Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

revised final art element

To read the North American pet insurance trade group's latest state of the industry report, one might think all is well: More dogs and cats are covered each year and sales revenue continues to trend upward.

At least three veterinarians who have followed the industry for years have a different view. They see a business that, after four decades in place, has yet to find its footing and may, in fact, be slipping.

While 6.25 million dogs and cats are insured in the United States and Canada, the proportion of pets covered remains stubbornly low, between 3 and 4%.

Pointing to the meager share of takers, Dr. Kent Kruse declared, "Pet insurance is definitely a failure." The assessment comes from someone who spent nearly 20 years in the industry, starting with Veterinary Pet Insurance, the first company in the U.S. to sell coverage for veterinary care.

Another former champion of the industry, Dr. Doug Kenney, used similar terms to express his exasperation. "Any other industry that has been around for 40 years and has a 3% market penetration would be considered an abysmal failure," said the retired practitioner and pet insurance blogger and podcaster.

Dr. Frances Wilkerson, who's maintained an independent online guide to pet insurance since 2009, agrees, although as a consumer advocate, what bothers her more than the small share of takers are sharply rising premiums.

The North American Pet Health Insurance Association counters the gloomy take. "Overall, the industry has experienced roughly a four-fold increase in penetration over a handful of years, which is significant for a non-compulsory (or voluntary) insurance product," the group's executive director, Kristen Lynch, said by email.

It's not only veterinarians who have doubts about the pet insurance market, though. The Society of Actuaries recently hosted a webinar for its members, "Pros and Cons of the Current State of Pet Health Insurance."

One presenter was Laura Bennett, co-founder of Embrace Pet Insurance, which has operated for nearly 20 years. Now an independent consultant, Bennett says bluntly: "It is the type of business that I always tell people don't get into. It is hard to make money in the pet insurance business! Pet insurance is much more complex than you realize."

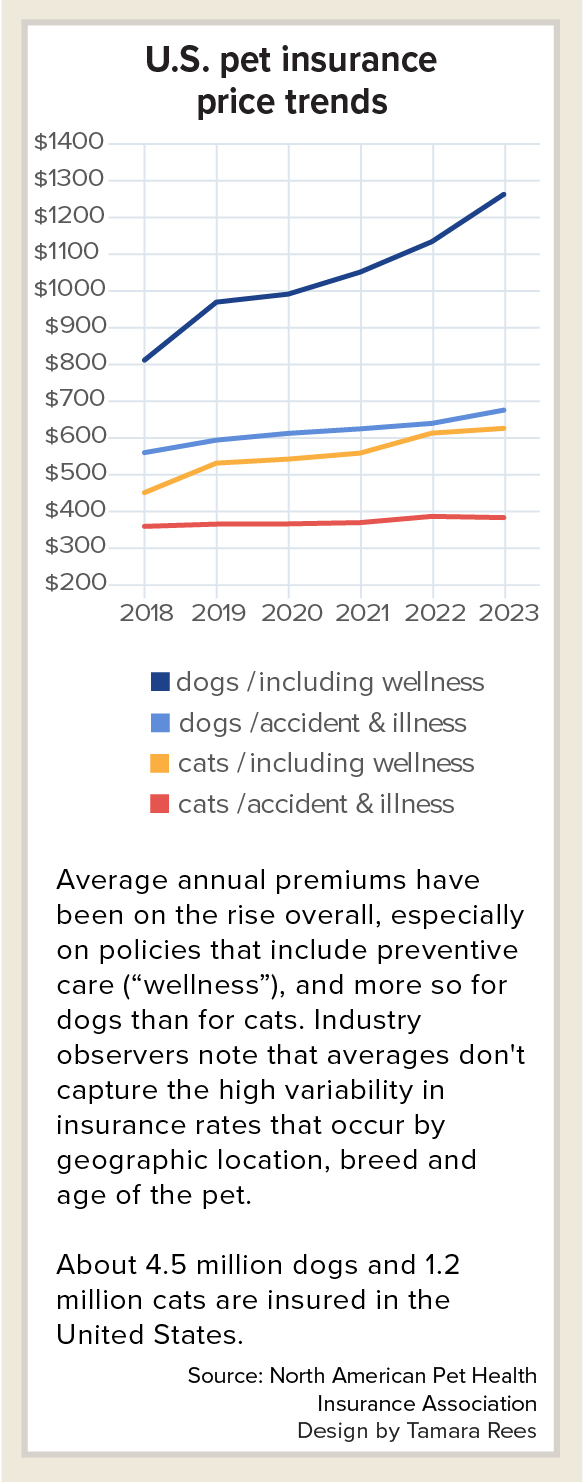

The sector has drawn negative headlines in recent years for sharply rising premiums. According to NAPHIA, the average annual premium rise was 11.4% between 2022 and 2023 for U.S. dogs that had policies including coverage for preventive care and 5.6% for U.S. dogs covered for accidents and illness only.

