!This story has an important update

In the year since a highly contagious viral disease that causes sudden death in rabbits was first identified in wild cottontails and jackrabbits in the United States and Mexico, the virus has spread quickly. Today, rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2) has been identified in 15 states mostly in the western U.S., 15 states in western and central Mexico, and three provinces in Canada.

In the year since a highly contagious viral disease that causes sudden death in rabbits was first identified in wild cottontails and jackrabbits in the United States and Mexico, the virus has spread quickly. Today, rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2) has been identified in 15 states mostly in the western U.S., 15 states in western and central Mexico, and three provinces in Canada.

The virus causes lesions throughout internal organs and tissues, particularly the liver, lungs and heart, resulting in bleeding, and is often fatal. It does not affect humans.

Many officials and veterinarians monitoring its spread believe it is only a matter of time before RHDV2, now classified as a foreign animal disease, is endemic in North America. They predict large numbers of jackrabbits and cottontails will die, disrupting ecosystems where they are an important food source.

In some cases, endangered native subspecies, such as riparian brush rabbits in California, could be wiped out by the virus. "Some rabbits are likely to go extinct," said Dr. Camille Fischer, a practitioner in California, a state that identified its first RHDV2 case in a black-tailed jackrabbit last May. "It's not a bunny problem. It's an everyone problem."

The spread among native or wild Leporidae (the family that includes rabbits and hares) has made unfeasible the strategy of battling the virus solely through rigorous biosecurity measures and isolating and containing positive cases. That approach worked with a different subtype of the virus, called RHDV1, which has been found to affect only the species of rabbit that has been domesticated, Orytolagus cuniculus, or European rabbit. RHDV1, endemic in Europe and elsewhere, hit several states in Mexico in the late 1980s. It popped up in isolated cases in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania and Utah between 2000 and 2018, and Manitoba, Canada, in 2011. That subtype has not resurfaced since; RHDV2 is proving to be a much more formidable foe.

As RHDV2 advances across North America, it echoes on a smaller stage the COVID-19 pandemic story of a highly infectious virus digging in and spreading fast. And as with COVID-19, there is general agreement that vaccines will be essential in combating — if not eliminating — the rabbit virus; and yet, vaccine accessibility is an uneven patchwork.

Accessing vaccines takes arduous effort

Rabbit owners in areas with outbreaks are stressed out, said Anne Martin, executive director of House Rabbit Society, a rabbit rescue and education organization based north of San Francisco. "People feel very vulnerable without having the rabbits vaccinated, especially when they see wild rabbits outside."

She describes biosecurity measures together with vaccination as the gold standard for protection. But accessing vaccines for this disease is not always possible. While Mexico launched a national vaccine in January, no RHD vaccines are produced or approved for commercial use in the U.S. or Canada. In Europe, where the rabbit virus is endemic, three RHDV2 vaccines are available — Eravac, Filavac and Nobivac Myxo-RHD Plus. Veterinarians in states with verified RHDV2 occurrences can import Eravac (from HIPRA in Spain) and Filavac (from Filavie in France) in limited quantities. British Columbia's chief veterinary officer imported Filavac to provide to veterinarians. Alberta has permitted at least one clinic to import vaccines on its own. Nobivac Myxo-RHD Plus, which debuted in Europe last May, is not available for export to the U.S. or Canada.

In the U.S., requests to import Filavac or Eravac are handled by states, which work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Center for Veterinary Biologics. In some jurisdictions, the state veterinarian imports and distributes vaccines to practitioners in the state; in others, veterinarians obtain the necessary permits to acquire the vaccines on their own.

In California, figures from the state veterinarian's office show that practitioners have individually imported about 30,000 vaccine doses so far. Demand remains high.

"I've been contacted twice, through the state vet's office, by veterinarians in the middle of the state looking for vaccines," Martin said. "It's just really spotty where people have access, and we've had the virus in our state for a year."

House Rabbit Society has acquired several thousand Eravac doses in several orders. Total cost, including shipping and the services of a customs broker, has run between $13 and $16 per single-dose vial, Martin said.

Importing the vaccine takes persistence and patience.

DVMs pickup RHD

Photo by Anne Martin

Northern California veterinarians Drs. Hilary Stern, left, and Marianne Brick picked up an order on May 1 of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus vaccines that came from Europe to San Francisco International Airport. Importing the vaccines is a long and winding process; the doctors were excited to receive the shipment.

Dr. Linda J. Siperstein was clinical director of a San Francisco Bay Area practice last May, when clients began calling for the vaccine. She spearheaded an order of 480 Filavac doses for a group of practices. During a month-long effort, she deployed her best "Franglish" in middle-of-the-night calls to Filavie to iron out details that "were not remotely intuitive if you are not familiar with shipping biologics from a foreign country," she said with a wry laugh.

