Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

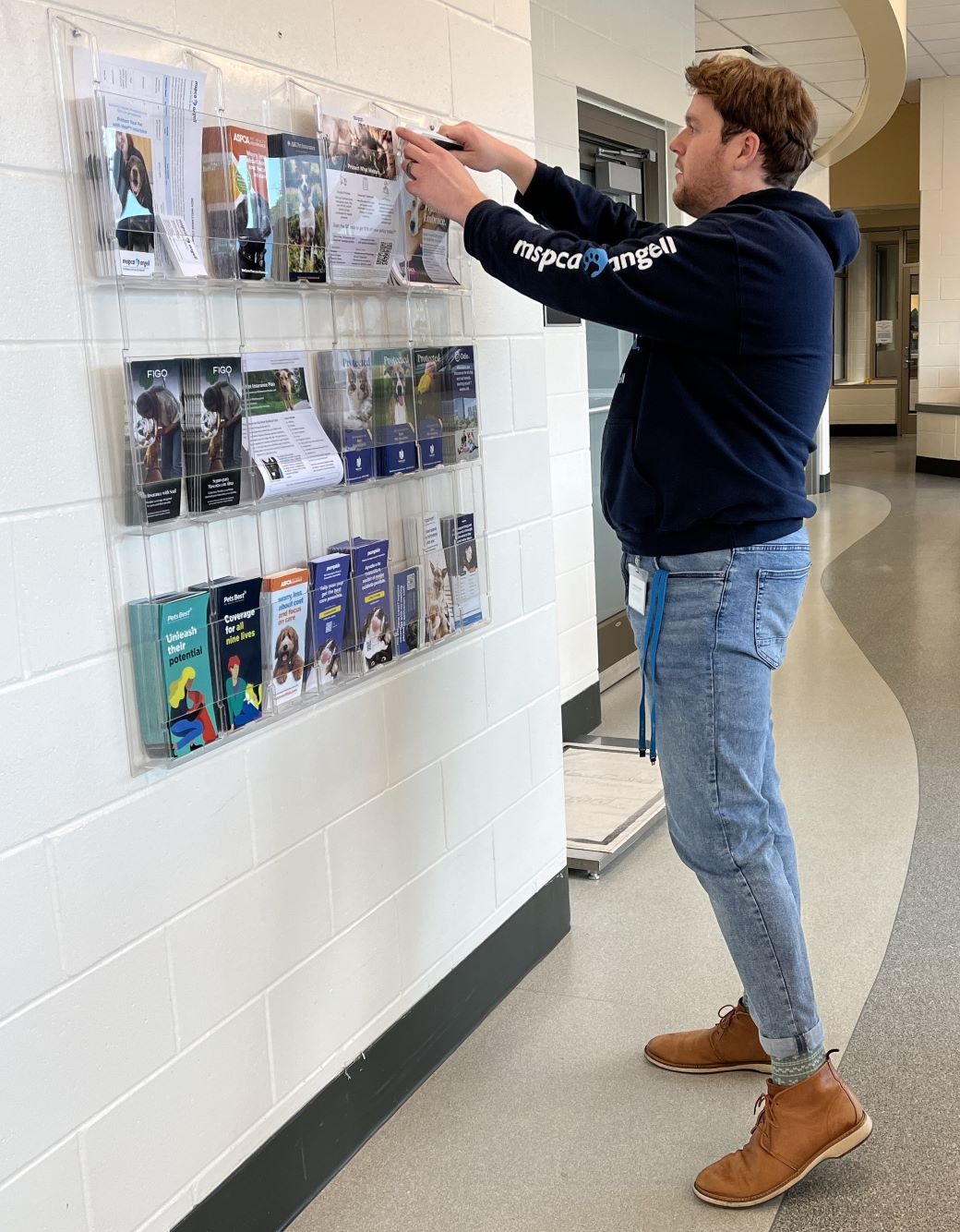

Harrison Stenson

Photo by Sara-Rose Brenner

Harrison Stenson, a full-time pet insurance coordinator at Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston, checks the stock of pet insurance brochures in the hospital lobby.