In Canada, dog policy increases during the same period were steeper: 13.5% for the broader "wellness" coverage and 15.6% for accident and illness. For cats, increases in both categories also were in the double digits.

The averages — which are weighted by factors that NAPHIA keeps confidential — can be misleading because they mask what insiders say are large disparities in premiums caused by variables such as geographic region, breed and age of the pet. Anecdotally, individual policyholders have reported much greater percentage increases than NAPHIA's reported averages.

No coverage at any price?

Deeper troubles in the domestic pet insurance market came into public view in mid-June when Nationwide, regarded as the largest pet insurer in the country with 1.2 million animals covered, disclosed that it would shed 100,000 policies over the next year.

In a statement, Nationwide said the nonrenewals are "not associated with the pet's age, breed or prior claims history." The company did not specify how it determined which policies to discontinue, citing only "inflation in the cost of veterinary care and other factors" for the "withdrawal of some products in some states." Asked by the VIN News Service for details, Nationwide only pointed back to its original statement.

Although 100,000 policies may sound like a lot, Lynch, the trade association executive, called it "a relatively small percentage of policies for an insurance category of this size."

That's little comfort to affected policyholders. Nationwide's action spurred the forming of a private Facebook group called Dropped by Nationwide Pet Insurance Whole Wellness? Join Us! that has drawn 1,500 members.

Veterinarians are seeing the impact on pet owners. Dr. Erika Im works at a Northern Virginia clinic where an estimated 10% of clients carry pet insurance. She's aware of two who have lost their Nationwide coverage. Each owns a cat, one age 11 and the other, 14. Both have chronic kidney disease.

The owners can afford ongoing management of the kidney disease, but Im said they and other pet owners probably would find it a stretch to pay out of pocket for major issues. "If a dog needs surgery for a serious condition like cancer, their total bill can be easily over $10,000 once costs such as the CT scan are counted," she said. "It's not something that somebody can easily pay."

Until recently, Im's opinion of pet insurance was neutral, based upon mixed experiences of her clients. "Some are satisfied with their coverage, while others are not," she said.

Then Im started hearing of clients whose premiums reached $500 to $600 per month as their pets entered middle to old age. That led her to question the advice she'd always given to clients — that if they were going to get insurance, they should do it when the pet is young. The guidance was based on what she thought was a compact between insurers and policyholders: Buy coverage for your pet when it's young and healthy, stick with it, and you'll be covered as the animal's health declines with age.

Regarding Nationwide, Im said, "It seems like this big pet insurance company has broken the basic promise of pet insurance, and it's ruining people's trust in the idea."

Bennett, the actuary and industry consultant, told VIN News that Nationwide's move was "a shock to the industry" that could taint all pet insurers. "People might be looking at the pet insurance industry as a whole and think, 'Is this how you do it? Why would I pay you money if, when I need you most, you won't be there?' "

While insurers generally have a right not to renew policies, Bennett noted, affected policyholders "can reach out to their state's insurance regulators and lodge a complaint."

An especially hard thing about being dropped from pet insurance is that unlike with automobiles, for instance, it can be impossible to obtain comparable coverage from another carrier. That's because pet health insurers do not cover pre-existing conditions. So a disease that developed after a pet was first covered by Nationwide would be a pre-existing condition to another insurer.

(Under federal law, health insurers for people must cover pre-existing conditions, but pet insurance is regulated as property and casualty insurance like home and automotive coverage.)

An online petition calls on Nationwide to allow affected policyholders to convert to other plans offered by the company. The petition has drawn nearly 1,000 signatures to date.

Trupanion, another large pet insurer, offers a unique window into how North American pet insurers are faring because it is listed on the stock market and, therefore, must disclose its full financial performance. Since listing in 2014, Trupanion has rapidly grown its sales revenue. But when factoring in expenses such as claims, Trupanion has yet to turn a profit.

Its CEO, Margi Tooth, said the lack of profit to date is the result of an intentional strategy. "It has always been our guiding mandate to maximize growth of insured pets in a market that is so underpenetrated," she told VIN News. "... [W]e have made a conscious decision to reinvest the money generated from our existing book of insured members to grow the category."

As for Nationwide's action, Tooth said Trupanion would not follow suit. "We have long made it clear to our members in our terms and conditions that we would not cancel their coverage under any circumstances other than for failure to pay their monthly premium or fraud," she said.

