Veterinary compounding in the United States has been described as the Wild West, with a mishmash of seemingly ever-changing regulations that differ from state to state.

Veterinary compounding in the United States has been described as the Wild West, with a mishmash of seemingly ever-changing regulations that differ from state to state.

Or, as Gigi Davidson, a veterinary pharmacist at North Carolina State University, put it: “The regulatory landscape is a little bit of a hot mess right now.”

While that mess is unlikely to be sorted out anytime soon, the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) aims to bring some order to the situation by updating its compounding standards. The recently proposed changes make it clear that the standards apply to all areas of compounding practice, not just for humans.

The USP is a nonprofit scientific organization that develops and disseminates guidelines for medicines, setting professional standards for pharmacy and drug manufacturers. Although not a regulatory body, USP standards often are used by rule-making agencies — such as state boards of pharmacy, medicine, or veterinary medicine — in whole or in part, as a framework on which to base regulations.

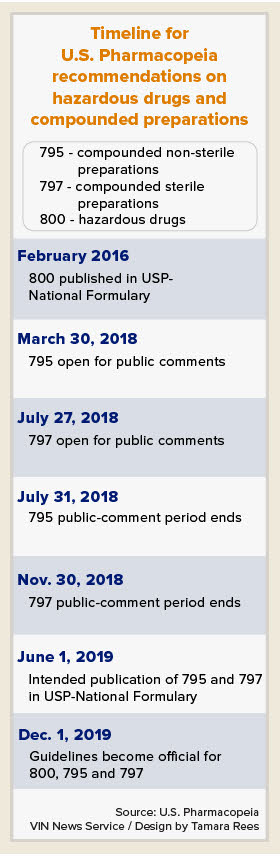

USP chapters 795 and 797 address non-sterile compounding and sterile compounding, respectively. In other activity affecting veterinary medicine, USP also recently finalized updates on chapter 800, relating to the handling of hazardous drugs.

Proposed changes to chapters 795 and 797 are in the public-comment phase. All three chapters are scheduled for rollout in December 2019.

Drug compounding is the modification of any medication from its FDA-approved form. In veterinary medicine, common modifications involving compounding include changes in strength, flavoring and route of administration.

While compounding of medications for human patients is coming under increasing oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the law pertaining to animal drugs – the Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act (AMDUCA) — is vague on compounding.

Why? Davidson, who chairs the USP Compounding Expert Committee, introduced the explanation this way during a recent seminar attended by pharmacists: “Some of your patients eat some of my patients.”

In other words, drugs given to animals used for food, such as cattle, can enter the human food-supply chain without careful controls. There are no such concerns about drugs given to animals kept only as pets, such as hamsters or cockatiels. And these types of very small animals require custom-made dosing for almost every drug. So, while a dairy-cow doctor may favor strict controls on veterinary compounding, parrot practitioners place greater priority on easy and almost instant access to compounded preparations for their patients.

Setting rules for species used for food and species that are never food doesn’t work, either. Davidson pointed out a historical lack of definition of what constitutes a food-producing species. Take pigs. They’re generally considered food animals, but some are kept as pets that will never become someone’s meal. Same with rabbits. So restrictions on drugs used for treating food animals could end up limiting treatment options for pets.

Reconciling those disparate interests in veterinary compounding is profoundly challenging; AMDUCA simply doesn’t go there.

The FDA has attempted to sort out the competing and sometimes conflicting interests, but appears so far to be stymied. Case in point: Draft guidance from the agency, dubbed GFI 230, ended up being pulled following more than two years in development.

Davidson said she believes the guidance was scrapped due at least in part to difficulty in bringing veterinarians and pharmacists together on the concept of reasonable restrictions.

“Food animal vets wanted it to be more restrictive. Exotics needed more leeway. ... It was all over the map,” she said. “...[T]hat’s one of my biggest concerns: Is it possible to make anything in veterinary medicine one-size-fits-all?”

But if veterinarians, pharmacists and regulators can’t sort it out on their own and Congress intervenes, the outcome is likely to be worse, she warned: “If it goes through Congress, it’ll go in looking like an aardvark and come out looking like a zebra.”

Who’s in charge?

At the state level, few boards of pharmacy or veterinary medical boards address veterinary compounding, according to Davidson. The lack of regulatory cohesion is an obstacle for veterinary compounders and veterinarians, she believes.

For example, what type of ingredients can be used in veterinary compounding? The regulations say nothing, or nothing clear, at either federal and state levels. Veterinary compounds must be prepared from existing federally approved drugs where available, rather than bulk chemicals, but AMDUCA does not mention bulk chemicals, and the regulations that implement AMDUCA are vague about their use, according to Davidson.

