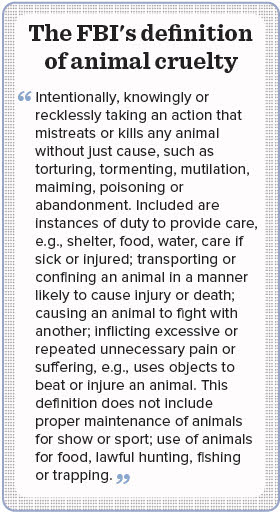

Sexual abuse of animals and other forms of cruelty are on the FBI's radar.

By next January, law enforcement agencies will be able to log and track instances of animal cruelty via the FBI's National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS), a database used by investigators across the country to record and aggregate reports of criminal activity. FBI spokesman Stephen Fischer explained that including animal abuse in NIBRS' list of crimes means that everything from dog fighting to bestiality now will be a NIBRS category.

Animal welfare concerns aside, tracking animal cruelty is important, experts say, because those who engage in it are apt to commit crimes against people. Even so, bestiality remains legal in several states including Vermont, where a bill to ban bestiality is in the works. Supporters of the measure contend that 20 percent of children who sexually abuse other children first abused animals. Among juveniles who engage in sex with animals, 96 percent admit also to sexually abusing people and report more offenses than other sexual offenders of their same age and race. The FBI found high rates of sexual assault of animals in the backgrounds of serial sexual homicide predators.

Sexual abuse of animals used to be covered under sodomy laws, but many of those laws have been repealed since the 1950s in order to keep up with modern views about sexual practices between consenting adults. Not all states realized that repealing sodomy laws would leave bestiality a legal practice. A tagline on the Vermont legislation's talking points speaks to the topic's taboo nature: "We don't need to talk about it. We just need to outlaw it."

Much as polite society may wish not to acknowledge it, bestiality exists. An Internet search for bestiality brings up recent arrests, where to find it, chat rooms, videos, tourist advertisements and so on. Old sayings such as, "Ah (fill in location), where the men are men and the sheep are nervous" indicate that sexual relations between people and animals are neither new nor rare.

Veterinarians in the United Kingdom randomly were polled for a study on non-accidental injury in small animals, which appeared in the July 2001 issue of the Journal of Small Animal Practitioners. Based on the responses, 6 percent of 448 cases of non-accidental injury reported were identified as sexual in nature.

In a 2006 commentary in The Veterinary Journal, veterinarian and abuse expert Dr. Helen Munro wrote: "The impression is that many continue to think of bestiality as a farmyard activity involving animals sufficiently large enough not to be injured and therefore not much to worry about. It seems that even in these modern times, the sexual abuse of animals is almost a last taboo, even to the veterinary profession."

Signs of sexual abuse

Dr. Martha-Smith Blackmore is trying to change that. The vice president of animal welfare for the Animal Rescue League of Boston and a sometime expert witness in court cases involving animal sexual abuse, Smith-Blackmore gives presentations on the subject to veterinarians in which she discusses ethical and animal-welfare considerations.

Bestiality is most commonly found among violent offenders, sex offenders and the sexually abused, she said, and perpetrators may demonstrate a failure to relate to people. There isn’t much data on this topic because it has been so taboo to research, but, she said, perpetrators are more likely to have been victims of emotional neglect and abuse as children.

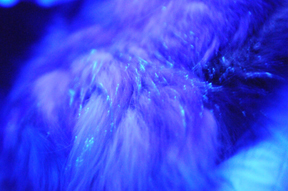

Photo courtesy of Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore

A Wood's lamp examination uses transillumination to detect bodily fluids. Semen in this dog's fur fluoresces under ultraviolet light.

Smith-Blackmore points out that sexually abused animals might exhibit behavioral changes rather than physical injuries. Depending on local laws, proving genital contact between humans and animals is enough evidence to determine an animal has been sexually abused. Laws in other jurisdictions require that physical harm be evident.

She believes all veterinarians should receive training on how to identify when an animal has been sexually abused, which can be difficult, especially if the animal is examined too long after the alleged incident.

The signs, Smith-Blackmore said, can be overt or subtle:

- loss of fur, abrasions or tears around the perineum, vaginal canal or rectum

- peritonitis (inflammation of the abdominal lining)

- bodily fluids that fluoresce under ultraviolet light

- injuries to the anus, nipples or genitalia

- recurrent vaginitis, proctitis or urinary infection

- free gas in the uterus or vagina

- unusual meekness in an animal

- foreign objects within the genitourinary tract

Smith-Blackmore recommends that veterinarians learn how to use a rape kit, the same kind issued to human hospitals.

