Photo by Julie Deherrera

To compensate for hearing loss, Dr. Kent Littlehale uses an electronic stethoscope in combination with over-the-ear headphones and hearing aids to auscultate patients. A standard headset cord connects the headset to the stethoscope.

After more than 30 years spent in the company of barking dogs and screaming birds, Dr. Kent Littlehale describes his hearing loss as “pretty profound.”

The veterinarian in Saratoga, California, finally started wearing hearing aids at work, only to find that they introduced another problem: Hearing aids are incompatible with standard stethoscopes.

Littlehale shared his plight recently on a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, where he encountered colleagues in the same situation.

“Pulling hearing aids out to use a standard stethoscope is totally impractical (not to mention that you are dramatically increasing the risk of losing a very expensive and small device!),” Littlehale wrote.

His solution: Using an electronic stethoscope with over-the-ear headphones in conjunction with the hearing aids. Electronic stethoscopes aren't as convenient as standard stethoscopes but are a decent alternative, he said.

“So besides my reading glasses perched on my forehead and my bulky hi-tech stethoscope, I look the same as I did when I graduated in '83. NOT!” he quipped.

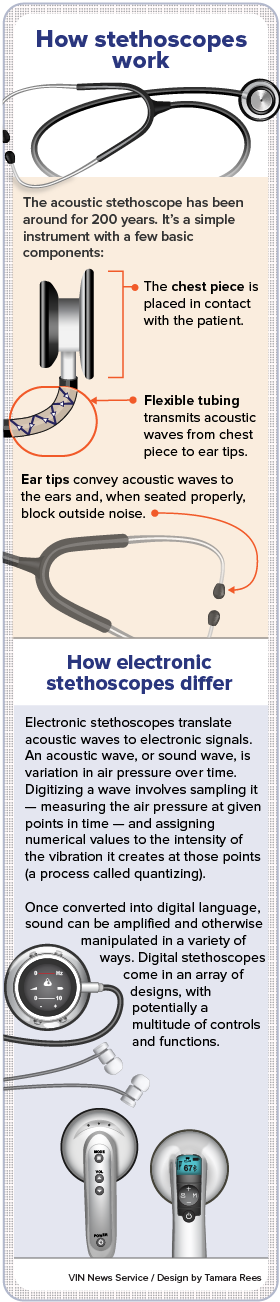

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the acoustic stethoscope, proving its durability as a fundamental medical diagnostic tool. But as Littlehale and other doctors with hearing loss attest, conventional stethoscopes may not sufficiently amplify a sick patient’s clicks, whooshes, wheezes and gurgling. Where classic stethoscopes fail, electronic stethoscopes can further amplify sounds, even recording them to a smartphone or tablet to be analyzed in real time by a computer program.

Electronic stethoscopes became available in the mid-1990s. They’re more complicated and pricier than their acoustic counterparts. They require batteries and cost about $400 to $500, compared with $100 to $200 for regular stethoscopes.

Clive Smith, CEO of Thinklabs, an electronic-stethoscope maker in Centennial, Colorado, set out to redesign the tool in the late 1980s, after reading in a journal article that conventional stethoscopes hadn't improved much since they were invented in 1816. Physicians, he said, confirmed that even top-of-the-line stethoscopes did a poor job of amplifying heart and lung sounds, so he designed a digital version.

“Wires transmit more faithfully than tubes, so we eliminate the tubing and transmit electronically all the way to the listener's ears,” Smith said. “This is beneficial to all users, whether hearing-impaired or not.”

Today, there are about 10 brands of electronic stethoscopes on the market made by companies including Littmann, American Diagnostics Corp., Cardionics and MABIS.

Not all electronic stethoscopes are designed with hearing loss in mind, according to Samuel Atcherson, director of the Auditory Electrophysiology and (Re)habilitation Laboratory at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Some models include noise-cancellation. Some combine amplification and noise reduction. Some offer only amplification. Some provide visual recordings.

How to choose?

Figuring out what works for an individual may take some experimentation, said Dr. Kimberly Dodge, a former board member of the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Loss (AMPHL).

“I’ve seen everything from special holes created in hearing-aid ear molds that will allow steth earpieces to fit into them, to using the newer Bluetooth FM systems rigged up to an electronic stethoscope so that the sounds are transmitted [wirelessly] to the hearing aid,” said Dodge, who has been deaf since age 8. “You may need to play around a little bit to find out what works for you.”

Atcherson agreed. “For those with hearing loss … there will be a great deal of variation [in] who selects what, why and for what purpose,” he said. Atcherson was diagnosed with hearing loss at age 3. He has cochlear implants, electronic devices that replace the function of the damaged inner ear.

Atcherson said hearing aids and implant devices work poorly with conventional stethoscopes because their receivers are designed to capture the sounds of speech, not body functions.

Dr. Steve Bohn learned that the hard way.

The 64-year-old veterinarian in Gualala, California, initially thought that wearing hearing aids that sit in the ear canal would work well with a stethoscope; he reasoned that the hearing aid would augment the sound transmitted by the stethoscope. Instead, he discovered that “it was painful and … didn’t work at all.”

Bohn then tried a hearing aid that sits over the back of the ear. Still no good. It increased background noises such as conversation and the whir of fans.

Finally, Bohn switched to an electronic stethoscope. The electronic version does a better job amplifying body sounds, he said, although background noise picked up by the hearing aids remains an issue. “You can still hear the heart, etc.,” he said. “It is just annoying.”

Even for those without diagnosed hearing loss, electronic stethoscopes may have appeal.

Dr. Kenton Flaig of Portville, New York, does not wear hearing aids nor has his hearing been tested. He switched to an electronic stethoscope after he began having trouble hearing a heart beat using a conventional stethoscope.

“Sometimes I get a plugged ear,” Flaig said, “or maybe I'm going deaf and don't know it. I got that scope, and it was better.”

The electronic instrument can’t take as much punishment as its old-fashioned counterpart, though. Flaig noted, “Dropping it on a hard tile floor may kill it.”

Veterinarians experiencing hearing loss and needing guidance can turn to Dr. Danielle Rastetter for help. She is the veterinary representative at AMPHL, an all-volunteer nonprofit group that she helped found.

Rastetter began using hearing aids at age 3 due to a congenital condition that worsened over time. She now has cochlear implants and uses an amplified stethoscope that plugs into them. Her particular implants aren’t compatible with Bluetooth technology but, she said, newer ones are.

Then there are non-technological adaptations. Rastetter knows some completely deaf veterinarians who don't use any digital equipment whatsoever.

“Using your hands, you can actually pick up [heart] murmurs once your hands are trained,” Rastetter said. “… Some go by vibrations. I know an equine vet who puts her face on the chest.”