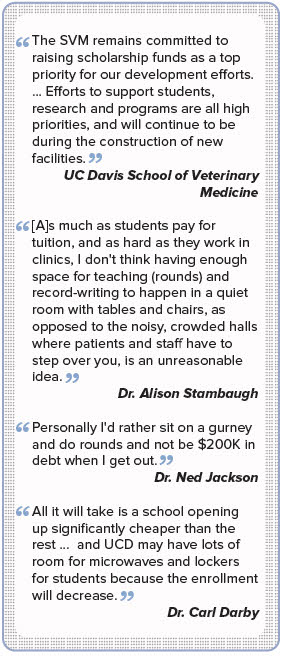

Artist's rendering courtesy of UC Davis

An updated small animal clinic is one of many facility upgrades planned by the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine during the next 10 years.

The University of California, Davis, is planning a major renovation and expansion of its veterinary teaching hospital that will nearly double the size of the existing facility at a cost that's 13 times the original building price in 1970.

At 431,152 square feet, the planned veterinary medical center (VMC) is designed to serve 50,000 patients per year in several new state-of-the-art buildings and in the remodeled hospital. The existing hospital was built nearly 50 years ago to handle 3,000 patients a year.

The half-billion-dollar endeavor is drawing excitement in some quarters and in others, dismay because it comes in an era of heavy financial strain for the newest generations of veterinarians. Average veterinary student debt in the United States is more than twice average starting salaries, and while tuition has flattened somewhat in recent years, the cost of becoming a veterinarian remains high — ranging from $143,000 to $366,000 over four years, including living expenses, according to calculations by the VIN Foundation.

Dr. Michael Lairmore, dean of the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, declined to be interviewed. A written statement attributed to Lairmore by the school's communications and marketing department said that funds designated for capital projects cannot be channeled toward reducing the cost of education.

“Funds raised from donors, or allocated by the university, for capital projects are specifically received and directed for this purpose and cannot be used for other purposes,” the statement reads. “Approximately 5 percent of the overall Veterinary Medical Center budget is being provided by the university from an infrastructure account – restricted for use to improve the facilities throughout the campus.

“The other 95 percent is being generated from grateful hospital clients and donors to the school specifically for the Veterinary Medical Center project. The question of redirecting these funds to alleviate student tuition and reduce student debt is often raised, but is not possible due to the terms of the funding.”

With formal fundraising yet to begin, construction dollars are not secure. The school started informally raising money in 2015 and expects to have $57 million or so in hand when it begins a public campaign this fall or next spring. The project is divided into phases, with the first phase priced at $115 million.

“Our objective at the time we move into the public phase ... is to have raised at least 50 percent of the $115 million goal,” the school says. “Based on current commitments received to date, we will be well ahead of that benchmark.”

The first phase includes a Large Animal Support Facility, Livestock and Field Service Center, All-Species Imaging Center, Equine Performance Center and site development.

The existing 230,400-square-foot teaching hospital was built in 1970 for $6 million, which equates to about $38 million today.

The school notes that the 47-year-old facility is expensive to operate because of its aging infrastructure, and that simply updating it to modern standards and technology would cost more than constructing anew. Moreover, “its design does not readily facilitate implementation of cost effective energy and green building solutions nor permit cost effective mitigation of environmental and occupational safety code changes for our staff, students, and faculty ...”

As an example of how the new design will “revolutionize care and student learning,” the school points to its proposed horse arena: “Currently, items such as force plate testing and gait analysis cameras are only available in laboratory settings. Due to space constraints, these items are not available for clinical application. The VMC arena will allow for a combination of clinical and laboratory settings to better serve our equine clientele.”

In a campus article about the planned upgrade, Dr. Sarah le Jeune, chief of the Equine Integrative Sports Medicine Service, explains, “[C]ertain injuries only become apparent when the horse is ridden, and we are currently missing this piece of information due to our small arena.”

Dr. Alison Stambaugh, a 2012 alumna, attests to the need for more space. “It is embarrassing to me how tiny the small animal ER and ICU are, and how crowded they can get when it's busy, and that student rounds for some services were commonly held in the hallways, sitting on the floor,” Stambaugh wrote on a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession.

