Loan expert says veterinarians with high debt may benefit by adjusting their strategy

Varried borrower paths

As the pandemic pause on student debt interest in the United States comes to an end, borrowers have two novel ways to potentially wrestle down their payments. One is available for a few more months. The other is available for the foreseeable future.

On Sept. 1, interest started accruing again on federal student loans, ending a 42-month special pandemic forbearance during which interest stopped and payments weren't due. Payments resume in October.

The first novel benefit available to educational borrowers is one that may require taking action in a matter of months. It is a one-time account adjustment by the U.S. Department of Education to correct what the agency calls "historical failures in administration of the federal student loan program," which shortchanged borrowers on time they've spent paying on their loans.

The time, or payment count, is critical for borrowers seeking to qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or who are otherwise using income-driven repayment plans. In both instances, borrowers may achieve forgiveness of their debt balances after logging a specified amount of "qualifying time" in repayment — from 10 to 25 years, depending on the plan.

By comparison, the standard payment plan requires repaying the full amount owed, plus interest, in 10 years, regardless of ability to pay.

The second novel benefit is a new income-driven loan repayment plan dubbed Saving on a Valuable Education, or SAVE.

SAVE replaces a plan called Revised Pay As You Earn, or REPAYE, which is one of several income-driven repayment options. (The first income-driven plan was introduced nearly 30 years ago, and there have been additions and revisions ever since.) For a variety of reasons, SAVE is widely considered a great choice, although it's not the most beneficial for everyone; it depends on individual circumstances.

The new programs come during what has been a period of high activity and one major stymied attempt at student debt relief by the Biden administration, leaving borrowers juggling hope, fear and confusion.

To explore the options available and how they may affect borrowers, the VIN News Service spoke with several veterinarians with school debt as well as a student loan management expert who is also a veterinarian.

A happy, life-changing surprise

Announced in April 2022, the payment count adjustment has already brought absolution to some borrowers. Dr. Claire McNesby is one of them.

A practice co-owner and mother of three, McNesby began paying on her loans in 1999, following an internship she completed after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Her balance at the outset was $277,000 — $7,000 from undergraduate days, the rest from veterinary school.

Like many advanced-degree holders, she had a mix of loans — some private, some government. McNesby also had government-backed loans that were held by private lenders, called Federal Family Education Loans, or FFEL, a program that was discontinued in 2010.

She paid off the private loans and, at times, changed repayment strategies on the government loans as part of managing her finances to accommodate the ebbs and flows of life. During periods while she was on maternity leave or between jobs, the loans went into forbearance — meaning payments weren't required but interest mounted.

As of early this year, her balance was just under $104,000, all in privately held FFELs. She expected she had 10 more years to go.

McNesby watched a webinar about student debt, one in a collection of such programs on the topic offered by the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, and its nonprofit affiliate, the VIN Foundation. Afterward, she sought advice from Dr. Tony Bartels, a student loan consultant at VIN and the VIN Foundation. From Bartels, McNesby learned that by applying for a federal loan consolidation, she would become eligible for the recount, potentially receiving credit for the months when she was in forbearance as well as time she spent in various repayment plans.

The recount happens automatically for borrowers of federally held student loans but not for borrowers with the quasi-federal loans. To make the payments on those privately held loans eligible for the recount, those borrowers must apply to consolidate them into federally held loans by April 30.

McNesby promptly consolidated, then prepared to be patient. "I was thinking I wouldn't hear [anything] until next year," she said.

But in July, an email arrived from the Department of Education saying she was eligible for forgiveness. The agency offered congratulations, along with a chance to opt out, noting that forgiven balances are taxed as income by some states. (Forgiven balances usually are also subject to federal income tax, but a law providing coronavirus pandemic relief exempts discharges made between 2021 and 2025.)

McNesby isn't sure whether her state, Maryland, taxes forgiven student debt — she thinks it doesn't — but in any case, she did not opt out. She also, at that point, was somewhat dubious that her loan really would be forgiven. "I was, like, 'Uhhhh, maybe?' " she said.

