Veterinary medicine is one of the most homogeneous professions in the U.S.: Nine out of 10 veterinarians in the country are white. Various efforts over the years to attract and support more people of color in the profession have yielded only modest results.

Veterinary medicine is one of the most homogeneous professions in the U.S.: Nine out of 10 veterinarians in the country are white. Various efforts over the years to attract and support more people of color in the profession have yielded only modest results.

Discontent with the lack of diversity gained new urgency this year, as protests over systemic racism erupted around the country, and the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately harmed communities of color. Professional organizations and associations announced new commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion. Individual veterinarians took stock, confronting bias and exploring systemic discrimination in blogs, for example.

To expand understanding of the profession's demographic challenge, the VIN News Service invited several Black veterinarians to talk about their experiences. We focused on Black veterinarians because their numbers in the profession are so small, they don't even register as a percentage of the profession in federal data: According to 2019 figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Blacks make up 0.0% of the occupation. By comparison, they comprise 13.4% of the total population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The veterinarians who agreed to share their perspectives for this article talked about what drew them to veterinary medicine and what they experienced in school and in the workplace, offering candid snapshots from the trenches. They also talked about their hopes for the future and offered suggestions for better diversifying the profession.

What follows is a condensed, edited version of a Nov. 15 Zoom conversation hosted by VIN News. The 84-minute discussion is available as a video. It includes more stories that might surprise, amuse and inspire listeners.

Tell us about yourself and what drew you to veterinary medicine.

Dr. Niccole Bruno, chief of staff of Companion Animal Hospital, a VetCor-owned practice in Spring, Texas: I was born and raised in Queens, New York. I grew up in an apartment, and we couldn't have pets. There were a lot of stray animals in the neighborhood. When I would see them, I would cry, knowing they were hungry. So I started buying food at the bodega, and I would feed them. I had a little parade of pets following me. But it was OK, because I was making them feel better. I knew I loved animals. I wanted to be a doctor. I just kind of combined the two and said, "I'm going to be a veterinarian," and that was at the age of 12.

Because I work for a corporation, I'm very quickly realizing how there is a lack of diversity not just amongst us but even in leadership roles in the industry. So I have been having dialogue with the corporate suite to identify a [chief diversity officer] role but also to start a diversity, equity and inclusion task force at VetCor over the summer. We've been working to implement programming for K through 12, vet-school level, and college level and beyond. I'm excited about those opportunities, but we are just getting started as a corporation in that.

Dr. Will Draper, multi-practice co-owner and CEO, The Village Vets in Atlanta: I practice small animal medicine in Atlanta. I graduated from Tuskegee University's School of Veterinary Medicine in 1991. My mother is from Tuskegee. Both my parents are from Alabama. My great grandmother went to Tuskegee; my grandparents went to Tuskegee; my maternal grandparents lived in Tuskegee. So I would visit Tuskegee very often when I was young to visit family. I grew up in Inglewood, California. My father graduated from Tuskegee with an engineering degree. I wanted to be an engineer because my father was an engineer. When I was about 11 … he said, "So I've been thinking about this, you know, to be an engineer you have to be very, very proficient in math and you are not. So you need to think of something else to do," and kind of crushed me. I said, "Can I be an architect?" He said, "No, you can't be an architect." My father was very real with that. He said, "But you love animals."

I've thanked him many times for being honest with me because I'd be a horrible and miserable engineer, otherwise. And I wouldn't have met my wife [who is also a veterinarian], which got me into this wonderful situation I'm in.

I'm trying to do an "anti-corporate thing" to give students coming out of school and young veterinarians an opportunity to get into a practice as a managing owner and partner and have their own practice without having to figure out how to finance it, with the support of my group The Village Vets. The group's called SUVETO, Supporting Veterinary Ownership. I am focusing a lot — and have no shame in it — on minorities, particularly a lot of those from Tuskegee … [to] help them understand that they can do this and why they can do this. Because, even today … there are still people who have seen me, and I'm the first Black male veterinarian they've seen.