During a brainstorming session on how to help pet owners cope with the swiftly rising cost of veterinary care, this idea came to Dr. Ann Marie Greenleaf: How about dedicating a staff member to counsel clients through choosing and dealing with pet insurance?

As the chief of staff of Angell Animal Medical Center, a large nonprofit hospital in Boston, Greenleaf knew that the veterinarians were too busy and disinclined to field pet owners' many questions and periodic problems with insurance. Yet she wanted to offer an information resource as well as a means to help pet owners afford care.

From that concept, the role of an in-house pet insurance coordinator at Angell was born. Since July 2023, Harrison Stenson has been the go-to guy for pet owners wanting advice about insurance for their animal companions, whether it's choosing from among the 34 brands sold in Massachusetts, submitting a claim for in-patient care or appealing claim denials that appear unjustified.

"The vast majority of people are happy to get some help because it's super confusing," said Stenson, whose services are provided by Angell for free not only for its clients but to anyone in Massachusetts seeking guidance.

The bulk of Stenson's time is spent developing custom insurance recommendations for clients based on their needs, priorities and budgets. The hospital receives no commission or any other form of compensation from insurers. It aims to walk a line between promotion and support, with staffers asking clients whether they have pet insurance and offering information and assistance if desired.

"We're not pressuring [pet owners] to buy insurance, and there's no monetary benefit to our hospital if somebody purchases insurance," Greenleaf said. "We've had several of the insurance companies talk about giving back to the organization for every policy that comes from one of our recommendations, and we're like, 'Nope.' We don't want it to look even remotely like there's some kind of kickback."

A rarity among veterinary staff anywhere in the United States, Stenson is not, however, the first designated pet insurance expert in a practice. As a full-time staff member with state insurance adviser and producer licenses, though, he represents a new iteration of the role.

Coincidentally, another large, urban, nonprofit hospital established a similar staff position in 2023: Schwarzman Animal Medical Center of New York has a pet insurance coordinator who assists with claims submission and appeals and obtains pre-approvals when needed.

A smattering of veterinary practices long have had point people on their support staff to handle insurance queries but typically not full time. In 2015, Dr. Doug Kenney, host of the Pet Insurance Guide Podcast, interviewed two receptionists from a 24-hour emergency and primary care hospital in the Florida Keys whose jobs included advocating for pet insurance and fielding clients' questions on the subject.

That same year, Jennifer Abitino, a veterinary assistant at Heart of Chelsea Veterinary Group in New York City, suggested to her boss that someone be designated to handle insurance questions and troubleshooting. She offered to be that person. He agreed. Abitino initially absorbed the duties as part of her assistant job. Today, she serves full time as the pet insurance specialist, working remotely from home.

On-the-job learning

Angell is a large organization in Massachusetts with an emergency and specialty hospital, multiple primary care locations and animal shelters. The hospital in Boston has 85 doctors on its staff of 500. Greenleaf projects this year's patient visits will exceed 80,000.

Stenson came on in 2021 for a front-desk position, later working on the admitting and financial team before assuming the pet insurance coordinator job. He knew nothing of the subject at the time.

"I didn't know anybody with pet insurance," said Stenson, whose bachelor's degree is in music. "I was coming at it totally blank."

He read everything he could find online — product websites, comparison services and the like. "I started putting together a spreadsheet: What options are there, what do they cover, what do they not cover?"

He dug into sample policy documents and called insurance companies, talking to whomever was available, to get "a feel for the culture."

He learned where to look up the strength of each brand's underwriter, "just to make sure there's nothing fishy going on there. I would not want to recommend a policy with a poorly rated underwriter," Stenson said.

In the United States, selling insurance requires a state license. Although Stenson doesn't sell it, he became licensed so there would be no question about his qualifications in the field.

