Maine has become the second state in the country, after California, to enact a law explicitly about pet insurance.

Maine has become the second state in the country, after California, to enact a law explicitly about pet insurance.

The legislation, signed by the governor this spring, takes effect Jan. 1. It is based on a draft model law developed by a working group of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), which aims to provide clarity and consistency in policy provisions and disclosures of pet insurance as sales of the product rise.

Provisions of the Maine law include giving consumers the right to a premium refund within 15 days of payment, unless they have already filed a claim; a limit on waiting periods of no more than 30 days; a ban on requiring a medical exam in order to renew a policy; and a prohibition on marketing wellness programs at the same time that pet insurance is solicited, negotiated or sold. (Wellness plans, which generally provide prepaid preventive and routine care, are often sold by insurers as well as veterinary practices but are not insurance products.)

Maine Sen. Heather Sanborn, who sponsored the law, said she submitted the bill in late 2020, more than a year after the NAIC pet insurance group began its work. She expected that the model law would be completed before the end of her state's two-year legislative session.

But as the session drew to a close this spring, the model hadn't been finalized. Sanborn opted not to wait.

"We decided to go forward, in part because we were running out of legislative time and the next chance would be next spring, and I'm not running for re-election," she explained in an interview Monday. "It was something I wanted to accomplish."

The owner of two insured pooches, Sanborn said, "There are also a lot of dog lovers at our Bureau of Insurance, and they'd been tracking [the NAIC group's progress] and were quite supportive of the model."

Sanborn said she and state insurance officials figured the law could be amended later if need be, so she adopted language from the unfinished model.

The Maine bill proved popular. Although pet insurance industry lobbyists objected to aspects such as the provision separating sales of wellness plans from insurance, Sanborn said, the legislation received full support from the Joint Standing Committee on Health Coverage, Insurance and Financial Services, which she chairs. The bill then passed both House and Senate by unanimous consent. The governor signed the legislation on April 7.

The NAIC pet insurance working group, meanwhile, met again today. It was the first time the group convened since last year, when it appeared to have completed writing the model law. The draft was set to be reviewed and potentially approved at a meeting of the full NAIC in December. But at the last minute, the draft was pulled from consideration with no public explanation.

At today's meeting, working group chair Don Beatty, who is associate general counsel at the Virginia State Corporation Commission, offered this: "What happened was, we adopted a model, recognizing our brilliant work. However, at the fall national meeting, there was concern about section 7. And so the draft model was pulled from the executive plenary agenda."

Section 7 involves training for insurance "producers," a term in the industry for people who are licensed to sell insurance products. The version of the model previously adopted by the group included an extensive section on training, including a specified number of hours and ongoing continuing education, along with information to be covered, namely: pre-existing conditions and waiting periods; the differences between pet insurance and non-insurance wellness programs; hereditary disorders, congenital anomalies or disorders, chronic conditions and how pet insurance policies interact with those conditions; and administrative topics such as rating, underwriting and renewal.

As a result of unspecified discontent over the section, the working group considered eliminating the specifics, leaving all mandatory training details for individual jurisdictions to determine. However, it did not make a decision. "Today's meeting, we're going to go over the proposed changes ... and after this meeting, we'll expose those changes for comment and hold another meeting in a few weeks with the objective of adopting a model and moving it forward," Beatty said.

Kendra Zoller, deputy legislative director of the California Department of Insurance, said she'd reject the revision: "Unfortunately, we would oppose this change because it does not provide uniformity and defeats the purpose of a model law."

George Bradner, director of the property and casualty division of the Connecticut Insurance Department, noted that as the model law is just that — a model — states could follow or reject any of its aspects, including CE and training recommendations. He suggested adopting both the old and newly proposed versions of section 7, presenting them as options. That way, "states could choose either version and make the necessary adjustments that would align with their state needs," he said.

Once finalized, the document will not by itself have legislative authority, although the NAIC, whose 56 voting members represent 50 states, the District of Columbia and five U.S. territories, expects that member jurisdictions will adopt it in some form within a few years.

The new Maine law retains the more prescriptive training requirements specified in the earlier version of the draft, which Sanborn cheerily pointed out is consistent with the idea of leaving particulars to the states. "We get to decide!" she said.

At the same time, there may be tinkering ahead on the Maine law. Sanborn said some licensed health insurance brokers in the state would like to be able to obtain an endorsement on their license that would enable them to sell pet insurance — "so they could sell health insurance for the whole family."

Allowing for that may be possible, she said, even though pet insurance technically is regulated as property and casualty insurance, not health insurance.

In fact, it was consumer confusion about how pet insurance differs from health insurance for people that piqued Sanborn's interest in pet insurance legislation.

"The paradigm under which it's regulated doesn't really match consumers' expectations about what coverage they will receive," she said. "They expect pet insurance to behave a lot more like the health insurance they're familiar with. ... So trying to match the regulatory paradigm more closely to consumer's expectations, I think, will help people understand better what they're buying."

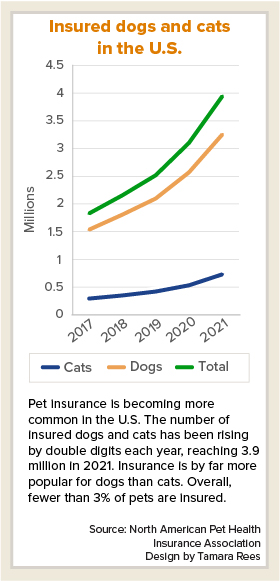

According to the latest figures from the North American Pet Health Insurance Association, nearly 4 million dogs and cats in the United States were insured in 2021, an increase of more than 28% over the previous year.

While the growth rate is high, the total proportion of pets insured remains modest at just under 2.5%.