Dog Flu Spreading Fast Across U.S., Vets Issue Guidelines ... Dangerous strain of 'dog flu' coming for Idaho's canines ... Suburban vets on ‘red alert’ for dog flu

Dog Flu Spreading Fast Across U.S., Vets Issue Guidelines ... Dangerous strain of 'dog flu' coming for Idaho's canines ... Suburban vets on ‘red alert’ for dog flu

Considering ongoing headlines such as these, it would be easy for veterinarians and dog owners alike to view the spread of canine influenza virus, or dog flu, in the United States as a singular catastrophe.

While the recent emergence of a new strain understandably has captured public attention, the situation isn't novel or disastrous. Dr. Cynda Crawford, a University of Florida clinical assistant professor who in 2004 helped identify the first influenza virus known to affect dogs, suggests that experiences with influenza in other species provide a guide to managing the pathogen in canines.

“We should be looking at what has been well-established in people, pigs and horses,” said Crawford, who directs the Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program at UF.

Infection by influenza viruses in humans, horses, pigs and birds has been well understood for decades. The virus’ ability to spread and mutate with ease in these species is well documented, and the medical community has well-established vaccination and quarantine strategies to control outbreaks, especially among horses and humans.

It was from a horse influenza virus that the first canine influenza virus, known as H3N8 CIV, evolved. The first recognized outbreak occurred in 2004 among racing greyhounds in Florida. Since then, the virus has been documented in 41 states and Washington, D.C. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, it’s now endemic in parts of Colorado, Florida, New York and Pennsylvania.

The new strain, H3N2 CIV, evolved from an avian flu. It first appeared in southern China and South Korea about 10 years ago. Dr. Ed Dubovi, director of the Cornell University Animal Health Diagnostic Center, told the VIN News Service last year that he suspects the virus entered the United States through an infected animal rescued from Asia. The domestic outbreak began in March 2015 in Chicago.

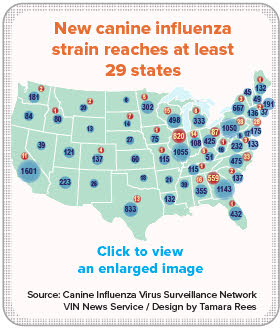

Between March 8 and Feb. 2, the Canine Influenza Virus Surveillance Network logged 1,693 positive tests for H3N2. Another 12,837 tests were negative. The results aren’t comprehensive. The information is derived from 12 diagnostic laboratories participating in surveillance.

Although currently drawing less notoriety than the new strain, H3N8 is still active in the United States, according to Dr. Jill Lopez, a spokeswoman for Merck Animal Health, which makes two of the four vaccines available for canine influenza. (Zoetis makes the other two.)

“There are still cases of H3N8 popping up,” Lopez told the VIN News Service by email, citing recent occurrences in Walla Walla, Washington, and Toledo, Ohio. “It is still out there and is something to be concerned about.”

At the same time, Lopez believes that the H3N2 virus is of greater concern. “When you compare the two, H3N2 is much more infectious. Within nine months, there were positive cases in half the country,” she said, adding that animal infected with H3N2 may be contagious for a longer period, as well.

However Dr. Melissa Kennedy, a virologist at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine, cautioned that at this point, any evidence of H3N2 being more virulent is only anecdotal.

What are signs of canine influenza?

- Coughing that persists up to 30 days; may be moist or dry like kennel cough

- Lethargy

- Low appetite

- Fever

- Sneezing

- Discharge from the eyes and/or nose

- Rapid onset of signs

- High fever (104 F to 106 F)

- Signs of pneumonia such as difficulty breathing, rapid breathing and blood from lungs

How new strains arise

Flu viruses are expert shape-shifters, able to take new forms abruptly. Known as antigenic shift, this transformation occurs when two different flu strains infect the same cell and combine, creating a new flu subtype, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kennedy, describes influenza as a chameleon, saying it takes mutation in only one host to exchange whole genes in an influenza strain. In other words, a mutation in one patient can produce a new influenza strain, resulting in an entirely new outbreak.

“I expect to see new [canine] strains emerge continually, because it’s going to continue to circulate. If those mutations give the virus an advantage, they’ll be sustained,” she said.

Influenza’s propensity to change raises questions about effective vaccination protocol in dogs.

Dr. Alice Wolf, an infectious diseases specialist and a consultant for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, points out that for humans, influenza vaccines are modified yearly.