Inside pet insuring

One challenging aspect of insuring veterinary care is that the longer a given pet is covered, the more costly it becomes for the insurer, according to Bennett.

The reason is simply that the more time goes by, the greater the chance that the pet will need care resulting in a claim. Moreover, many policyholders who end up not filing claims because their pet is healthy tend to drop out, usually after the first year, resulting in an industry lapse rate of 20 to 30%, Bennett said. That leaves insurers paying claims on a population of generally less healthy animals, which pushes up premiums.

"If you had zero lapse rate, everyone's premiums would be lower," Bennett said.

Another driver of rising premiums is the cost of veterinary services, which is rising faster than inflation. The U.S. Consumer Price Index shows veterinary services went up 6.2% in the 12 months ending in July compared with 2.9% inflation across the index.

Factors behind veterinary inflation include rising pay for veterinarians and veterinary staff fueled by workforce shortages and new and enhanced treatments and diagnostics for companion animals, according to Bennett.

Then there's consolidation of veterinary practices by a particular segment of investor. "Prices go up when private equity comes in," she said. "They are in it to make money, so yes, they typically increase fees."

Private equity investors have been buying veterinary practices around the world for some years now. A big player is JAB Holding Co., a German investment firm that owns National Veterinary Associates, which has about 1,400 general and specialty practices in North America.

In 2022 and 2023, JAB went on a $4 billion-plus spending spree on pet insurers. Its portfolio now includes the North American brands AKC, ASPCA, Embrace, Felix, Figo, Hartville, PetPartners, Pets Best, Pets Plus Us, Pumpkin, Spot and 24PetProtect, as well as brands in Europe. The company's $4 billion expenditure exceeds what the U.S. market tallied in premiums revenue in 2023.

JAB's activities in the veterinary sphere have drawn the attention of U.S. senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, both Democrats. They sent a letter this month to JAB executives outlining concerns about the company's market power and requesting answers by Aug. 21 to a list of probing questions about its operations.

More popular abroad

In some countries, pet insurance is a more successful enterprise. It has the greatest reach in Sweden, where the country's largest pet insurer, Agria, says 92% of dogs, 75% of horses and 50% of cats are covered. Pet insurance has been available in Sweden since 1924.

The product also is relatively popular in the United Kingdom. Bennett, who grew up in England and worked in Canada and Ireland before settling in the U.S., said an estimated 30% or so of pets are covered in the U.K. She believes a key factor is a more relaxed regulatory structure, whereby revising premiums and coverage options is easier.

By comparison, insurance in the United States is overseen by each state and the District of Columbia. "It's hard to ... be innovative when you have to do 51 versions of a product," Bennett said.

In the U.K., "The way they allow you to market your product is much more flexible," she said. "You can change the pricing on a product for the same dog by the minute [in online quotes]. ... It allows for things like offering incentives for buying insurance. None of that is allowed here."

Then, there is a cultural component. Bennett observes that Europeans are more apt to take precautions against potential misfortune, whereas Americans are "perhaps overly optimistic about how life will go in the future." She calls it an endearing trait that, however, does not promote a buy-insurance mentality.

Can its appeal be boosted?

To increase pet insurance's draw in North America, Bennett and others suggest insurers diversify their offerings, providing options for limited coverage that costs less. NAPHIA's premium data shows policies that encompass preventive care cost significantly more than those covering accidents and illness only. For dogs, the more expansive coverage is upwards of $1,200 per year on average, compared with under $700 for accident and illness policies. In Canada, the price difference is more than twofold — exceeding CA$2,100 vs. CA$941.

Bennett suggested that prices could be further contained by eliminating coverage for more common, lower cost, relatively minor issues like allergies and ear infections, while providing full coverage for serious, more costly conditions like cancer, broken bones and gastric torsion.

Wilkerson, the veterinarian who maintains an online guide to pet insurance, is wary of seeing coverage diminished. "Maybe there's no product here," she ventured. "If there's no way to make this a win-win — if you can't give pet owners what they need to cover costs and you can't make a profit — what does that tell you?"

Her agnostic view toward pet insurance is common among U.S. veterinarians, many of whom do not want veterinary medicine to become controlled by private insurers as human medicine is.

Kruse, the veterinarian who spent two decades in the pet insurance industry, noted, too, that most practitioners are plenty busy and not looking for the additional traffic that might result if more pets were insured.

"Can the profession handle even more business?" he asked rhetorically. "There are a lot of competing factors [against pet insurance] when you look at the broad spectrum of things. It's a dilemma."