Photo by Dr. Jeffrey Stott

Dr. Myra Blanchard, a specialist in immunology, pathology and microbiology at UC Davis, spent more than a decade trying to pinpoint the cause of epizootic bovine abortion. In 2005, she and fellow researchers cracked the case. They've since developed a vaccine and have inoculated more than 10,000 heifers in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, where the disease is prevalent.

Beef cows grazing on spring grasses of the Sierra Nevada are at the center of a 50-year battle between science and nature.

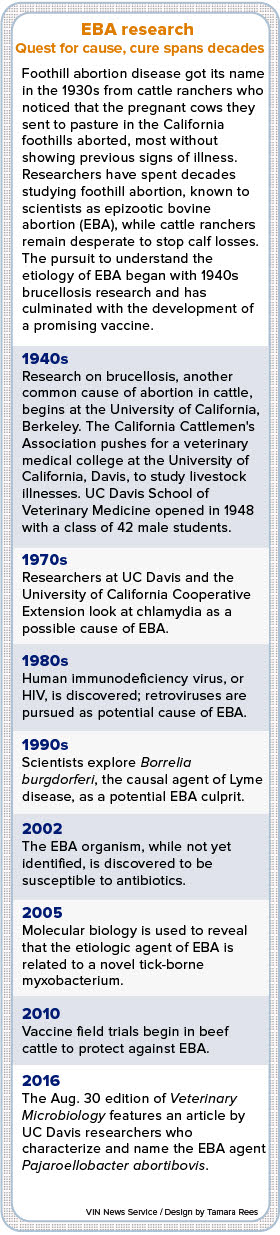

The saga involves epizootic bovine abortion (EBA), commonly known as foothill abortion disease. Its annual emergence throughout the foothills of southern California, Nevada and Oregon prompted the birth of a veterinary school, united scientists and ranchers and introduced practitioners to a strange tick and novel pathogen.

Now, development of a vaccine by researchers at the University of California, Davis, could one day erase EBA from the foothills, where the disease has caused devastating economic losses since the 1930s, when ranchers first reported the "abortion storms" they were witnessing.

Dr. Tom Talbot, a veterinarian and past president of the California Cattlemen's Association, saw it firsthand 45 years ago, when his father ran heifers into the foothills near Bakersfield. "We brought them back to our area to calve," he recalled. "They aborted maybe 90 percent."

EBA-related fetal losses today cost the beef industry $6 million a year, he estimates.

Researchers are working to change that. Dr. Jeff Stott, a professor of pathology, microbiology and immunology at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, is among them, leading a team of scientists on a quest to crack mysteries of EBA that have stumped medical professionals for a half-century. Among his major successes is the discovery in 2002 that EBA could be tamed by antibiotics. Most recently, the bacterium that causes the condition was isolated and named Pajarellobacter abortibovis. The designation reflects its host, a parasite native to California hill country called the pajaroello tick.

That finding marks the latest in efforts to lift the veil on a mysterious disease and eradicate it. Dr. Bennie Osburn, dean emeritus of UC Davis's veterinary school, is among those who studied foothill abortion disease in an attempt to find its cause. At age 79, Osburn has a long perspective, dating to the 1940s, when researchers believed that Brucella abortus, the same brucellosis strain common among dairy cattle, might be the culprit.

"I am probably one of the few still around to hear the story from some of our forefathers," Osburn said by email.

The quest to tackle foothill abortion began after World War II, when Drs. Hugh Cameron and Margaret Myers embarked on a journey to study brucellosis. Although they were on the wrong track toward unraveling EBA, their research advanced the veterinary profession's knowledge of brucellosis, a contagious bacterial disease in livestock that also infects humans. "They were involved in classification of Brucella spp. isolates from different animal species and some vaccine work," Osburn said. "Their efforts were of significant importance to the understanding of Brucella spp. but did not abate the abortions which were occurring in California."

Frustrated cattlemen in the area had organized and lobbied the state legislature to open a veterinary medical program in California to address animal diseases and the heavy abortion rate in beef cattle. At the time, the closest veterinary medical college was in Washington, where "there was little or no interest in livestock diseases relevant to California," Osburn said. "These arguments helped carry the day in the legislature for a veterinary school being established at Davis."

Thus, the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine was born. The program welcomed its inaugural class in 1948.

It would take nearly seven more decades, however, to crack EBA.

Among the first to make significant contributions in the study of foothill abortion were Dr. Jack Howarth, a clinical professor, and veterinary pathologist Dr. Jack Moulton. During the early 1950s, the team performed a necropsy on an aborted fetus that showed unusual lesions in the fetal organs and identified them as characteristic of the disease, Osburn recalled. Several years later, Dr. Harvey Olander, then a graduate student, collected tissue samples from the fetuses of affected cattle and defined their unique pathological features. Dr. Peter Kennedy followed up by characterizing the disease based on the lesions.

Osburn joined the UC Davis staff in the 1970s, after earning a doctorate in comparative pathology. "I, along with Dr. Kennedy, found that these fetuses had a demonstrable immunological response based on gamma globulin levels in fetal serum, but we were unable to associate it with any particular agent," he said.

In other words, elevated antibody levels in the fetuses' blood showed their immune systems were fighting a pathogen. But scientists hadn't identified it.

When Stott arrived at UC Davis in 1977, researchers were focused on a strain of chlamydia that’s known to cause abortion and reproductive diseases in animals.

But trials of a chlamydia vaccine failed to protect cattle from foothill abortion. Some researchers gave up their search. Others, however, emerged with interest and a fresh perspective. Drs. Ed Loomis and Ed Schmidtmann, both with the UC Cooperative Extension, were first to name the pajaroello tick as a potential disease vector.

