UCD School of Veterinary Medicine

Photo courtesy of University College Dublin

University College Dublin has been offering Ireland's only veterinary program since 1946.

Ireland has taken initial steps toward building its second veterinary school, a move that could see it overtake plans for a school in Northern Ireland that have been mired in delays.

Ireland's government has invited expressions of interest, due Nov. 18, from educational institutions that want to expand or create new veterinary medicine courses for academic year 2024-25 or 2025-26. The invitation is open for courses in dentistry, pharmacy, medicine and nursing, as well.

Ireland, also known as the Republic of Ireland, has one veterinary program, established in 1946 at University College Dublin.

"Ensuring a supply of qualified vets to meet the demands of the sector is a priority for my department," Ireland's higher education minister, Simon Harris, told the country's parliament last month while announcing that the expressions-of-interest process was in the works.

Still, he said, "significant practical elements" would need to be addressed to add new veterinary education capacity, including the construction of "appropriate laboratory facilities" that meet the standards of the industry regulator, Veterinary Council of Ireland (VCI).

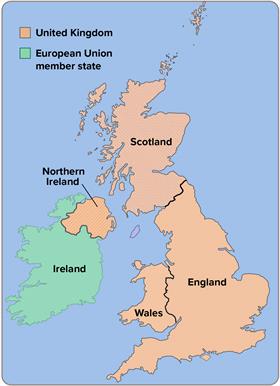

Northern Ireland, meanwhile, which is part of the United Kingdom, announced in March 2021 that it was studying the merits of building its first veterinary school. Almost 20 months later, the results of that study, completed last year, have yet to be made public, prompting one lawmaker to accuse the government of "kicking the can down the road."

Scoping work for a veterinary school is "ongoing," Northern Ireland's Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs said in a statement to the VIN News Service. The department said it still is in discussions with two universities that might host a veterinary school in Northern Ireland: Queens University and Ulster University. It declined to reveal the results of the completed scoping study or say why the results had not yet been made public.

The fluctuating plans for veterinary schools in Ireland and Northern Ireland come as the U.K.'s exit from the European Union in early 2020, known as Brexit, continues to cause political turmoil across the Irish Sea.

Disagreement over how trade should be conducted between the U.K., Ireland, Northern Ireland and the EU has caused a political stalemate in Northern Ireland, disrupting the ability of lawmakers there to approve legislation — including investments in educational infrastructure such as veterinary schools.

Political tensions in Northern Ireland also are underpinned by speculation that the entire island of Ireland could soon become a single, unified country. The speculation is driven, in part, by the fact that most of Northern Ireland's citizens voted in the Brexit referendum to stay in the EU, of which Ireland is a member state.

Moreover, Catholics in Northern Ireland, who traditionally are aligned with Ireland, now outnumber Protestants, who traditionally are aligned with the U.K. To be sure, some fear a push toward unification could reignite violence between militant Unionist and Republican groups that was cooled by a peace pact signed in 1998 known as the Good Friday Agreement.

However things pan out, the current political deadlock in Northern Ireland means that its southern neighbor currently is enjoying more political stability.

The Irish government's Higher Education Authority, once it has received expressions of interest to expand Ireland's veterinary school capacity, is expected to whittle favored candidates before launching a formal tender process.

Does Ireland need more veterinary graduates?

Worldwide, the construction of new veterinary schools and planning for more continues apace after the pandemic sparked rising demand for pet care. A more recent slowdown in the global economy, however, could ease that demand — potentially fanning concerns that too many graduates are coming down the pike.

University College Dublin welcomed 94 students to its undergraduate veterinary program for the current academic year and 53 students into its graduate program. The veterinary school's communications manager, Helen Graham, couldn't provide a percentage breakdown of domestic and international students, saying only that "the majority" of students in the undergraduate program were locals. The school received accreditation from the American Veterinary Medical Association in 2020 and also is accredited by official bodies in the U.K., Europe and Australasia.

Supporters of a new school in Ireland contend that it is needed to plug a chronic shortage of talent, especially for large and mixed animal practices in rural communities. The shortage, they say, exists even though Ireland, as a member of the EU, has more porous borders for international students than the U.K. Moreover, freedom of movement still is permitted for people between Ireland, Northern Ireland and the rest of the U.K.

chart_map_UK_Ireland

Art by Tamara Rees. Source: Adobestock/lesniewski

All that porosity has created a problem in itself, according to Dr. James Quinn, a large animal veterinarian who is lobbying for a new veterinary school in Ireland.

He points out that of the 259 veterinarians who registered last year with the VCI, fewer than one-third studied in Ireland. He said many study in Eastern European countries such as Poland, Hungary and Slovakia because there are too few training places at home, and living costs in those countries are lower than in Western Europe.

