RVC Hawkshead Campus 320

The Royal Veterinary College photo

The Royal Veterinary College's Hawkshead Campus, north of London, is where students spend the last three years of their five-year undergraduate program, studying alongside veterinary nursing students and specialists-in-training. Nearly half of RVC's incoming students last year came from outside the U.K. and EU.

A controversial admissions cap has left some of Britain's biggest veterinary schools vulnerable to potential student shortfalls that some claim could worsen a workforce gap estimated to be leaving more than 10% of job vacancies unfilled.

The COVID-19 crisis already was threatening to put downward pressure on enrollment by keeping international students away.

Now, as part of its response to the pandemic, the United Kingdom's conservative government has placed a temporary cap on domestic student admissions for universities in England. Applying to new undergraduate students from the U.K. and European Union, it limits growth during the 2020-21 academic year to no more than 5% above the school's admission expectations before the pandemic hit. (Veterinary education in the U.K. typically is a five-year undergraduate program.)

An example of how the cap works: A university that anticipated 1,000 new local students this fall would be able to enroll no more than 1,050 to offset any decline in international enrollments. Universities exceeding the cap will have their government funding cut.

Separately, the U.K. government also has announced that universities in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will have the number of students they can take from England capped at 6.5% above their previous year's intake.

The caps were introduced to stop top-tier universities, facing a potential loss of foreign students due to the COVID-19 crisis, from gobbling up locals to plug the gap. Without the caps, it was feared that less-prestigious universities would have scant local students left to draw from, putting them out of business.

The British Veterinary Association, Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, and Veterinary Schools Council have written to U.K. universities minister Michelle Donelan requesting that all veterinary programs get a cap exemption, citing a shortage of skilled labor.

In their joint letter, they also expressed concern that universities could be tempted to cut back on admissions to their veterinary schools in order to beef up numbers in more profitable courses that don't require costly investments in clinical teaching facilities. The Veterinary Schools Council (VCS) does not yet know how its member universities will proceed on that front. "We haven’t received any reassurance yet, though we are assured that their response is forthcoming," VSC spokesperson Lucy Chislett said.

The U.K. government has said that an extra 5,000 admissions would be allowed for subjects related to human health care and another 5,000 for subjects of "strategic importance." On June 1, the government confirmed that veterinary medicine was among those subjects, which include architecture, biological sciences, chemistry, engineering and social work, among others. But it warned: "These places are not guaranteed, and no provider or institution should rely upon receiving additional places in their planning process."

The extent to which British universities will be hurt by COVID-19 travel restrictions also is uncertain. Foreign travel into the country is allowed currently, though governments around the world have either banned or discouraged international travel to prevent the highly-contagious disease from spreading, and airlines have dramatically cut international routes.

Most international students attend three schools

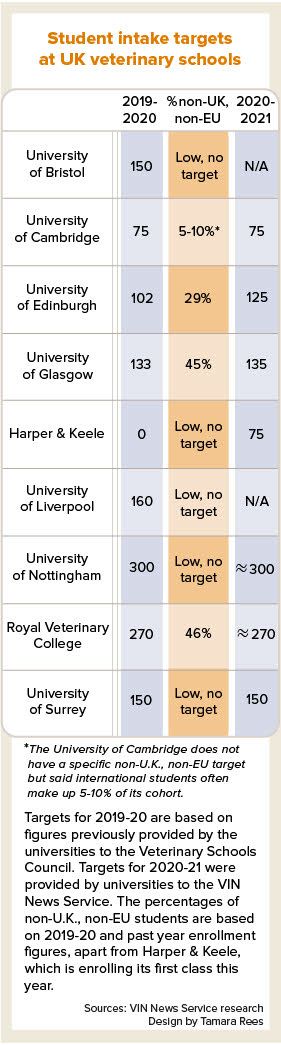

Historical admissions data indicates that three of Britain's nine veterinary schools accept the majority of international students: the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of Edinburgh and University of Glasgow. The RVC told VIN News that its admissions target for the 2020-21 academic year is "similar to last year's target." Last year, the RVC, which is part of the University of London, aimed to fill 270 places, including 125 students from outside the U.K. and EU, or 46% of the total.

Historical admissions data indicates that three of Britain's nine veterinary schools accept the majority of international students: the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of Edinburgh and University of Glasgow. The RVC told VIN News that its admissions target for the 2020-21 academic year is "similar to last year's target." Last year, the RVC, which is part of the University of London, aimed to fill 270 places, including 125 students from outside the U.K. and EU, or 46% of the total.

"Our indications to date are that we remain a popular destination," an RVC spokesperson said. "However, we won’t know the impact of the pandemic until students enroll." The RVC indicated that it does not intend to either raise or cut its intake target. "We are not planning on lowering our student numbers, nor expecting to have to do so," the spokesperson said.