If we don't make the change, change is not going to happen. We have to be methodical about it, and thoughtful. And we have to be a little selfish. The last five veterinarians I've hired, four of them are African American. There is a reason for that. I want to give them opportunities, and they want the opportunities. I should not be ashamed of bringing Tuskegee grads in, just like University of Georgia veterinarians hire University of Georgia graduates.

Dr. Hindatu Mohammed, owner/practitioner, Allandale Veterinary Clinic in Austin, Texas: I was born in Nigeria but moved to Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, when I was 3 years old. My father actually, like a lot of Nigerians at that time, had come to this country to study. He was getting a PhD at the University of Pittsburgh.

Like Niccole, I wanted to be a doctor when I was younger because my dad said, "You should be a doctor." And I said, "OK."

I had a very formative experience with an ant when I was young. I was outside playing in the yard and just playing in the dirt and digging up stuff, and I came across this ant that I had unwittingly dismembered. I remember trying to put it back together and, of course, it was a disaster. In that moment, I felt this overwhelming sense of obligation to take care of this living creature that couldn't take care of itself. That was really the light that went on up in my head, that animals need people to advocate for them because they cannot advocate for themselves.

That idea just came from that, because we never had animals growing up. I tried for years and years and years to get my family to have a dog and they were just, "No. No. No." It wasn't coming from experience of having pets in the house. It was really coming from this experience of being a compassionate person, and really feeling a sense of responsibility and duty to others that were less powerful. Once the idea came in my head, it didn't leave.

I went to Cornell for undergrad, and the idea of going directly into vet school was really difficult for me to imagine because I had so much debt. I felt vet school was something that I could do later if I wanted to, but I really needed to try to figure out how to make some money. I taught for four years between undergrad and vet school, and I'm really glad and happy to have that experience because it's shaped so much of my career as a veterinarian.

I have a soft spot in my heart for other students like myself who took some time off and had second careers and what have you. Some people decide to be a veterinarian when they're a kid, and they just go straight through, and other people don't … because they can't afford to. Other people don't because they weren't exposed to it and didn't even know that it is an option. For me, a lot of this discussion of inclusivity is really bringing in these people with different experiences that don't necessarily all look like the cookie-cutter veterinary student might look.

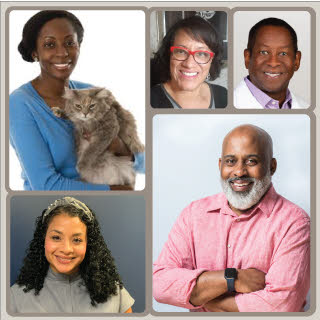

Donna Jarrell

Photo courtesy Dr. Donna Matthews Jarrell

Dr. Donna Matthews Jarrell is attending veterinarian and director for the Center for Comparative Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown. In her diversity, equity and inclusion work, she deploys lessons learned from the General Management Program at the Harvard Business School. She was one of only four women out of 64 students in her 2006 class.

Dr. Donna Jarrell, attending veterinarian and director, Center for Comparative Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital in Charlestown, Massachusetts: I am a 1988 graduate of North Carolina State's College of Veterinary Medicine. That means that I was the second African American to attend the school, and the first African American female to graduate. I am grateful that the doors stayed open, and there's tons and tons of African American females coming out of NC State now. So I'm very excited by that.

My main influence was from my father. He grew up on a farm in eastern North Carolina. I am from Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He worked in veterinary practices in the summers. I was fortunate enough to tag along with him. So that was really where I got exposed to veterinary medicine.

The love came really through a formative event in my life. I had a young house dog who got hit by a car and required about six or seven months of extensive care. [I] was told that he had a 50/50 chance of walking. But I was able to patiently get him back to full ambulation. And that experience by itself told me that I had the skills to do this, and so it became something that I was focused on.

When I turned 16, on my birthday, I went and interviewed at several veterinary hospitals in my hometown, saying, "I want to go to vet school. I want to get experience." There were no Black vets in my hometown. So the first person who hired me, of course, was a white veterinarian, who after a couple of years told me I'd be a great technician: "You really are pretty smart; you're going to be a great technician."

What really sealed the deal for me is that he sold his practice to a Black Tuskegee graduate who was moving back home, who was Dr. Calvert Jeffers Jr. He literally walked into the practice that I was working in, and then everything changed.