"The official kit has the state logo and other information on the box, and a tracking form," she said. "The reason I try to use those is to send a message to the court that this is a sexual-assault case. The way it's packaged and presented is the same as assaults against people."

Survey radiographs can help record co-morbid injuries or subclinical findings, Smith-Blackmore said. Radiographs should be dated and include the animal's identifying information. Radiographs should be interpreted by a board-certified radiologist, she added.

Bestiality carries human health risks, too. Animals can carry human sexually transmitted diseases, bacterial or parasitic infections of the genital, intestinal or urinary tract as well as cancer-causing viruses such as human papillomaviruses.

Sexual perversions are not necessarily considered psychiatric disorders, Smith-Blackmore said. The current edition of "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders," or DSM, says a paraphilic disorder (paraphilias are conditions marked by sexual attraction for objects or people outside the norm) must cause that person or another person harm.

“In the most recent edition, DSM did not categorize bestiality as a perversion because it was decided that harm to animals is not causing someone harm,” Smith-Blackmore said. “They are human-psychology-centric. It may have been an editorial philosophy.”

Evidence

Animals targeted come in all sizes. In a 2010 raid on a farm in Whatcom County, Washington, found to be promoting bestiality, 13 mice were euthanized after being found with their tails cut off and string tied around their bodies, which were slathered in petroleum jelly. Horses and dogs were removed from the premises by the local humane society.

Animal sex farms, which draw customers willing to pay for such activity, exist in many other countries including Denmark, where an underground market reportedly has flourished in response to bestiality bans recently imposed in Norway, Germany and Sweden.

Sexual contact with animals is banned throughout most of the United States except: Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Kentucky, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Vermont, Washington, D.C., West Virginia and Wyoming, according to a listing compiled in 2014 by Michigan State University's Animal Legal & Historical Center.

"Regardless of the philosophical platform from which one views the activity, bestiality is criminally sanctioned in a majority of states," the Animal Legal & Historical Center said. "Even if a state does not specifically proscribe the activity, it may be covered under other aspects of a state’s sex crimes code or even a broader animal cruelty law."

It takes just one highly publicized case to bring bestiality to the forefront of public consciousness.

In 2005, Seattle family man Kenneth Pinyan died of peritonitis from a perforated colon after having anal sex with a stallion. His case became national news because he didn't want to go to the hospital for fear of losing his security clearance at work, even though his actions were not illegal in Washington at the time. He was dropped off anonymously at the hospital, dead on arrival, by James Tait, who recorded the act and later disseminated video footage of it online. Washington authorities said that Tait helped run an animal sex farm advertised online as a tourist destination. The owners of the horses and barn were upset to learn that people were sneaking into the stalls to have sex with their horses.

The incident was widely reported because of its notoriety, prompting Washington lawmakers to make bestiality a felony crime in 2006. The incident was recounted in a documentary that debuted at the 2007 Sundance Film Festival.

Tait went on to run a similar animal sex farm in Tennessee. Numerous video recordings were discovered showing people having sex with animals housed there. When Tait admitted to having sex with ponies and other animals, a law enforcement official expressed relief that the case was over. "It has brought a lot of embarrassment and humiliation to the community and this town," Maury County Detective Sgt. Terry Chandler told a news agency.

Lawmakers appear to be just as uncomfortable, at least in Vermont, where Joanne Bourbeau said the sexual abuse of animals is more common than most realize.

Bourbeau, director of the Humane Society of the United States' northeastern region, is a founding member of the Vermont Animal Cruelty Response Coalition. She refers to animals as "perfect victims" because they can't speak up about their injuries.

That silence along with legislators' reluctance to have their names associated with a bestiality bill have thwarted efforts to explicitly outlaw having sex with animals in Vermont, she said.

"The public and lawmakers are so uncomfortable, they don't want to discuss it,” Bourbeau said. "Animal-cruelty laws don't necessarily cover (bestiality) unless the animal sustains physical injuries, so you can't necessarily make a case for it. In some states, livestock are exempt from animal-abuse laws. In some cases they can only charge lewd and lascivious behavior if it's done in public.”

Bourbeau pointed out that online bestiality chat rooms originate in almost every state. "New Jersey had a bill pending," she said. "You'd think it would be a no-brainer, but it isn't."

Despite politicians' reluctance to address the subject, Bourbeau plans to continue her fight in Vermont to criminalize bestiality. She's optimistic.

"Animals are gaining more protection because people see them as family members," she said.