Many students already partway through the RVC's veterinary program have packed their bags and left. "Our campuses have been closed to students since March. The majority of our students — home and international — returned home ..." the spokesperson said. When or whether repatriated students would return to the U.K. is unclear.

Although the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow are exposed only to the cap on students from England, the amount of government funding available per domestic student in Scotland is limited by the Scottish Funding Council. That means if schools there take on more Scottish, Welsh, Northern Irish or EU students than planned, they won't get much extra money from the government, which creates a cap by default.

Last year, of the 133 students the University of Glasgow aimed to enroll, 60 slots were for non-U.K., non-EU students, or 45% of the total, according to the VSC. A spokesperson for the university said its agreed student intake for the upcoming academic year was 135. However, she said it was impossible to make accurate predictions for this year's intake, due, in part, to uncertainty over foreign admissions. "We are not sure how travel restrictions and concerns amongst offer-holders will influence our international recruitment," she said.

A spokesperson for the University of Edinburgh declined to comment on the potential impact of the pandemic on its admissions target. He referred VIN News to the university's website, which states that the school is eyeing 125 places for its undergraduate veterinary medicine course this year, including 35 with a "graduate or international fee rate."

The RVC, University of Edinburgh and University of Glasgow all have accreditation from the American Veterinary Medical Association. A fourth British school, the University of Bristol, gained AVMA accreditation in October, giving it scope to woo U.S. students. A spokesperson for the University of Bristol declined to comment for this article.

Britain's five remaining veterinary schools typically take few to zero students from outside the U.K. and EU. University of Cambridge spokesperson Paul Seagrove said it is targeting 75 enrollments for its veterinary course this year, which is the same as last year. Foreign students, he said, "often make up 5-10% of our vet cohort, and we do not, as yet, have any indication that our 2020 intake will be much different."

The University of Nottingham, which last year doubled its annual veterinary student intake to 300, said it has already made its offers and will take "approximately the same numbers of students" as last year. "The school takes very few international students and has no specific target for these," spokesperson Emma Thorne said.

Thorne added that the University of Nottingham's student intake may be slightly higher this year, should more applicants than expected achieve high-level entry grades, known as A-levels. Summer exams for British high-school students have been canceled this year due to the pandemic, prompting the government to urge schools to take into account other evidence of achievement when assigning admission grades, such as previous exam results. Universities are preparing for multiple potential outcomes, including more students than usual meeting minimum grade requirements.

Newest school pressing ahead with opening plans

Britain's ninth and newest veterinary school, Harper & Keele, also may accept a few more students than the 75 originally planned, for what will be its first-ever cohort. Harper & Keele hasn't yet achieved accreditation from any professional bodies, including the RCVS, because it is just getting started.

"Regarding numbers, there is a feeling across the sector that, due to the approach taken towards A-level grading, there is likely to be a higher-than-usual proportion of students meeting their offer grades, so vet schools are anticipating having to potentially increase intakes to honor offers where feasible," the school's head, Matt Jones, told VIN News.

Harper & Keele already was planning to increase its cohort from 75 in its first year to 110 in its second. "We have undertaken all our planning on the basis of our maximum 110 cohort size, so are very relaxed about taking in a higher number of students," Jones said.

The University of Surrey, meanwhile, is targeting 150 students this year, as it did last year, a spokesperson said. Representatives for the University of Liverpool did not reply to requests for comment.

How everything turns out will be watched closely by the BVA and RCVS, which long have been warning of a widening skills crisis in the profession, owing, in part, to Britain's pending exit from the EU, in a process known as Brexit. The U.K. formally left the EU on Jan. 31 but is continuing to follow EU rules and maintain the trading relationship until a transition period ends Dec. 31.

Both organizations claim the profession already has a skills shortage of about 11-13%, which refers to the gap between job vacancies and the number of veterinarians who can fill them.

A spokesman for the RCVS, Luke Bishop, said the 11-13% estimate "is based on the vacancy rate, as provided to us by some of the U.K.'s biggest veterinary employers." He added: "Whilst it is an estimate, it is methodologically sound and we will soon be updating the data based on the current vacancy rates."

More than 60% of veterinarians registered in Britain in recent years graduated overseas, with the vast majority of those hailing from the EU, the three veterinary organizations stated in their joint letter. "We expect much greater difficulties in recruiting from EU member states once the Brexit transition period ends in early 2021," they said.

The potential for skills shortages has been recognized by Prime Minister Boris Johnson's government, which, despite its overall anti-immigration stance, recently put veterinarians back on the country's Shortage Occupations List, making it easier for local practices to hire foreigners.

This story has been changed to reflect that Jasmin De Vivo, a public relations contractor for the Royal Veterinary College, was passing on comments from a spokesperson at the college.