The day the order was due to arrive at the San Francisco airport, Siperstein took time off from work to pick it up, only to learn that the temperature-sensitive shipment was coming by truck from Los Angeles, and the truck had broken down along the way. Her husband made the pickup in her stead the next day.

Waiting at work, she was tense with worry that the vaccines had gotten too warm and spoiled. "We have $9,000 worth of vaccine when you add in the shipping and the [customs] broker," she said. "One broken-down truck and it could be all be down the drain."

When her husband arrived with a huge box packed with layers of insulation, Siperstein's first move was to extract a USB device that was part of a temperature-tracking system, and plug it into her computer. "My eyes jumped to an X/Y axis graph. I could see the line go up, up, up, up. I said, 'No one uses this vaccine. It goes in the fridge now.' "

The next morning, she reported the readings to Filavie and was relieved to learn the vaccines were still good. But the hours of worry left an imprint. "I'm feeling nauseous right now remembering it," she said. "It all speaks to why we need a U.S. vaccine right now."

Veterinarians in states with no known positive cases, even those that border jurisdictions with positive cases, are not eligible for special import permits. They must wait for a confirmed case in their state to qualify. The rule seems nonsensical to Dr. Alicia McLaughlin, a Western Washington veterinarian who in 2019 was the first to import an RHD vaccine into the country.

"RHD isn't going to care one iota if there is a state boundary," McLaughlin said. "It's like saying, 'Well, my dog can't get heartworm because I live in a gated community.' "

She knows all about porous borders. RHDV2 was identified on Vancouver Island and the southwest coast of British Columbia in 2018. It cropped up the following year in Washington's San Juan Islands and northwest coast. The outbreak devastated populations of feral domestic rabbits on both sides of the international border.

What is rabbit hemorrhagic disease?

Highlighting the virus's complexity, the strain of RHDV2 that appeared in British Columbia and Washington is distinct from the one that roared out of the Southwest and Mexico last year, according to Dr. Amber Itle, a field veterinarian for Washington state. It has not impacted wild rabbits, and no cases have been detected in Washington since December 2019.

Dr. Adrian Walton, a veterinarian in Vancouver, British Columbia, said the strain of RHDV2 that hit the Pacific Northwest was particularly lethal and burned itself out as it killed off much of the susceptible population.

Consequently, rabbit owners in British Columbia have been less apt recently to vaccinate their pets. In the three years since Walton began vaccinating rabbits in late 2018, the number of vaccinations he's given each year has gone from 300 to 150 to — this year so far — about 60. Walton said news of RHDV2 in Idaho, Montana and, most recently, Alberta is likely to drive new spikes in requests for the vaccine — requests most veterinarians likely won't be able to fulfill quickly.

U.S. vaccine in the works

McLaughlin, the Washington veterinarian with the longest experience in obtaining RHDV vaccine from overseas, has become a go-to source for veterinarians learning to navigate federal importation regulations. So far, McLaughlin has imported two orders of Filavac and vaccinated around 1,000 rabbits.

She's contemplating a third order but the prospect of a coming domestically produced vaccine has her hesitating: She doesn't want to pay for imports that will take weeks to arrive, just as a possibly less expensive alternative becomes available.

"The officials I've talked to say, 'Oh yes, it's far along in the process. It's happening,' " she said.

The USDA declined to comment, but Medgene Labs, a biotechnology company in Brookings, South Dakota, confirmed to the VIN News Service last week that it is developing an RHDV2 vaccine. Founded in 2011, Medgene mostly focuses on developing vaccines for cows, pigs and deer, and providing disease surveillance for veterinarians and producers. The company said it is also developing a COVID-19 vaccine for mink.

"We began working on a vaccine for RHDV2 shortly after the first verified cases in wild rabbits in the U.S. in April 2020," CEO Mark Luecke said in an email interview. "We are in the process of generating the required safety and efficacy data for USDA approval. We have a reasonable expectation of both safety and efficacy based on our success with similar vaccines in multiple animal species across multiple disease targets, including multiple serotypes of EHD (epizootic hemorrhagic disease) in deer."

Medgene's vaccine design is different from that of Filavac and Eravac. The latter two vaccines use inactivated virus derived from the livers of rabbits infected in a lab. Medgene uses recombinant technology, similar to the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.

However, unlike those vaccines, which deliver genetic material into the body that prompts the body to build a viral protein that stimulates an immune response, Medgene’s vaccine delivers the immunogenic protein directly to the animal. "Therefore," Luecke said, "the probability of stimulating the right immune response is very high."

The Medgene approach doesn't require animals in its production, which makes it preferable to potential customers such as Martin at House Rabbit Society and Fischer, the California practitioner. They are eager to see a vaccine that is not only domestically produced but doesn't require infecting and euthanizing rabbits in order to protect other rabbits.

Mexico develops a national vaccine

Veterinarians waiting for a U.S. vaccine might look with envy to the south, where Mexico's federal government created and began deploying a vaccine within a year of the country's first confirmed RHDV2 case.