I got out of vet school, immediately went to the NIH. I will say, graduating in the late '80s, the non-practice career options were really becoming a new avenue. The lab animal veterinary community was just growing because the regulatory agencies overseeing that created more requirements around having a veterinarian employed in your programs. I was working in research while in vet school. And so, a way to combine my continued interest in research with clinical responsibilities was laboratory animal medicine.

I've been in the industry now for over 30 years, so us long-timers are hanging in there. What I'd say I'm most proud of right now is that last month, I assumed the role of president of the American College of Animal Laboratory Medicine. I am the 10th woman, the 61st president and the second African American. So, timing is everything. I intend to make diversity, equity, inclusion a key part of our platform for the year, and lucky for us, we're doing a strategic planning event at the end of this year, so we'll be incorporating that into our strategy as well.

George Robinson

Photo courtesy Dr. George Robinson

Dr. George Robinson is founder and vice-chair of Heartland Veterinary Partners, a Chicago-based consolidator with more than 150 practices. Robinson had his own practice in New Orleans for many years, and held operational and management roles at National Veterinary Associates and Banfield Pet Hospital.

Dr. George Robinson, founder and vice chair, Heartland Veterinary Partners in Chicago: I've been in the mix for quite a while. I'm an '81 graduate of LSU [Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine]. My career is so varied, it's unbelievable, but primarily I've been a practitioner. I got into the corporate world by hook and crook, and ended up starting a company called Heartland Veterinary Partners. We're a consolidator of veterinary practices, private-equity based. In June 2016, we started with one practice and a philosophy and culture that I worked tirelessly to create. Now we're way north of 150 practices. It's a big corporation, and as of last month, I decided to take a break and move to vice chairman of the board of directors. Now I'm no longer the CEO, and actually it's a sigh of relief because it's a tremendous responsibility running a business that big and having all those people that are under your purview. It's been fun.

I was really blessed. My father was the dean of the College of Agriculture [at] Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, so I'd been exposed to academia. I'd been exposed to animals. And my dad mentioned every blue moon that he always kind of wanted to be a veterinarian but the opportunities weren't available back when he graduated. He actually went to the University of Illinois for his PhD.

So he kind of was happy that I leaned that way. But even more importantly, there was a Tuskegee veterinarian, Dr. Clyde Raby. He practiced in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Great, great guy. He was a mentor to me. When I decided I was interested, he kind of pushed me and guided me and gave me direction as to what it would be like to be a veterinarian Down South, in particular. I really appreciated that.

I made my decision at 14, like most people.

When did you meet your first Black veterinarian and was it significant for you?

Draper: Very soon after my father took me over to the veterinary school when I was about 11 … he took me to meet the first Black male veterinarian I'd ever met, [Dr.] Jerome Williams, who actually still practices now, and I still see and talk to [him] from time to time. That was something I remember liking. Some summers, I'd go over there and spend some time with him and hang out in the kennel and things like that. Really, the closest thing I had to an experience working in a veterinary practice before vet school was that, because there were really no veterinarians in Inglewood, California, where I grew up.

Robinson: Meeting Black veterinarians … what it does, it introduces possibilities. You believe that, well, if he can do it, I can do it, too. It makes it more tangible. But even more than that is the mentorship … just to be able to talk to someone is a very positive influence.

Mohammed: The first Black veterinarian that I met was actually the aunt of a classmate of mine in college, so it wasn't until probably junior year. It was hugely impactful, not only because she was this Black veterinarian who was also a business owner, but also because at that time in my life … I was sort of really intimidated not just by all the debt but also by just the culture of the pre-vet life. It was a really super competitive, very cutthroat environment. I felt like, I'm here just because I love science and the animals, and the environment was really off-putting to me. I was at this period of time where I thought, well, I'm probably not gonna apply to vet school right away and maybe I won't apply at all, who knows? I mentioned to her that I'd been thinking about going to vet school but wasn't sure if I was going to get in. And she was very much like, "No, not only are you going to apply, but you're going to get in, you're going to do it." She basically said to me, "Who am I going to leave my legacy to?" And that was huge, because no one else had said anything like that to me at that time. I've never forgotten to this day.

