Catch up on an ER venture, insect proteins, a pioneering training program and rabbits

REVS_vets

Photo by Michelle Gabel

Drs. Bruce Ingersoll, Brenda Buck and Dori Marion were photographed with furry friends one month before they launched a nonprofit service offering after-hours veterinary care in Rochester, New York. The trio's venture has proven successful so far.

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

As another year comes to a close, the VIN News Service revisits some notable stories from the recent and not-so-recent past. Read on to learn what happened when three practitioners in upstate New York decided to fill an emergency care void in their off-hours. Find out where insects are showing up as an ingredient in pet food. Learn how an innovative veterinary vocational program is growing. And catch up on the spread of a lethal rabbit disease in North America.

Rochester's fledgling emergency service digs in

When a trio of Rochester, New York, general practitioners volunteered in November 2023 to step into the gap left by the closure of the city's only veterinary emergency hospital, it was an ambitious undertaking.

But Drs. Brenda Buck, Bruce Ingersoll and Dori Marion lived up to their pledge. Just over a year later, Rochester Emergency Veterinary Services (REVS) is a booming nonprofit with plans to grow and expand.

Practitioners at REVS began in February to see patients after hours on weekdays and continuously over the weekend at the Animal Hospital of Rochester, which is Buck's practice. In its first few months, Ingersoll worked most night shifts, and Buck covered many weekends and monitored patients Monday through Friday.

"It was and is really challenging," said Marion, who is the chairman of the nonprofit's board. "But the community at large has just been phenomenal. Everybody has been really appreciative and patient. I think that's what's kept us going."

In its first 10 months, REVS treated more than 8,000 patients and hired and trained 63 employees, including seven full-time veterinarians, according to the practice founders. It also raised more than $1.5 million in donations and was awarded multiple grants.

"We've learned that operating as a nonprofit comes with unique complexities, and much of our growth has involved learning through experience," Marion said.

Demand consistently has been high, but the number of patients REVS can handle is constrained by two main factors: the limited number of veterinarians on staff and a lack of space at the current location.

"Finding veterinarians willing to work emergency hours has been an ongoing challenge," Marion said, adding that once the hospital offers round-the-clock care, there will be more attractive shifts in the mix.

REVS plans to move early next year into a 25,000-square-foot repurposed dialysis center in East Rochester. "This expansion will allow us to operate 24/7, significantly increase our capacity, elevate the level of medical care we provide and broaden our range of services," Marion said.

With the move, the founders take an important step toward another ambitious goal: creating a nonprofit emergency and specialty hospital in the mold of Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston and Schwarzman Animal Medical Center in New York City.

— Lisa Wogan

A slow creep: Insects appearing on more pet menus

Insects are the most common animal on the planet, found just about everywhere — including, now, as ingredients in processed pet food.

Dogs, cats and other animals have long gobbled on the odd bug unfortunate enough to cross their paths. Over the past decade, though, dried and ground insects have been gradually appearing in pet bowls, as governments and companies see their potential as a viable source of nutrition that's kinder to the environment than traditional protein sources like beef and pork.

In March 2020, the VIN News Service reported that a British company, Yora, was selling a dog kibble in Europe containing the larvae of black soldier flies. At the time, insect ingredients hadn't been officially approved for pets across the Atlantic. Much has changed since then.

In 2021, the Association of American Feed Control Officials, a standard-setter for ingredients in animal food in the United States, approved the use of black soldier fly larvae in dog food. This year, AAFCO approved its use in cat food, too, and also approved the use of mealworms (beetle larvae) and crickets in dog food.

Yora expanded into the U.S. last year, where it's now making dog kibble at a factory in Ohio, tapping a local insect protein producer, EnviroFlight. Yora has added to its offerings a cat food, which it plans to launch in the U.S. soon.

Other notable players in the field include France's Ÿnsect, which announced in January that AAFCO had given it the first-ever authorization in the U.S. for the sale of mealworm proteins (derived from larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor) in dog food.

According to a study published last year in the Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 43 insect-based pet food brands existed worldwide at the time, 35 of them in Europe, where the market has been "growing rapidly" since Yora started selling its products there in 2015. "Recent regulatory approval in the U.S. will push this growth in the North American market, too," the researchers predicted.

Big players like Mars Inc. and Nestlé Purina have wet their toes but haven't dived in. In 2021, Mars launched an insect-based cat food called Lovebug in the U.K. Mars confirmed to VIN News that it hasn't introduced that product or any other insect-containing pet food anywhere else.

Nestlé Purina started selling an insect-based pet food for dogs and cats in August 2023 exclusively in Switzerland. The launch was a pilot, and "the results were encouraging," the company told VIN News, although the product no longer is on the market. Nestlé Purina cited competitive reasons for not commenting on whether it has any similar product coming.

— Ross Kelly

High school veterinary program to expand

Since its founding 12 years ago, a community clinic that's the hub of a pioneering high school vocational program in veterinary medicine has been operating out of a 2,200-square-foot space once occupied by two regular classrooms.

There, the nonprofit program called Tufts at Tech in central Massachusetts has been at capacity for years, handling 5,500 cases annually, according to its director.

Today, the program's partners — Tufts University's Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine and Worcester Technical High School — are looking forward to a major expansion.

A donation of $2.5 million from the Worcester-based George I. Alden Trust and a pledge by the Cummings school to fundraise another $2.5 million is enabling the clinic to be expanded and outfitted in a 8,500-square-foot space, nearly quadrupling the existing facility's size.