He discovered that the training and test required for licensing didn't reference a single thing about pet insurance. "It's really not on the radar of most property and casualty agents at all," Stenson said, referring to the category under which pet insurance falls — the same as houses and boats.

The awkward categorization of pet insurance is a big reason the field is confusing to consumers. Because it pertains to veterinary medical care, pet insurance would seem most analogous to private health insurance for people. But it's regulated differently. One key difference is that pre-existing conditions are not covered. There also may be waiting periods for coverage or exclusions for hereditary conditions.

Judging from message board discussions on the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service, many veterinarians take an arm's length approach to pet insurance, leaving pet owners to sort out on their own whether to buy it, which product to buy and how to submit claims.

Some practices avoid involvement for fear they'll be blamed if an insurer denies a claim.

"Knock on wood, to date, we haven't had anybody angry about the insurance that they purchased," said Greenleaf, Angell's chief of staff.

She noted that when Nationwide, the country's largest pet insurer, announced earlier this year that it would drop 100,000 policies, affected pet owners were upset, "but not at us."

Another concern of many veterinarians is that pet insurance companies may, like health insurers, gain enough power to dictate the cost of care.

Greenleaf believes the industry is a long way from being able to do that, with fewer than 4% of dogs and cats insured in the United States. The proportion is similar in Canada.

By comparison, about 30% of Angell's clients have insurance, she said, through a variety of carriers. "We don't promote one over the other. I feel like that gives us power," Greenleaf mused. She also noted, with a laugh, "We're pretty uptight. I don't want anybody from the outside to tell us how to do our business. ... So if an insurance company came in and said, 'Well, we want you to do this,' we'd be like, 'No. Why would we do that?' "

The worth of investing in a point person

Greenleaf said Angell's driving motivation in providing a point person on insurance is to help pet owners access care. "We want to position pet owners so they don't have to make life-and-death decisions [simply] because they can't afford it," she said.

At the same time, doctors have someone in-house to whom they can refer questions. "It just makes it more accessible to clients because we're not relying on the doctors being salespeople in the exam room, and they don't want to be," Greenleaf said.

Asked what it costs the organization to support a pet insurance coordinator full time, Greenleaf compared the pay to that of a hospital supervisor. In the Angell hierarchy, supervisors are the level between support staff and the manager of a particular service.

Abitino, the pet insurance specialist at Heart of Chelsea in New York City, noted that pet owners with insurance tend to avail themselves of veterinary care more readily, which increases practice revenues. "I've analyzed the amount of revenue brought in by insured clients, and it is greater than uninsured clients," she said — and the difference more than covers her salary.

Echoing Greenleaf, she said her goal is to help clients access care, and in a timely way. "It's not just the finances of it," she said. "It's, when your pet gets sick, you're not waiting three days to see if they get better before bringing them in."

Similar to Angell, Heart of Chelsea receives no compensation from pet insurers related to its advocacy of insurance, according to Abitino. Unlike Angell, the practice group does not recommend specific products.

"There's an extraordinary need for clients to have someone they can ask questions of who's not selling them a product," she said.

Abitino sees her role as providing information in plain English, much of it posted on the practice website, to help pet owners understand how pet insurance works. "Once you know how it works, then you can make an informed decision," she said. "There's not a one-size-fits-all that works for everyone."

She also submits claims for any client who'd like that assistance — a significant part of the job.

When Abitino became Heart of Chelsea's go-to insurance person, the practice had a single location. As of last week, it had four locations that together counted 50% of patients as insured. A fifth location opened this week.

Heart of Chelsea is also, today, part of a larger group of veterinary practices partially owned by a hospital network called Suveto. Abitino said the team at a hospital in Chicago recently told a Suveto district manager, "We have clients who are asking, and no one knows anything about insurance."

The manager put the hospital in contact with Abitino. On the day that she talked to the VIN News Service about her job as a pet insurance specialist, she'd spent an hour on the phone training a Chicago staff member to fill the same role.

Correction: This article has been changed to identify Stenson's insurance licensing more accurately.