“They look at influenza strains that are circulating in Southeast Asia and make a guess a year in advance as to which strains will be important. That’s why they recommend yearly vaccination for humans,” she said.

Vaccines for dogs are available against both strains known to infect dogs, but they are separate vaccines; none is known to protect against both strains at once. For that reason, a decision to vaccinate is something of an undertaking.

“If you really think it’s a big deal, you need to use both vaccines, and start with two doses for each,” Wolf said. “Then, if every year if you’re going to booster, that’s two additional vaccines this pet needs.”

She added: “What if we get an H3N5? Do you vaccinate against all three?”

Wolf’s inclination is to not vaccinate dogs without a compelling reason, such as a local outbreak, travel to a location with an outbreak, or routine high exposure to other dogs. She noted, “There are lots of kinds of equine flu and we don’t vaccinate against all of them.”

According to the American Association of Equine Practitioners, two subtypes of equine influenza virus are known to be circulating in the world. Multiple strains of each subtype exist. Vaccines are reformulated periodically to protect against the most commonly reported strains. Horses that are vaccinated against equine influenza virus typically receive booster doses every six to 12 months.

Crawford sees a different lesson in the horse experience from Wolf. “The AAEP states that all horses should be vaccinated against equine influenza unless they live in a closed and isolated facility,” she said.

“If we look at [the vaccination strategy for] horses,” she went on, “we could propose that because most of the dog population in the U.S. has no immunity to H3N2 or N8, and most dogs have a social lifestyle, perhaps we should evaluate if all dogs should be vaccinated to increase the population immunity.”

Crawford pointed to an equine influenza outbreak in Australia in 2007 to illustrate how influenza spread may be controlled through vaccination. “They vaccinated all horses in a [geographic] ring around the infected premises,” she said. “They created an immune barrier; that’s what eventually stopped the transmission.”

In an account of the outbreak, the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries describes using quarantine to slow the immediate spread of disease and vaccinating horses to create a buffer zone.

Crawford suggested a similar tactic could be employed to curtail the spread of canine influenza in the United States, by vaccinating all dogs in states or regions with known virus, as well as dogs participating in social events.

Kennedy, the University of Tennessee virologist, said vaccination is needed mostly in dogs attending shows or agility trials or being boarded. She said boarding is the most likely source of outbreaks because “there is shared air space, high population density and sustained contact [between dogs].”

As for dog parks, Kennedy considers them “a risk, but not a high risk” for spreading canine influenza.

For owners who opt to vaccinate their dog or dogs, protecting against both strains is the sensible course. Wolf, Crawford and Kennedy agreed that there is little point in vaccinating against only one strain. Maintaining protection in vaccinated dogs requires yearly boosters.

Other factors in the spread of flu

Kennedy emphasized the importance of minimizing sick patients’ contact with not only their own kind, but all species. “If you are human and have the flu, I recommend you also avoid close contact with pets,” she said. “They have shown that human flu can also affect cats and ferrets.”

Kennedy pointed to an incident at the Nashville Zoo in 2007 in which H1N1 human flu was isolated from a colony of giant anteaters. According to an account in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, “The caretakers overseeing the colony, with the exception of the attending veterinarian, were also ill with respiratory disease, including the primary caretaker. The onset of the caretakers’ illness coincided with the illness in the anteaters.”

After an extensive diagnostic process to trace the origin of the anteater influenza, the culprit was determined to have originated in humans. Kennedy said the event resulted in restrictions being placed on visitors with active respiratory disease.

Environment also plays a significant role in the spread or containment of influenza, Kennedy said. Cooler temperatures, for instance, favor preserving the virus outside the body. While most other respiratory viruses die shortly after leaving the host, influenza contains proteins in its outer layer, or envelope, that help keep it viable. However, Kennedy added, “Influenza is easy to kill with any detergent; that’s one good thing.”

As tracking of canine influenza develops, Wolf, the infectious-disease specialist, worries about overwrought publicity leading to undue public alarm.

“Assessing risk is very difficult at this point,” she said. “But I know that veterinarians are in a quandary. There are all these press releases and news media, so clients are calling them. Veterinarians feel caught in a squeeze — what happens if they don’t recommend vaccination?

“There is a lot of publicity without a lot of scientific basis for the concern,” she said, suggesting that veterinarians consult colleagues in their respective areas to monitor respiratory disease in the region and assess risk to local dogs. “I think it’s wrong to have a lot of hysteria about it.”