Debt forgiveness

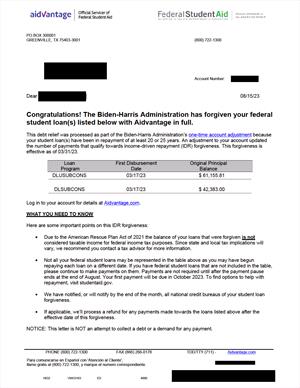

Dr. Claire McNesby was overcome with emotion when she opened the email bearing the news that she had completed her repayment obligation on student loans.

Click here for a larger view.

Then, at 8 p.m. on Aug. 18, while outside with the dogs, she checked email on her mobile phone. She screamed.

"I ran inside and told my husband," she recalled. "He said, 'You're screwing with me.' "

"Why would I joke about that?" she wondered, even though she could barely believe it herself. She showed him the email that reads, "Congratulations! The Biden-Harris Administration has forgiven your federal student loan(s) listed below ... in full."

McNesby doesn't know exactly how much she's paid on her loans over the 24 years since graduation but figures she's covered the principal and then some. A projection she received shortly after graduation showed her payments would total nearly $400,000.

Before the life-changing Department of Education email arrived, McNesby worried about how she and her husband would cover their children's college expenses. "It's been a bit of a scrape," she said.

The eldest is done with undergraduate studies, but the middle daughter is in the midst of hers, and the youngest will start in a year.

"I didn't know how I'd swing that, basically paying mine and two kids' [school expenses]," said McNesby, whose monthly loan payments had been $1,100. "I was sweating it. I thought we'd have to get a parent loan."

Now, they won't.

When SAVE is the better plan and when it's not

For borrowers who haven't amassed years of payments like McNesby, the government recount may reduce their remaining repayment time but not bring them to a zero balance. Or it may not change anything at all.

That's the case for Dr. KC VanFleet, who began repaying his loans following graduation from veterinary school at Michigan State University six years ago. His loans were never in forbearance, deferment or any of the other situations in which borrowers weren't credited with time in repayment. After the recount, he'll still be at six years down.

But how many more years would he have to go? That's the question VanFleet needed to explore. Under the income-driven repayment plan that he's in, called Pay As You Earn, or PAYE, he's obligated to make payments for no more than 20 years. After that, any remaining balance is forgiven.

The new income-driven repayment plan, SAVE, requires 25 years of payments to reach forgiveness by borrowers of graduate-school loans. On the basis of time alone, PAYE would seem to be the better plan. But SAVE has some distinct advantages.

A big difference is that the government will not charge any monthly interest that isn't covered by the borrower's payment. In other words, if a borrower's calculated SAVE payment doesn't fully cover the monthly interest (never mind principal), the Department of Education covers that remaining interest. As a result, anyone using SAVE will not see their balances grow due to unpaid interest, which can happen with other income-driven repayment plans.

"We're seeing that highly motivating for people" to make the switch to SAVE, Bartels told VIN News.

The fact that interest doesn't accrue, he added, also nicely caps the amount that would be forgiven at the end of the repayment period for those borrowers who complete repayment with a balance. That makes any related tax bill generally lower and more predictable. "You now know, 'I can never have more than X dollars forgiven,' " Bartels said, "and that makes planning for the tax payment a little bit easier and a little bit more certain."

In addition, the way monthly payments are calculated under SAVE are more generous to the borrower than under other repayment plans.

These reasons make choosing SAVE a no-brainer for those just finishing school, according to Bartels: "It makes the payment plan selection process of future new graduates super-easy. Everybody should choose SAVE from the get-go."

For those already some years into repayment, though, the choice isn't necessarily as clear-cut.

VanFleet, who pays close attention to student-debt developments, said he'd heard rave reviews about SAVE from multiple sources. He wondered whether he should switch.

