal." The AVMA economists consider it frugal to borrow less than their suggested-debt-to-cost (Table 1) to earn a four-year veterinary degree. That outcome, however, might have more to do with a student's individual situation and how he or she interacts with the federal student loan system than his or her financial management skills and behavior.

Were CSU graduates who reported their "less than would be expected" debt levels truly frugal, or did they:

- underreport their educational debt because they weren't informed how to do so accurately?

- receive good borrowing advice and/or education?

- have more financial support from family?

- receive more scholarships and/or grants?

- know how to reduce and/or return awarded funds that exceeded their needs?

- disproportionately respond to the survey compared to those who borrowed the full COA?

Apart from procuring outside funds or more scholarships and grants, no reliable method exists to drive down personal education costs without limiting the future of the veterinary profession to those who can afford it or are willing to rack up six-figure student loan debt. More than half of veterinary students receive no grants or scholarships. According to recent analysis by the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, those who do receive $2,488 per year, on average.

Conversely, unless students go to the private student loan market, they cannot borrow more than what the college publishes as its COA. Our experience working with students and new graduates suggests that few borrow from private lenders to pay for veterinary college.

Why 'graduates with excessive levels of debt are congregated in specific colleges'

The AVMA report doesn't just label students based on indebtedness. The economists also focused on veterinary colleges, identifying 13 programs in the United States where an inordinate percentage of the student body carries high student loan debt. Seventy percent of non-resident veterinary students at Tuskegee University, for example, graduated last year with debt more than one-and-half times the cost of their seat. Western University of Health Sciences came in a close second.

Without access to the AVMA's raw data, we cannot assess all the reasons why Tuskegee and Western are among those named in the AVMA's report. Nor can we fully examine how the economists came to find that "excessive levels of debt are congregated in specific colleges." The answer to this is an open question and fodder for future research.

We suspect, however, that the rules governing the federal student loan system, how the schools determine their COA and how the AVMA accounted for resident and non-resident students (see sidebar titled "Problem school or problem analysis?") might have something to do with their conclusion. Tuskegee and Western are labeled by the AVMA report as having resident and non-resident tuition rates. In reality, those colleges have a single tuition rate; Tuskegee changed to that structure during the period analyzed by the AVMA.

A closer look at 'excessive' debt

Again, AVMA economists deem a student's debt excessive when it is 1.75 times the cost of a resident seat and 1.5 times the cost of an non-resident seat. And their analysis assumes that no more than $50,000 is needed to cover four years of cost-of-living expenditures.

This assumption ignores the fact that each veterinary college reports appropriate cost-of-living expenses, as defined by the COA. It also ignores the costs associated with loan origination fees as well as accrued interest.

It is a simple mathematical reality that students are more likely to be classified as having excessive debt (a ratio of reported debt to cost-per-seat) if they report high student loan debt and low tuition and fees. This is most likely if students:

- borrow the full COA.

- properly report their expected debt at graduation, including accrued interest.

- attend a school with published cost-of-living allowances higher than $50,000.

- attend a school with lower tuition rates and fees.

Before we make judgments about students' borrowing behavior, it is important that we understand the student loan borrowing process, and set a threshold for what we define as excessive based on each veterinary college's COA, plus interest. If a student borrows more, there could be a good reason why his or her costs are higher — reasons that have little to do with lavish or frugal spending behavior.

This is the reality for all who use federal student loans to finance most or all of their colleges' COA, and especially for those who do not have the means to reduce their amount borrowed (such as by being born into wealth or having money accumulated from a prior career, or other sources). Failing to recognize and address this reality may impact the profession and make it difficult to attract the best and brightest from all sectors of society, rather than limiting it to only those who can afford to pay.

Problem school or problem analysis?

Analysis underestimates debt situation

Because the AVMA senior survey — one of the reports on which the AVMA's economic report is based — is conducted prior to graduation, the results are skewed. Even if all students provided data that's accurate on the day they responded to the survey, they would underestimate their starting repayment balances because the interest on their loans will continue to accrue as they head toward graduation and the end of their repayment grace period, six months post graduation.

The AVMA report states that while a small number of graduates have excessive debt levels, that group has a "large impact on the average level of reported debt for the profession." While the AVMA might consider this "small group" of excessive borrowers to be outliers inflating the overall indebtedness picture, what will the debt situation look like when the analysis includes the graduates of pricey foreign programs and new domestic colleges at Lincoln Memorial and Midwestern University?

The recent report also fails to consider the educational debt of hundreds of Americans graduating each year from U.S.-accredited foreign programs in the Carribean, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, where earning a degree in veterinary medicine costs more than it does at a domestic program.

Having studied how borrowing works for veterinary students attending veterinary school at Glasgow and Dublin, exchange rates and the encouragement of classmates and schools to borrow the full COA have resulted in recent graduates owing more than $400,000 of veterinary educational debt. Some of the first half-million-dollar veterinary graduates are due to complete these foreign programs in three to four years.

Approximately 25 percent of all American veterinary students will complete their education at a college not included in the AVMA's 2015 analysis. When the AVMA starts including those students, debt now deemed to be excessive might look more like the norm.

Before we can hope to fix the educational debt issue facing veterinary medicine, we must get serious about finding a way to count all U.S. citizens who are eligible to borrow federal student loans, no matter what AVMA-accredited institution they attend. Complete and accurate reporting, as well as effective debt education, should be required for accreditation.

How can we help students borrow less?

To help veterinary students reduce their education spending, we must implement more consistent student loan education and transparency around the factors that impact costs. Advising students to borrow only what's needed for their circumstances and not all that's offered by the federal government could go a long way toward easing debt burdens.

Colleges must accept more responsibility for educating students about their evolving borrowing and repayment options, and reinforce that information every time student loans are disbursed.

Finally, the AVMA report hypothesizes that "the major problem in the veterinary profession is that the expectations about lifestyle exceed what actually occurs." If we continue to ignore the current borrowing realities facing many veterinary students and offer unrealistic debt-to-cost thresholds for what is defined as "excessive" or "frugal," we will exacerbate the frustration associated with mismatched expectations.

Let's build on what AVMA economists have reported, improve the quality of the data and accept our responsibility to better understand and discuss the true cost of a veterinary education (COA plus student loan interest) so we can effectively inform and guide our future colleagues and better match their expectations with reality.

About the authors: Tony Bartels, DVM, MBA, is a 2012 Colorado State University graduate and employee of the Veterinary Information Network. His professional interests include small animal and exotic medicine, educating colleagues on veterinary student loans and repayment strategies, and advocating for internship quality control. When he’s not staring holes into his family’s student-loan statements, he enjoys spending time with his wife Audra, a small animal internal medicine specialist practicing in Denver. Other family members include a back-alley street mutt named Herbie, a recently rescued labradoodle named Addison and a tortoise named Leo, who now occupies a rather large territory in Arizona. During his free time, Dr. Bartels enjoys stopping a few shots on the ice as a goaltender and fly fishing.

Dr. Paul D. Pion is a board-certified veterinary cardiologist and co-founder of the Veterinary Information Network, an online professional community and parent of the VIN News Service. He earned his DVM from Cornell University in 1983 and completed a residency in cardiology at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine in 1987. Among his many accomplishments, he is credited with discovering the cause, cure and prevention of feline dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to taurine deficiency. Dr. Pion resides in Davis, California, with his wife, children and a plethora of pets.