“All pharmacists who compound for animals are using bulk drug chemicals out of medical necessity,” she said in an interview with the VIN News Service. But whether that’s legally OK, she said, is unclear. “We have to get some guidance.”

She also points to unclear regulatory boundaries related to the supply chain for veterinary compounds. “Many veterinarians, if not all, get their office-use compounds from pharmacies in states that allow it,” she said, referring to the practice of compounding a drug in quantities enough for multiple hospital patients, or to dispense for outpatients.

Office-use compounding is another difficult area because most states’ laws specify that compounds be prepared at the time of need for an individual patient with a specific condition. Davidson said many veterinarians relying on office-use compounded preparations don’t realize that they are located in states that don’t allow office-use compounds.

Veterinarians, others, invited to weigh in

While it’s beyond the USP’s purview to resolve the thorny questions around bulk chemicals and in-office compounding, the organization aims to clarify the general issue of compounding by streamlining its standards.

The chapter 795 updates pertain to compounding non-sterile preparations, the area of compounding most relevant to most veterinary clinicians. The proposal includes a revised definition of non-sterile compounding. Whereas the previous version defined multiple categories of compounding, the updated definition is meant to be applicable across the board.

It reads:

For purposes of this chapter, nonsterile compounding is defined as combining, admixing, diluting, pooling, reconstituting other than as provided in the manufacturer package insert, or otherwise altering a drug or bulk drug substance to create a nonsterile medication. Reconstituting a conventionally manufactured nonsterile product in accordance with the directions contained in the approved labeling provided by the product’s manufacturer is not considered compounding as long as the product is prepared for an individual patient and not stored for future use.

The full revised chapter is posted online. USP is accepting public comments through July 31 on the proposed changes.

Comments may be submitted through an electronic form. Commenters are asked to list the line number they are referencing and give scientific rationale for their comments.

The proposed revision of USP chapter 797, relating to compounding sterile preparations, will be available for comments starting on July 27.

In the revision, certain practices no longer are considered compounding. An example is the addition of vitamins to an intravenous fluid solution to be given to a patient immediately. However, if a practitioner makes up a sterile drug in advance, not for a specific patient at the time, that action still is considered compounding.

One state’s example

California’s experience offers a look at the challenges in and processes for achieving legislative consistency with USP.

In 2017, the state implemented new legislation addressing veterinary compounding. In the months following rollout, the Board of Pharmacy and Veterinary Medical Board were confronted with widespread confusion among licensees.

Virginia Herold, executive officer of the California Board of Pharmacy, spoke of the growing pains involved in implementing new regulations. At the USP seminar in March, Herold reported that when the regulation took effect in 2017, half of the compounding inspections in pharmacies and hospitals that year resulted in correction notices.

Some of the compliance issues stemmed from discrepancies between the state rules and USP standards. For example, the rules for setting “beyond-use” dates for compounded preparations weren’t consistent — California’s being stricter than the USP’s.

So the state pharmacy board merged its regulatory standards with the USP standards (those currently in place, not the proposed updates).

Developing universally consistent standards is a work in progress. A number of compounding pharmacies in other states ship medications into California, so making the state regulations jibe with a national standard could reduce some confusion, Herold said: “The goal is to harmonize with our counterparts in other states.”

Another source of confusion in the compounding realm is regulatory jurisdiction. Pharmacy compounding usually is addressed by state boards of pharmacy, but those boards often don’t recognize or understand the use of compounded preparations in veterinary medicine. And boards that regulate veterinary medicine often don’t deal with pharmacy compounding.

That gap is being closed in California. A law enacted in 2017 directs the state Veterinary Medical Board to create regulations on the compounding practices of veterinarians.

Dr. Grant Miller, director of regulatory affairs for the California Veterinary Medical Association, suggested that it's an ongoing job ensuring regulations and standards for veterinary compounding align with one another, and make sense for the clinician.

Speaking of the USP draft chapters, Miller said the CVMA plans to submit comments "addressing areas in which the chapter conflicts with state regulations, and [we] are also providing feedback from a clinical-practice perspective in order to make the authors aware of areas in which veterinary practices differ from compounding pharmacies.”

Whether veterinary and pharmacy boards in other states will adopt the USP compounding standards remains to be seen. When asked by the VIN News Service about their approach to the USP 800 chapter on hazardous drugs, only a minority of states indicated that they were even familiar with the chapter.

Davidson strongly recommends that veterinarians contact their state veterinary boards to inquire whether they have taken or are anticipating taking a position on legal requirements for preparing, procuring and dispensing of veterinary compounds.

She suggests asking state veterinary and pharmacy boards for checklists of potential changes in state regulations related to each USP chapter.

“I encourage veterinarians to read all of USP’s proposed compounding standards to see how [the veterinarian] might be individually impacted,” Davidson said, adding, “I think 795 is going to impact them the most.”