Lisa Greenhill

Photo courtesy of Lisa Greenhill

Lisa Greenhill is an advocate for underrepresented minorities in the veterinary profession and studies ways to combat racism.

Lisa Greenhill knows who she is and from where she came. She's unapologetically herself. And she's been entrenched in matters of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) for decades.

Perhaps it's for those reasons — combined with her reputation as a commanding public speaker with deep institutional knowledge of student populations and enrollment trends — that in an almost entirely white profession, the upper echelons of organized veterinary medicine flock to her lectures. She speaks on student debt and demographics, veterinary school applicants and the status of disproportionately underrepresented groups in the profession.

Her life's work to convey the inequities experienced by racial and ethnic minorities, confront bias and debunk stereotypes has earned Greenhill recognition as a standout in veterinary medicine. And she's hard to miss. With curls tinted lavender or blue, Greenhill, 48, is Black — a racial demographic uncommon in the veterinary community. Just one out of 10 veterinarians is a person of color. Black veterinarians number even fewer.

And Greenhill — gasp! — is not a veterinarian. Yet she is breaking barriers in a profession that's as exclusive as it is homogenous. Few non-veterinarians draw as much esteem from members of the profession as Greenhill, who holds a master's in public administration and doctorate in education. Her wide rapport with the profession has been cultivated over 20-some years with the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges in Washington, D.C., where she's the senior director for institutional research and diversity.

Her role has gained greater prominence since the world rose up last year in response to the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, which have spurred renewed conversations across the country about racism and police brutality. For its part, organized veterinary medicine has voiced a commitment to diversity, inclusion and the equitable treatment of all people, no matter their race or ethnicity, gender identity or sexual orientation. Whereas few affinity groups recognizing marginalized people existed in the veterinary sphere a decade ago, more than a dozen exist today, including the National Association for Black Veterinarians, Black DVM Network, Association of Asian Veterinary Medical Professionals, the Pride Veterinary Medical Community, American Association of Veterinarians of Indian Origin, and Multicultural Veterinary Medical Association.

The backbone of their work often draws on research and data collated by Greenhill, whom AAVMC Chief Executive Officer Dr. Andrew Maccabe credits for making his organization the profession's "pre-eminent leader and adviser" on the topic. "Dr. Greenhill has an incredible wealth of experience and expertise in diversity, equity and inclusion," he said. "... She has a great passion for this work and, even more important, great compassion for those who are trying to understand these issues and navigate this space.

"On a more personal note, Lisa has been a true inspiration for me and a trusted guide along my own journey of discovery about DEI," continued Maccabe, who is white.

Greenhill was hired by the AAVMC in 2004 to develop and lead DiVersity Matters, an initiative that promotes the veterinary profession within communities of color, and she's worked for the organization on and off since. Her role has evolved to include collecting and disseminating data on the 12,000-plus veterinary students in the United States, as well as tracking the applicant pool. She's a frequent speaker at events. On the YouTube channel AAVMC Diversity & Inclusion on Air, she explores the recruitment and retention of underrepresented minorities and hosts discussions about what it means to be non-white in veterinary medicine.

"So much has changed over the years, and I feel like we've made really incredible strides, but as with everything, there's always much more work to be done," she said in a July episode with Maccabe.

Maccabe responded by characterizing the profession's lack of diversity an "existential threat" to its future. "… I really do believe that the single most important issue that we have to deal with in the profession is the topic of diversity," he said.

Under the DiVersity Matters initiative, AAVMC has maintained a consistent presence recruiting at undergraduate science, technology, engineering and math conferences that focus on people of color. Greenhill says she's encountered numerous students at those events who eventually go on to veterinary school, which is "super rewarding." Many veterinary colleges, she said, now join AAVMC in its recruiting efforts and see a return on that investment. AAVMC also recruits at its annual conference, hosting students from across the country who have an interest in veterinary education; at least a third of them are from underrepresented backgrounds.

Since DiVersity Matters was established in 2005, enrollment of underrepresented minority students in veterinary school has more than doubled. Last year, it was 21.1%, Maccabe said.

The work, Greenhill says, can't be limited to recruitment. Under her direction, AAVMC has focused on promoting inclusion within academic veterinary medicine. "I've conducted multiple studies on college climate, and the colleges have used that data to make policy and sometimes structural changes on campus," she said.

It's equally important to infuse veterinary curricula with content that helps students and professionals understand how issues of diversity, equity and inclusion are relevant to veterinary practice, she continued. For that reason, she advocates making stronger diversity standards a part of veterinary accreditation. "It's not the job of students from marginalized backgrounds to educate their student colleagues; that should be a function of the curriculum," Greenhill said. "Additionally, because the numbers of underrepresented students remain less than parity, we have a responsibility to increase the knowledge base of all students so they are prepared to work in the 'real' world, which is far more diverse."

Asked if she ever feels like an outsider in an overwhelmingly white profession of which she's not a card-carrying member, Greenhill paused before responding.

"I care deeply about this profession, but I don't want to be a veterinarian, and I don't want to be mistaken for one," she said. "But frankly, I've felt far more isolated as a Black woman working in an overwhelmingly white and overwhelmingly male space. Discomfort isn't quite the right word, but it's very clear that I'm not like them.