Jarrell: The experience that I had of actually being in a practice as a kennel assistant trying to learn along the way, being the only Black in the whole practice, and just constantly asking for and being given more and more responsibility, was what I was pursuing. But it wasn't as if mentorship was being offered; it was being earned. When Calvert Jeffers bought the practice, that changed everything. Mentorship became a part of the job, it became exposure, education: "Let's look at what we're doing. Come in here, and let me show you how to do this." That came as I was transitioning into my undergraduate years, so it really gave me confidence.

Bruno: I listen to these stories, and I'm all nostalgic because I didn't really have mentorship at all. I had to find my hours working with white male veterinarians. I always felt like I had to over-perform in order for me to get into the exam room to get the shot, the experience of drawing up the vaccination. Nobody really explained things to me.

Now that I'm on the other side, I've always made a point to mentor students and not just let them shadow me, but continue the conversation. You know, check in on them, email, text messaging: "How are you doing?" I have a couple of students I've seen through, and they're on the other side. And that makes me feel good because I didn't have that.

What were your veterinary school experiences like, from applying to attending?

Will Draper

Photo by Hector Amador/Amador Photo

Dr. William Draper is co-owner and CEO of The Village Vets, which has five locations in the Atlanta metro area and one in Pennsylvania. With his wife, Dr. Francoise Tyler, Draper is featured on the Nat Geo WILD-produced television series, Love & Vets.

Draper: It's interesting seeing Dr. Jarrell and Dr. Robinson because I just assumed that Tuskegee was the only place that I could go, so that's where I applied. I applied after my junior [year] with the expectation that I wasn't going to get in. And then I got in. I was 20 years old, and I struggled that first year because I'd be taking a test and I'd hear everybody out at the homecoming parade.

I was a SCAVMA [a chapter of SAVMA, the Student American Veterinary Medical Association] rep and I remember going to one of the meetings. Typically, the only two Black students were the Tuskegee students. I remember there was a Black veterinary student from, I think, Arkansas [or] Oklahoma, and I just couldn't even believe it. I said, "What even made you apply to school there? I didn't even know that I could do that."

At the time we were courting, I would go see [my wife] at UGA [University of Georgia]. I just walked down the hall and looked at all the pictures of the classes. About '89 or '90, you'd start seeing one Black person here, and there'd be one Black person there. It was almost intentional, every other year, "OK, we got to throw somebody a bone here, so that we are checking all the boxes."

Jarrell: I was a SCAVMA rep as well from NC State. When I went into the meeting, all the Tuskegee guys were shocked to see me as well, and I was so happy to see them. Can I just tell you, there's a camaraderie, regardless of where you went to vet school, that you know your roots come from Tuskegee. I always acknowledge that I'm happy that I have that network, the Tuskegee alumni network, available to me.

I would say for me, the hardest part of getting into vet school was trying to meet the criteria to get the interview because you had to have everything tight — your GPA, your experience, your standardized testing scores — to even be considered for an interview.

I was fortunate to work at the vet school, prior to applying. My last couple years of undergraduate … I got to go into toxicology laboratory and helped set it up. I really, really, really believe in my heart that the fact that the faculty knew me, knew that I was there at the school prior to applying, actually put a face to that package that they were looking at. I think that was really, really important for them to offer me the interview. Once I got the interview, my passion showed.

Robinson: My story is a little bit different. I was the first African American from Louisiana to get into a Louisiana veterinary school. My whole experience through veterinary school was, I would say, a little short of Bizarro World because every conversation had race involved, and that gets on your nerves after a while. I endured and thrived and did really well because I'm just, I think it's just my personality. If I did not have that kind of personality, I would have really suffered in veterinary school.

I have to give one quick commercial for any of my mentees who may be listening to this. I had a lot of students that came through my practice in New Orleans. I practiced there for a long time. They thought I was pretty tough. But I have to say that of those students, I have 13 of my mentees who came through my practice who are veterinarians, so I'm really proud of that.