Like almost everything else in this disease, the tick was an odd example of its kind. Talbot, the California Cattlemens Association official, worked for the UC Davis Veterinary Medicine Extension in the mid-'70s while a student at the veterinary school. He recalls bug-collecting in the foothills. "You go up in these areas and find an oak tree, take a pan with about a two-inch rim and bury it," he said. "Put a piece of dry ice in it, and the ground practically starts shaking. These little buggers come up out of the dirt."

Pajaroello ticks are nearly microscopic. "They aren't like any other tick. You wouldn't find them unless you were looking," Talbot said.

The disease agent, however, remained a mystery. The list of possible culprits reflected a Who's Who of pathological agents of the '80s and '90s.

"Retroviruses became in vogue in the '80s," Stott said. "When HIV came along, everyone here jumped on that. It was sexy, and folks wanted it to be an HIV-like virus."

Then Lyme disease emerged and researchers' focus turned to Borellia burgdorferi pathogen responsible for the tick-borne illness. Some believed it might also cause EBA. "That’s when I came on," Stott said.

Stott and UC Davis microbiologist Rance LeFebvre disproved the B. burgdorferi hypothesis at a time when many researchers had abandoned the quest for the EBA grail. Yet Stott and his colleague Dr. Myra Blanchard persisted.

There wasn't a lot of money to fund Stott's research, and it was slow. So he collaborated with scientists at the University of Nevada. "Combining our resources with those of UNR to pursue research on this disease made a lot of sense," Stott said. The team discovered that injecting heifers with thymus tissue from aborted calves could reproduce foothill abortion disease, yet they were unable to find an organism in the tissues.

Stott credits the eventual discovery of EBA's causative agent to 21st century technological advances. "It was molecular biology that was our savior," he said.

The microbiological search, Stott said, was frustrating. But they had determined that infected heifers could be successfully treated with antibiotics, proving that the causative agent was a bacterium rather than a virus. While most bacteria grow readily in culture, this one remained stubbornly elusive.

The break came around 2005, when Stott's postdoctoral fellow Donald King used molecular biology to identify the bug as being most closely related to a group of soil microbes called myxococcus.

"We were finally able to pull the gene out, and that told us it was a wild bacteria. It’s a myxococcus," Stott said. "Nobody in medicine knows what that means because there aren’t any other pathogenic myxococcal bacteria."

Collaboration with another research laboratory provided the key to propagating the mystery organism and isolating the bacterium.

That partnership took place inside UC Davis, where Dr. Stephen Barthold, director of the Center for Comparative Medicine, suggested trying to recreate the disease in his laboratory mice. "We injected ground thymus from the aborted fetuses into some immunodeficient mice," Stott said.

Stott had nearly forgotten about the mice when he was informed three months later that some were dying of wasting disease. "We opened them up and found a large spleen," he recalled. "This is a hallmark of foothill abortion in cattle fetuses. We ground up these enlarged spleens and injected them into additional immunodeficient mice and successfully transferred the wasting disease.

"After a few passages in mice, we put it into pregnant heifers, and wow, yuo want to talk foothill abortion — that was hot, hot, hot!" Stott said, still excited several years later. "We took samples from the aborted fetuses and put it back into mice and caused wasting disease again."

Richard Walker, a microbiologist at the Center for Animal Health and Food Safety, developed stains to view the bacteria on a slide. "... And there it was. It had been right in front of us all along!" Stott exclaimed. "We couldn't grow it in culture, and still can't today."

When the bacteria's DNA was found in the pajaroello tick in 2005, it confirmed the hypothesis that the parasite was the disease vector. Stott's team also proved the organism to be the cause of the disease by meeting all but one of Koch's postulates, four rules that scientists use to determine whether there's a causative relationship between a microbe and a disease.

Developed by scientists in the 1880s, Koch's postulates state that a microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from disease, but not in healthy organisms. The microorganism must cause disease when introduced to a healthy organism. And the microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

Finally, the microorganism must be cultured in pure form. While Stott didn't make that happen, he said the organism's purity was established using molecular biology tools that probed its genetics.

This opened the door to creating a vaccine.

"Everyone got in line to help," Stott said. The Center for Veterinary Biologics, a division of USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, got involved, as did the California Cattlemen's Association, which is sponsoring some of the research.

The vaccine is on its seventh year of field trials. The response from Western cattle ranchers, Stott said, is "overwhelming."

"When California Cattlemen's Association put out a newsletter containing an application form to enroll in experimental vaccine trials, we got a huge response," Stott said. "We are now up over 10,000 heifers in trials. And the paperwork for the ranchers is substantial. That level of involvement tells me how bad the problem is."

UC Davis is working with an unnamed pharmaceutical company to develop a commercial version of the vaccine, expected to become available within two years.

Talbot anticipates high demand from ranchers even though handling the vaccine isn't easy. It must be transported in liquid nitrogen. Heifers must be vaccinated 60 to 90 days before being bred. So far, the vaccine appears to provide long-term immunity.

Talbot reflects on the many researchers who aimed to solve the foothill abortion mystery, believing it could be the highlight of their careers. Most now are dead.

"It's pretty amazing to think about a disease with that significant an impact and all the years of research that have gone into it," he said.

If the vaccine ends the scourge of EBA in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, it will be thanks to the efforts of generations of committed people, Stott said.

"After a career in academia, I can look back and say this is probably the most amazing example of an effective collaborative effort you could find," he said. "I take great pride in the collaboration we were able to develop over the years. It all paid off in the end."

Osburn refers to the journey as "an amazing 50-plus-year adventure."

"Now we hope this does not mean that the veterinary school has done its due diligence and now can be closed," he laughed.