Besides, his PAYE repayment plan is being phased out, so VanFleet wasn't sure that he even had the option to stick with it. He learned later that anyone already in the program may remain, but if they leave, they cannot return.

What to do? When figuring out something as complex as how to pay off $211,613 in debt, plus unpaid interest of $22,336, over the next one to two decades, calculations on the back of a napkin won't suffice. VanFleet turned to a free student loan repayment simulator provided by the VIN Foundation.

The answer: VanFleet would do better with PAYE than SAVE, saving some $16,000 over the long run, even after taxes. Why? Mostly because he'd reach forgiveness earlier — in 14 years rather than 19.

Should VanFleet's financial situation change markedly — and it may well, because he and his wife are planning to open their own practice next year, and they have a second child on the way — he said he'll run a fresh simulation to see whether the guidance changes.

For now, his direction is clear. For other borrowers in PAYE, the decision to stay or switch is harder, Bartels said. Those are people who may appear to benefit from the lower monthly payments afforded by SAVE but who, depending on forgiveness count and changes to their future income and family specifics, could do better under PAYE by reaching forgiveness earlier.

The dilemma for such borrowers — generally, people who have been in repayment for around 10 years — is that they must make a decision that depends on their future income, which they have no way of knowing, Bartels said, calling the decision "nerve-wracking."

In the absence of crystal balls, Bartels said the choice comes down to: "Do you want to be done five years earlier or do you want to not see your balance grow with interest, have a lower monthly payment and have more certainty on the amount that's forgiven?"

A Public Service Loan Forgiveness twist

Dr. Kelly Hunter faces a nerve-wracking decision of a different kind. An employee at the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 2015, she is working toward forgiveness in 2025 of the balance of her $215,000 veterinary school loan under PSLF.

(Hunter is a pseudonym for the borrower, who asked not to be identified in order to protect her financial privacy.)

Following veterinary school, Hunter borrowed $30,000 to pursue a master's in public health. As a result, she has two separate loans, the bigger of the two being closer to reaching forgiveness.

Bartels advised Hunter that if she consolidates, her master's-degree loan would be put on the same forgiveness clock as her veterinary school loan.

If she doesn't consolidate, Bartels said, Hunter will likely end up paying off the $30,000 master's-degree loan in full rather than having a forgiven balance, since the sum is relatively small. In other words, consolidating would save her a good chunk of that $30,000 and maybe more.

So what's the quandary? According to the Department of Education, "borrowers who consolidate will have their PSLF counts temporarily reset to zero, and those counts will begin adjusting in Fall 2023."

Even though it's temporary, the "reset to zero" part seriously rattles Hunter.

"To see your payment count go down to zero, that may give me a coronary," she said.

Arduous experience managing her loans and getting on track with PSLF makes her wary. Right now, she's credited with 96 of the needed 120 months in repayment to reach forgiveness on her veterinary school loans.

"That 96 has been hard earned with blood, sweat and tears, including so so so many hours on the phone with FedLoan Servicing and a FOIA request to boot," she told Bartels on a VIN message board, speaking of her former loan servicer and having to resort to a Freedom of Information Act request to obtain her payment record from the federal government. "It has taken me years to get the count correct on my vet school loans. I am going to be honest — I am scared to mess with that."

Hunter told VIN News that the records she received filled 974 pages that she had to dig through for documentation of her PSLF qualifying payments to show the loan servicer.

Another thing that gives her pause is the prospect of legal challenges attempting to stop the federal government from forgiving loans through the count adjustment. One such challenge was dismissed last month, but she worries more will follow.

"That's why it makes me really nervous," she said. "If this gets shot down in a lawsuit, I don't want to go back to zero when I'm eight years in."

For now, her plan is to sit tight and watch events unfold. "If everything stays the same with the one-time count adjustment, I will consolidate," she said, "but it'll be later in the year."

This article was changed on Jan. 2, 2024, to reflect a new U.S. Department of Education deadline for applying to consolidate loans to make them eligible for the one-time forgiveness count review and possible adjustment. The updated deadline is April 30.