“A lot of records get written while sitting on gurneys in the hall too, for lack of dedicated workspace on most services,” Stambaugh continued. “The wards are a chaotic mess at treatment times, with too many human and animal bodies running around too little space — who knows how many errors that leads to, and how that affects student stress levels.”

She added: “Maybe the services that currently all share a set of exam rooms could see more appointments if there were more rooms — I remember some services having to pounce on exam rooms as soon as they opened, because there weren't enough to go around. If there were more operating rooms and anesthetic induction/recovery space, maybe it wouldn't take two months for my referred patients to get their non-emergent orthopedic surgery.”

Other schools updated for less

Veterinary schools at the University of Georgia and Cornell University just completed or are in the midst of capital projects at a markedly lower cost.

Georgia's project, finished two years ago, enlarged the veterinary hospital and classroom space fivefold, from 60,000 square feet to 310,000 square feet, at a cost $97 million. Of that, $65 million came from the state, $30 million from private donors and $2 million from other sources, according to Marti Brick, the university director of external affairs. The university spent an additional $8 million on new equipment.

Cornell's project, expected to be completed next spring, focuses on remaking teaching and learning spaces, including classrooms and lecture halls, the library, cafeteria and public gathering spots for presentations. The project cost is $91 million (up from an original estimate of $66 million), according to campus spokeswoman Melissa Osgood. She said it is funded 90 percent by various state sources and 10 percent by the college.

In its written statement, UC Davis said its project has a greater and different scope.

“It is more than UGA's project and completely different than Cornell's project,” the statement reads. “The costs of planning, materials, construction and labor union participation (Georgia is a 'right to work' state) in three different states in three different parts of the country are not comparable.”

Nonetheless, some observers in the veterinary community say it's unconscionable to direct so much money to construction rather than to making education more affordable.

“I don't know how these deans of colleges can ... look those students in the eye as they are spending massive amounts of money on their colleges,” Dr. Carl Darby commented in the VIN message-board discussion. A private practitioner in upstate New York, Darby graduated from veterinary school at Cambridge University in 1991.

“At best, it seems like UCD is incredibly tone deaf to what its alumni are dealing with," he continued, "and at worst, it is an example of extreme fiscal irresponsibility at a time [when] reducing ... tuition is supposedly a major concern for deans and colleges.”

Dr. Ned Jackson, a 1995 UC Davis alumnus, shares the concern. “Student debt is probably the biggest single crisis our industry has ever faced,” he said in an interview by email. “People have to change their priorities. Having students go into a near lifetime of debt just to go to school in a fancy facility is ludicrous.”

The average educational debt of 2016 veterinary school graduates was $143,758 or $167,535, depending on how the figure is calculated. More than 20 percent of graduates last year had educational debt of $200,000 or more, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Meanwhile, starting salaries don't match the super-size debt. Mean income for graduates who obtained full-time employment before graduating was $73,380 in 2016, according to the 2017 AVMA Report on Veterinary Markets. The Bureau of Labor Statistics put median pay among all veterinarians employed in the United States at $88,770 in 2016.

To those critical of prioritizing new buildings over the high cost of education, UC Davis veterinary school officials say that the proposition is not either-or. For example, raising donations for facilities and scholarships are not mutually exclusive, they said: “During our campaign we anticipate that we will expand our interest in scholarships, as many donors we contact may choose to donate to our students versus a building."

The statement continues: “We have more than doubled our scholarships for our students over the past five years, and the costs of tuition and fees have been held in check over this same time period.”

In 2016, the school provided $2.7 million in scholarships, $500 to each first-year student for computer support and $4 million more in financial aid, the statement notes. (Financial aid typically consists of loans and grants.)

For California residents, UC Davis ranks 4th most affordable among 35 veterinary programs in the United States, Canada and Caribbean, according to data compiled by the VIN Foundation.

“UC Davis does a better job than most schools right now keeping costs down relative to the ranges we see elsewhere,” said Dr. Anthony Bartels, VIN's debt-education director. But, he suggested, it might do better still if it put as much energy into soliciting donations for scholarships as for facilities.

“They've already raised $57 million in less than two years without a public effort. So scholarships represent 5 percent of what they raised in two years for facilities upgrades without a public campaign,” Bartels said. “ ... Just imagine if a similar effort went into scholarships.”