Hindatu Mohammed

Photo courtesy Dr. Hindatu Mohammed

Dr. Hindatu Mohammed owns Allandale Veterinary Clinic in Austin, Texas. Before attending veterinary school at Cornell University, she spent four years teaching everything from sixth-grade math to first-grade drama. She said the experience helped her in school and beyond, and she hopes veterinary school admissions boards will do more to value life experience.

Mohammed: I think I mentioned, you know, for me, financial was a big [obstacle]. Just knowing I was going to be coming out of college with so much debt and then getting even more debt in vet school.

But I do want to say — because Dr. Jarrell brought this up about your experiences as an undergrad helping you — I went to Cornell for undergrad and I worked ... as a work-study student in an FIV [feline immunodeficiency virus] laboratory, Dr. Roger Avery's FIV laboratory.

Working in that laboratory and getting that experience for several years I'm sure helped me get into vet school. I bring that up to say that while, of course, there's not a lot of mentorship opportunities with people that look like us, it's really important for anyone listening to this to realize that you can be a mentor to any person of color without being a person of color. So this was a British veterinarian who employed [me] in his laboratory, wrote a recommendation for me, allowed me to do an independent research project — all these things helped me distinguish myself in applications.

When I was growing up in Pittsburgh, I didn't see any Black veterinarians, but I called up white veterinarians and said, "Hey, can I come to your practice?" And they said yes. It's super important. Of course, would it have been even more impactful for me to see a veterinarian who looked like me? Absolutely. But I wouldn't be here were it not for the support of veterinarians, period, who saw something in me that they thought was, you know, was worthwhile and worth supporting. That was a huge, huge deal for me.

Bruno: For myself, I don't think I had any real obstacles getting into the veterinary school. I knew what I needed to get done, and I put in the work and the time. I was fortunate because Tuskegee had career days, and there [were] companies that came to recruit, so I had the experiences, I had the GPA. I felt confident.

When my mom suggested to me to apply to Cornell, I was like, "For what? Because I'm going to stay at Tuskegee." She's like, "Well, don't put all your eggs in one basket. Cornell's your state school." So I applied, and when I got accepted, I was kind of like, "Whoa." One, I was excited because I knew I was going to be a veterinarian, regardless. But, two, I was a bit scared because now I had gotten comfortable being around people that looked like me.

[During a Cornell campus visit], I'm looking around and there was only one other person of color. I'm like, "Here we go. Is this what I want?" Cornell's director of academic affairs is Dr. Jai Sweet. She's Indian. She approached me, and she said, "I know that you're having reservations about leaving Tuskegee to come to Cornell, and I can understand that. Just know that we are really trying our hardest with recruitment, and I hope you give us a chance." Her acknowledging that without me having to say it, it spoke volumes to me. It was like she saw me, she saw what I was conflicted with. And so, I ultimately decided to go to Cornell. I have no regrets.

Dr. Sweet was right. My class today has the most ethnic diversity of Cornell's history. I don't know if any of you are familiar with the student organization VOICE, but that organization was founded at Cornell by my classmates. It stood for Veterinary Students as One in Color and Ethnicity. [The group now is Veterinarians as One Inclusive Community for Empowerment.] Because we had each other, and because it was our goal to change the environment of Cornell's campus and Cornell supported that … we were able to make some big changes at Cornell. Now VOICE is a national organization and has corporate funding. So it can be done. It's just a matter of being intentional with how we choose to recruit students of color.

What was it like for you to be in situations where you were the only Black veterinarian? How did you support yourself? How did workplaces make you feel included or excluded?

Robinson: I created a committee of one. My determination was, before I leave this profession, there's going to be a whole lot more Black veterinarians. So everything that I've done in different activities has been to encourage, mentor, inspire, push more minorities, African Americans in particular, to become veterinarians.

The other thing is creating acceptance. I went through this whole thing when every time I talked to somebody in Louisiana, they had to mention "By the way, you're Black," or some kind of little paper cut. I try to create that kind of environment in my interactions with folks to say, "Hey, enough of that. Let's treat everybody equally." Be receptive. Be empathetic. Be positive about the relationship, and not necessarily focus so much on the person's race.

