Compliance deadline for new hazardous drug safety standards is Dec. 1, 2019

A new federal standard designed to protect the safety of health-care personnel who handle hazardous drugs has sparked confusion and concern among veterinarians who fear that the change will complicate their jobs.

A new federal standard designed to protect the safety of health-care personnel who handle hazardous drugs has sparked confusion and concern among veterinarians who fear that the change will complicate their jobs.

Veterinarians posting to message boards of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, question the feasibility of implementing the United States Pharmacopeial Convention's General Chapter 800, "Hazardous Drugs — Handling in Healthcare Settings," in private practices.

Some clinicians wonder whether the additional paperwork and infrastructure needed to comply with USP 800 — for example, the externally ventilated, negatively pressurized room and hazardous materials gear required to unpack or mix medications — will complicate stocking and administering chemotherapy drugs and other such medications in their practices.

Equally unclear is the role state veterinary regulators will play in the enforcement of USP 800.

USP is not a regulatory body; it's a scientific, nonprofit group that recommends standards for medicines, food ingredients and dietary supplements. USP 800 lays out safety and handling standards for drugs listed as hazardous by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The guidelines cover new requirements for personnel handling hazardous drugs; facility and engineering controls; procedures for deactivating, decontaminating and cleaning; spill control; documentation; and medical surveillance.

The new rules, initially published on Feb. 1, 2016, are expected to become official on Dec. 1, 2019. The changes apply to all health-care workers, including veterinarians and veterinary staff, and are set to coincide with revisions to USP 797, the agency's chapter on sterile compounding.

The United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) characterizes the importance of USP chapters 800 and 797 on the agency's web page: "... USP 800 focuses explicitly on protecting workers from exposures to hazardous drugs. It, and USP 797, represent professionally expected requirements in health care that incorporate national consensus standards on infrastructure maintenance."

Regulatory landscape

Veterinary medicine and pharmacy are two distinct professions, each regulated by state laws that are enforced by separate licensing boards. Unlike human medical practices, veterinarians often administer drugs and fill prescriptions from their own in-house pharmacies.

The convergence of the two professions is where rules for practitioners become fuzzy. Typically, a state board of pharmacy would act as the enforcement authority for USP 800 and other regulatory chapters, ensuring that pharmacies they license abide by them.

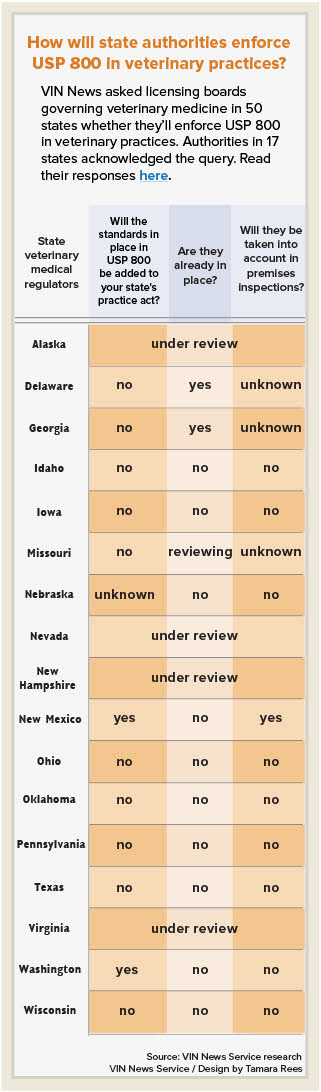

But veterinarians are not licensed by pharmacy boards, and it's unclear what role veterinary boards might take in enforcing the standard. In an attempt to clarify the ramifications of USP 800 for veterinary practices, the VIN News Service posed questions to veterinary licensing boards in every state:

- Does your state veterinary medical practice act reflect standards set by USP 800?

- If not, are changes anticipated?

- Will compliance with USP 800 be considered during the inspection of veterinary practices?

Thus far, officials with 17 state licensing agencies have answered. Their responses range from "no" to detailed explanations of state laws. Many regulators deferred to hazardous drug-handling laws and state boards of pharmacy, further muddying efforts to extract clear answers.

Authorities representing 33 state veterinary licensing agencies did not respond to the query. (See sidebar.)

Evolving attitudes about drug safety

USP 800 is unusual among guidelines impacting veterinary practitioners in that it was spearheaded by one of their own — Dr. Brett Cordes, whose life was interrupted in the early 2000s by a cancer diagnosis.

As he started treatment and considered the possible causes of his disease, Cordes said he began to think critically about where he worked and how he practiced. "I used to work in a vet clinic when I was a teenager and didn't know about [the potential exposure to carcinogens]," he said. "… As a young kid, I worked in an oncology facility, taking radiographs and cleaning kennels full of metabolites."

With the belief that early exposure to hazardous substances prompted his illness, Cordes set out to educate his colleagues. He left practice and spoke with a number of other relatively young veterinarians with cancer and other illnesses.

"I wanted to be part of the solution," he said. "We focus on the animals and don’t take care of ourselves. I didn’t want that to be our profession."

Cordes took his concerns to Washington, D.C., where he met with USP officials. "At the time, everyone was talking about safe handling of drugs in human health care settings. But veterinarians were starting to get access to generic chemotherapeutics."

Describing the agency's realization that veterinarians handle hazardous drugs, too, he added: "That conversation at USP was interesting. I never thought it would turn into something that would change health care globally."

Cordes went on to co-author the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) paper, "Safe Handling of Hazardous Drugs for Veterinary Healthcare Workers." Updated in July 2010, it provides instructions regarding infrastructure, personal protective equipment and worker training.

Now healthy and practicing in Arizona, Cordes makes sure his clinic heeds safety guidelines. "USP 800 is designed to make sure all practitioners in any setting are prepared to handle hazardous drugs," he said.

He urges colleagues to discuss with pet owners the ramifications of living with animals that are undergoing treatment with hazardous medications. Experts with NIOSH warn that owners can unwittingly expose themselves to a pet's medications if they have contact with the animal's urine and feces or handle pills and transdermal products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration echoes that message, warning that caregivers can accidentally ingest or absorb through their skin chemotherapeutic agents and other medications, such as those containing the antithyroid drug methimazole.

Cordes said he relays the risks to clients: "When I have a dog with cancer, I talk to people about those decisions. Often, it steers people away from wanting chemo. With methimazole [an antithyroid drug], it’s the same thing. We talk about that with our clients.

"It’s changed the way we treat hyperthyroid cats," he added. "We do thyroidectomy [removal of the overactive thyroid gland] more often than not. I strongly discourage topical methimazole."

Education resources

Cordes advises colleagues struggling to understand and implement USP 800 to "partner with people who are trying to help you."

He points out that vendors selling protective equipment and other drug safety products often can guide veterinarians as they navigate the USP chapter. Another source is VIN, parent of the VIN News Service, which addresses frequently asked questions about USP 800. The document is available to members.

Technology can help, too. In January, USP launched <800> HazRx, a mobile app that combines information from NIOSH, RxNorm and USP 800. The app, which retails for $3.99 for Apple and Android devices, is not veterinary specific. It allows users to search drugs by name, identify those the USP considers to be hazardous, and get information on how to safely handle them. The app's glossary includes definitions for a number of hazardous drug-handling terms.

USP offers an eight-hour online course on USP 800 for $595. The webinar, scheduled March 21, will cover standards to protect personnel, patients and the environment when handling hazardous drugs; provide an overview of USP 800; describe personnel responsibilities; and outline cleaning and documentation requirements.