"But that's my life experience," she continued, "so I'm not going to trip over that space."

'Who's black? I have brown skin'

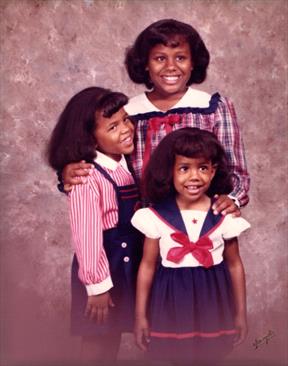

Lisa Greenhill

Photo courtesy of Lisa Greenhill

Greenhill and her younger sisters Karen (left) and Monica never considered careers in veterinary medicine. Karen works as an elementary school teacher and Monica is a manager at Google.

Greenhill grew up in 1970s segregated Richmond, Virginia, the daughter of Edward, a DuPont mechanic, and Angela, a homemaker who later worked in human resources. It was in preschool, Greenhill said, that she remembers learning that skin color mattered. A classmate's mother had openly chastised her daughter for playing with Greenhill, the "Black kid."

"It's one of my earliest memories," she recalled, "and I thought, 'Who's black? I have brown skin.' "

Her parents pulled her from the program and enrolled her in one that was more racially diverse, encouraging pride in her skin color while recognizing the unfairness of society. At home, they often spoke of racial inequities, acknowledging that they intentionally gave their daughters nondescript anglicized names.

Greenhill gets a kick out of it. "We call them our soap opera names," she laughed before turning serious. "They didn't want our ethnicity to affect treatment and opportunities; they wanted us not to be judged on paper."

As a middle schooler, Greenhill bused with her sisters across town to a district with a record of higher academic achievement. It was in a whiter part of town, where racial tensions ran high. "There were salt n' pepper wars," she recalls. "It was a time of racial reckoning, and people acted on the values they were learning in their homes."

But Greenhill was a good student, which she says cushioned her experience. "We were all bright and identified as gifted early on, and that smoothed a lot of our path," she said. "It's easier to succeed in those environments. I had wonderful teachers."

After high school, Greenhill accepted an academic scholarship to George Mason University in Virginia. She abandoned her original plan to become a lawyer after taking internships on Capitol Hill, first with Rep. Tom Bliley, chair of the Ways and Means Committee in the early 1990s.

"I didn't agree with his politics at all, but I learned a lot," Greenhill recalled. "I loved the Hill. I loved the policy work and politics, so I don't regret the experience [working with Bliley] ... it changed the trajectory of my life and my career."

During her senior year, Greenhill went to work for Rep. Cynthia McKinney, a Black politician and activist from Georgia, and thrived. "I worked on tobacco policy and health education," she recounted. "Richmond is a port city for tobacco and half of my family worked for Phillip Morris. I was still pretty young, but I understood the economics around tobacco and I really understood what it was like to economically rely on it."

Soon after graduating in 1995, she was hired by then-AAVMC Executive Director Dr. Lester Crawford as a legislative administrative assistant. She left three years later to pursue her master's degree, then worked as a research associate for the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

She went back to AAVMC in 2000, at the behest of Dr. Curt Mann, who had taken over for Crawford, hired to lead the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But her stay was short-lived. The AAVMC had been a victim of embezzlement and was at the brink of collapse. When Greenhill's paycheck bounced in early 2001, she left.

"I had a house in escrow, it was closing, and I had bills to pay," she recalled. "It was a devastating period."

Greenhill landed at the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, where she worked as a legislative manager until Dr. Larry Heider, at the helm of the AAVMC in 2004, lured her back to lead the organization's diversity endeavors. She was the first person to be hired at any veterinary medical organization in a full-time, permanent position to promote diversity.

Lisa and Leanndra

Photo courtesy of Lisa Greenhill

Greenhill's daughter Leanndra, now 19, graduated from a small military boarding school in Virginia, where she was in the Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps for the Air Force. Before sending her, Greenhill made sure other students of minority backgrounds attended the program.

"I'm so proud of Dr. Heider, that he had that vision," Greenhill said. "We launched DiVersity Matters and it was a big moment for veterinary medicine. He had decided that this is where the future is, and we need to be a part of it. It was incredible foresight that really put us on the path we are now."

Along the way, she's cultivated a network of Black veterinarians and academicians who've acted as mentors, including her friend Patricia Lowrie, former director of the Women's Resource Center at Michigan State University; and veterinary college deans such as Drs. Philip Nelson (Western University), Willie Reed (Purdue University), Ruby Perry (Tuskegee University) and Michael Blackwell (formerly at the University of Tennessee, now with the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association).

"They mentored and coached me, supported me, cheered for me and defended me," Greenhill said. "I wouldn't be here but for them."

One mark of success

As the world evolves on the topic of diversity, more veterinarians of color are speaking out about their experiences with discrimination in the profession, and more white veterinarians are ready and willing to listen.

Greenhill is elated, taking it all in.

"I tell people a lot that one mark of success on this journey is that I don't have to be in the room all the time for folks to do right by this topic," she said. "The fact that I no longer have to be present for there to be a robust conversation about diversity and inclusion, that says a lot about how far we've come. People are really starting to give voice to the issue, because it's not just my job. It's everybody's job."