"This is a great thing for the high school, the community, veterinary students and the [veterinary] school," said Dr. Greg Wolfus, noting that every Cummings student spends four weeks of their clinical training there. The veterinary students' work examining, diagnosing and treating patients is overseen by four full- and part-time faculty members. Veterinarians from the community also volunteer at the clinic.

The Worcester Tech students are taught veterinary assistant skills. Since its inception, 175 students have graduated; 55 students are in the program now. Among alumni, two have become veterinarians and three are in veterinary school, Wolfus said. While the high school doesn't track all the program graduates, it's aware of at least two who have gone on to work as veterinary assistants and one as a veterinary technician.

The clinic provides significantly discounted services — priced at 25% of the national average — to income-eligible residents. Eligible individuals are those who qualify for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or the Women, Infants and Children program; are Worcester Housing Authority residents; or are families of Worcester Tech students. Pet owners must show proof of qualification at every appointment and attest that the animal needing care is theirs.

Wolfus said the 5,500-per-year clinic caseload reflects services to only a small portion of the 31,000 families in the region believed to qualify.

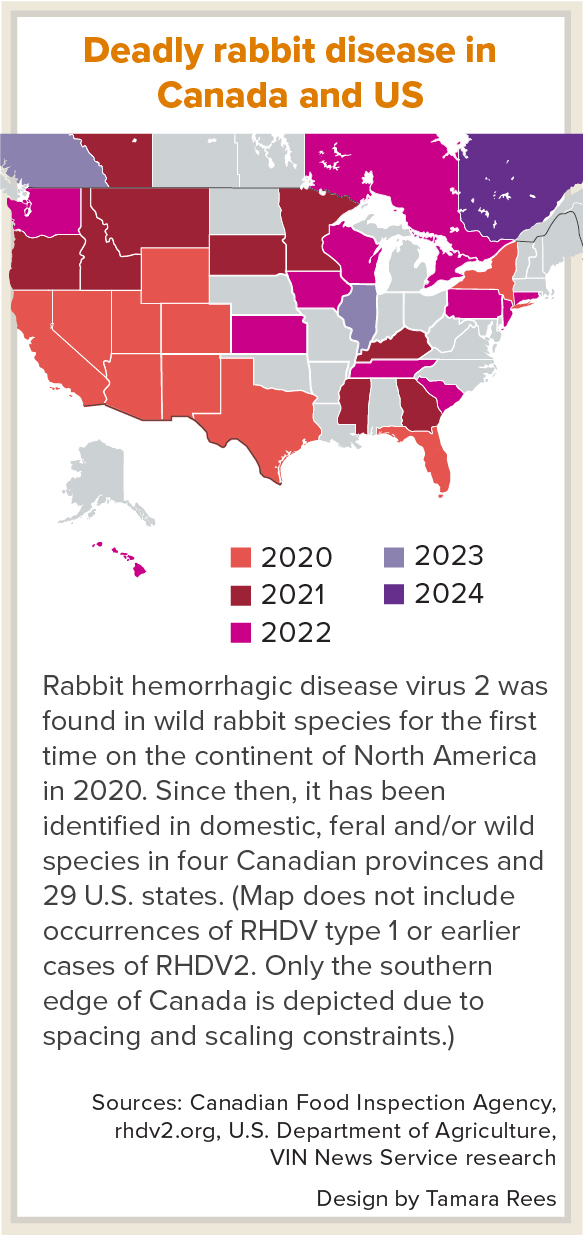

rabbit virus map

In addition to providing services including vaccinations, spaying and castrations, dental care and urgent care for conditions such as ear infections, vomiting and diarrhea and upper respiratory infections, the clinic has added behavior training for owners of new puppies. It also offers counseling by a veterinary social worker to clients, veterinary students and participating high school students when needed for difficult situations, such as euthanasias.

The community clinic inspired the establishment of at least three similar clinics elsewhere in the state. One of them, Angell at Nashoba, closed in July 2023 after seven years in operation, owing to the rising cost of staffing and supplies in combination with limited space, according to an Angell spokesperson. Another school-based community clinic run by the organization, called Angell at Essex, remains open.

Wolfus anticipates Tufts at Tech's expansion will be completed in late 2026.

— Edie Lau

Lethal rabbit disease continues advance in Canada and US

In the nearly five years since a highly contagious viral disease that causes sudden death in rabbits was first identified in wild jackrabbits and cottontails on the continent of North America, the virus has expanded its footprint. Since March 2020, rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2) has been confirmed in 29 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces.

RHDV2 causes lesions throughout a rabbit's internal organs and tissues, particularly the liver, lungs and heart, resulting in bleeding. It is often fatal. The virus does not make humans sick.

The pathogen is now considered endemic in much of the western U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, showing up in domestic and wild or feral species in 14 states. In the Midwest and on the East Coast, cases have been limited to domestic rabbits.

The number of affected provinces in Canada doubled in the past two years, with confirmed cases in feral rabbits in British Columbia in 2023 and a domestic rabbit in Quebec in 2024.

In the mountain town of Canmore, Alberta, RHDV2 reportedly wiped out the feral rabbit population.

As of December 2020, Mexico had identified RHDV2 in 19 states. Authorities in the country could not provide updated information by press time.

— Lisa Wogan