"There is a recognized pinch point in the educational system here in that there is only approximately between 70 and 80 training places available annually to domestic students in the one provider, which is University College Dublin," Quinn said, making an estimate on a figure that was unavailable from the university.

The result, he said, is that a small proportion of graduates have been suitably trained to service Ireland's large and mixed animal practices. "A lot of the practice types here require people who are multiskilled across the species," Quinn said. "And there's a particular niche issue at the moment that filling those roles is becoming increasingly more difficult, even though the overall number of vets produced has probably increased."

Consequently, Quinn said, for any new school, factors such as its geographic location within Ireland, course design and student selection criteria might be tailored to attract aspiring large animal veterinarians prepared to work in rural communities. He acknowledges University College Dublin could apply to expand its capacity but would prefer to see a new school established closer to Ireland's farming regions — not a capital city such as Dublin — and expects five other educational institutions, including universities in Limerick and Cork, will participate in the expressions-of-interest process.

VCI figures indicate that a large proportion of Ireland's veterinarians train overseas. In 2021, for instance, of the 259 veterinarians who joined its register, 28% had graduated in Ireland. Of the 138 new graduates included in that number, 41% had studied in Ireland.

"The VCI would welcome increased places for veterinary medicine education in Ireland, acknowledging the anecdotal references to increasing numbers of Irish students attending veterinary medicine courses abroad," VCI chief executive Niamh Muldoon said by email. The numbers of veterinary practitioners in Ireland "have never been higher," she added, with 3,387 veterinarians and 1,229 veterinary nurses now registered. "However, anecdotally, we acknowledge the challenges in recruitment and retention of vets and vet nurses."

Among those seeing a shortage of veterinarians is XLVets Ireland, a cooperative for independent practices that offers pooled purchasing, training, business development and recruitment services to help them compete with consolidators.

XLVets Ireland has 28 member businesses that own 50 practices in Ireland employing a combined 190 veterinarians. When surveyed earlier this year, the owners of those practices said they were running at about 88% of their desired veterinarian staffing levels, XLVets chief executive Mike Curran said.

"Vacant positions are currently being filled by vets qualified across the U.K. and Europe, but as a producer of premium agricultural products, Ireland can also become a leader in the education of vets," Curran said. "A larger domestic education system could provide a foundation for Irish people who want to become vets, or people around the world who want to come and train as a vet in Ireland."

Quinn, the large animal veterinarian pushing for a new veterinary school, last November set up the Veterinary Working Group, an informal association of like-minded practitioners interested in expanding veterinary education in Ireland. The group has met with higher education minister Harris, whom Quinn said was receptive to its concerns.

"The minister seemed genuinely motivated to do something about this issue when he was presented with the figures showing the large number of students who are leaving the country because of lack of training places here," he said. "Suddenly, there was a political awareness that an anomalous situation had come into existence that one school that served its purpose more than 50 years ago is probably not serving its entire purpose now."

In Northern Ireland, patience required

Across the border in Northern Ireland, Dr. Rosalind Woodside is among practitioners who would like to see plans for a veterinary school there get back on track. "I think we really need one," Woodside, the principal of a practice in Gleno, said. "It's been very, very difficult finding veterinarians for our practice for the last few years; almost impossible.”

Having taken on two new graduates this year, Woodside's mixed animal practice employs eight veterinarians. She'd like to have nine.

A problem with not having a local veterinary school, she said, is that aspiring practitioners must cross borders to train — and could well end up staying outside the country.

"Veterinary students from here all go mostly to [elsewhere in] the U.K. and some go to the south, to Dublin," Woodside said. "So whenever they graduate, they have friends over in that part of the world. They tend to take their first job, possibly, in the U.K., and then they get settled there, meet people, and stay.”

Woodside, too, hopes that when designing a curriculum and considering entry criteria, the leaders of any new school are conscious of the need to attract at least some applicants with experience on farms or an interest in large animals.

Claims of a shortage of veterinarians across the U.K., including in Northern Ireland, regularly have been voiced by professional bodies, including the British Veterinary Association. The president of its Northern Ireland branch, Dr. Fiona McFarland, said a "marked workforce shortage" has been exacerbated by Brexit, COVID-19 and a boom in pet ownership.

"In the longer term, a new vet school in Northern Ireland has the potential to help build resilience into the profession by attracting more people into veterinary medicine and, therefore, creating a steady stream of future vets," McFarland said by email.

"We also believe that a new vet school would act as a focus for attracting talent and creating a hub of innovation for the veterinary sector. However, at the BVA, we have been clear that for a new vet school to succeed, it needs adequate funding, staffing and resources."