In April 2020, a rabbit meat producer in Chihuahua reported deaths in his herd of 30 rabbits, using an app called AVISE that enables anyone to report a suspected exotic animal disease. (AVISE is derived from avisar, Spanish for "to warn.") The Mexico-United States Commission for the Prevention of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and other Exotic Animal Diseases (known as CPA) contained the site, tested the animals and confirmed the country's index case.

Epidemiologists in Mexico studied that and subsequent cases "backwards and forwards," recounted Dr. Jorge Francisco Cañez de la Fuente, CPA regional coordinator based in Sonora. They traced the virus's entry to Mexico from Southern California and Arizona to Baja and Chihuahua.

They speculate the virus has spread mostly via wild rabbits and hares and possibly scavenging birds.

"Sometimes we have the cases where [people] … collected some herbs on the fields or even alfalfa … to feed their own rabbits," de la Fuente said. "Later on, we found jackrabbits dead on the alfalfa." He cited other cases in which people brought home wild baby rabbits or hares, acts that spread the virus to domestic rabbits in their households.

Initially, CPA calculated the virus was traveling about 14 kilometers (almost 9 miles) a day, de la Fuente said, but then it picked up speed, arriving in Central Mexico two months ahead of projections. As of April 15, Mexico had identified 269 cases in domestic rabbits in 15 states, and 27 cases in wild rabbits in 10 of those states. (Mexico has 32 states, including Mexico City.)

Most of the domestic cases have been among small-scale rabbit meat producers. Mexico has around 11,500 producers raising more than a million rabbits for meat. The majority are small "backyard" operations with limited sanitary and management practices. No large, technological operations have had an outbreak. There were also cases in two zoos and at two technical schools. In every instance, the rabbits were euthanized, the premises sanitized, and no animals were allowed in or out for one to three months. Transporting rabbits or rabbit byproducts in Mexico currently is prohibited, as is the hunting of wild rabbits and hares.

The strategy of promoting biosecurity measures and rapidly isolating and containing cases as they cropped up served Mexico in the past. RHDV1 entered the country in the late 1980s via frozen rabbit meat from China. It spread to domestic rabbits in several states and took a few years to eliminate.

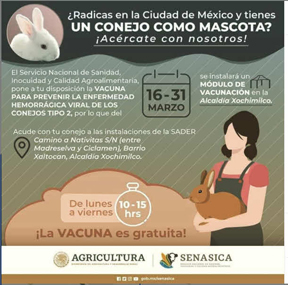

Mexico_vax_campaign

Screenshot of the National Advisory Technical Council for Animal Health Instagram page

Mexico's Ministry of Agriculture drove an ambitious effort to create and deploy a national RHDV2 vaccine in six months. The government spread the word on social media, with ads such as this one promoting a free vaccination clinic in Mexico City in March.

De la Fuente is proud of his country for having eradicated a major outbreak but notes that RHDV1 didn't pose as big a challenge as the current virus subtype.

Responding to RHDV2 required an additional big step, de la Fuente said: Because of the rising number of cases and the displacement of the problem toward the center of the country, where the majority of rabbit farms are located, the federal government saw a need to produce a national vaccine. European vaccines were considered out of reach for small producers. "They wouldn't be able to afford it," de la Fuente said. "So what we thought was, 'OK, we have the problem. It is spreading to wildlife. We need to stop it. We need to protect the industry somehow.' "

The vaccine was developed by technicians from the National Food Safety Quality and Health Service (SENASICA) and the National Producer of Veterinary Biologicals (PRONABIVE), both agencies of Mexico's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, which is comparable to the USDA.

The vaccine is made with inactivated virus from the livers of rabbits that died from RHDV2 in Mexico. "That means that this vaccine is made from the strains that are really circulating on the field," de la Fuente said. "We needed to use a vaccine that will be effective against the real problem."

He said the product has proven to provide full protection with no secondary effects on the health of the rabbits. "It has been a really, really good vaccine," he said.

The government has been providing free vaccines since January to pet owners, rabbit producers, veterinarians, clinics and pharmacies everywhere in the country, with a special emphasis on inoculating all domestic rabbits within a 10-kilometer radius of positive cases.

De la Fuente said he's hearing good news from regions that saw the first infections — from Northern Baja come reports that native rabbit populations are bouncing back. However, the government remains vigilant, he said: "We don't rely on that. We don't go to sleep."

Correction: The story has been updated to show that an isolated case of RHDV1 was identified in Pennsylvania in 2018.

July 6 update: RHDV2 has been confirmed in domestic rabbits at a single location in Cobb County, Georgia, according to the Georgia Department of Agriculture.

May 24 update: RHDV2 was diagnosed in a domestic rabbit in Custer County, South Dakota, on May 22, making it the first positive case in the state.

This story has been changed to include revised case numbers for Mexico.