That's been a big push for me in my whole career to try to remind the profession that we're way behind eight balls as far as valuing diversity. If we can improve that alone, we'll be miles ahead. In the past, I've walked into all these different environments, and they don't value diversity. They don't even see the reason why any of this needs to be discussed. So in my one-on-ones and in my committees and things like that, I push to get people to say, "I understand that there's a need."

We have to reach out and, you know, students aren't going to passively just say, "Oh, you know because you're there, we want to be a part of you." You have to reach out and say, "If you come in, you're welcome. You'll be included. Come join this party."

Jarrell: I was fortunate enough in my early years to become a Commissioned Corps officer in the Public Health Service and spent 10 years at the NIH [National Institutes of Health]. I remember I was a student extern spending the summer there, and I met with the chief veterinary officer of the Public Health Service. He said, "Well, you know we only offer one or two entry-level jobs every year in the Public Health Service." And I said, "That's great because I only want one of them."

And that was that promotion of, "I want to be there, I want to be present, I want this opportunity. Whatever your motivation is to consider me, I'm ready."

Today, my department's about 120 people. We support a research program at Mass General Hospital that's over a billion dollars. [It's a] very large place, and I'm still one or two walking in the room. They assume I'm an admin when I walk in the room. It's just so many little things that I feel it's time to call out. It's time to talk about race from a standpoint of value, from a standpoint of creativity, from a standpoint of strengthening your program. Regardless of the past, now is the time … to stop soft-shoeing this and call it out.

I tell my frontline staff, which is all white, right now — and I say right now — this is part of our conversation and part of our culture. We're going to talk about the hiring, we're going to talk about the training, we're going to look at the data, we're going to prep our frontline staff to understand their biases.

I have them doing mindfulness activities because it's been proven if you practice mindfulness, it opens up your mind to understanding race a little differently. It's time. It's time to think differently about the value of diversity and equity.

Draper: I had a client, years ago, who said he didn't want his dog to see colored people. I could have told him to leave, but I said, "Look … your dog needs help, and I'm going to take care of your dog." He ended up being, you know, one of my best clients. He stopped calling me "the colored doctor" after a while and he started calling me "Doc."

And when it was time to put his dog down, I was the one that he called to do it because, you know, we just had to have that conversation. Sometimes, you have to understand where people come from, and what you've been taught.

I understand that sometimes, you got to have those uncomfortable conversations and you can't just walk away and throw a bird up and say, "OK, well, you know, screw them." You gotta go back and say, "Look that's not cool. You can't do that." That's how we just get a little bit better and better in our profession, and really, in this kind of insane world we live in.

Robinson: I used to deal with "My pet doesn't like people of color," all the time. And I would remind some of my clients, "You know, animals don't see in color." And they look at me like, "I don't believe it." But I dealt with that all the time. It was crazy.

In questions emailed to participants before the meeting, VIN News asked, "Do you find there are things that your peers who are not Black don't understand about your experience?" Mohammed reflected on that question.

Mohammed: It's all this that we're talking about. It's like, if somebody has an issue with your medicine, is it because they don't like your medicine? Is it because, for me, I'm a woman? Or was it because, at the time, I was a younger woman? Or was it because you're Black? You're always having to question that. There's that constant burden of always having to second-guess yourself. It requires a tremendous amount of confidence and belief in yourself because sometimes you're the only one that does believe in yourself.

I have recently really focused my efforts on the outreach to younger veterinarians or to students and specifically, you know, unapologetically now being like: I am offering an internship for people of color in my practice. I'm targeting females of color interested in veterinary medicine. I want to model that. I want to model practice ownership. So reaching out to high schools in the area and saying, "Listen, I want your Black and brown students." Previously, I would have felt sort of bad saying that and limiting that opportunity, but I'm really acutely aware of not only limited opportunities for people like us, but also the power of it coming from someone that looks like me.

Jarrell: You know, Hindatu, you talked about feeling bad about that, but I just had a conversation with my team the other day, and I showed them the unemployment statistics. I said, "When you talk about 6% unemployment, please know that is for whites. I said for us, it's 11½–12%. So if you want to do something to help address economic disparity, then pick the person of color, if you have candidates. That's your justification."

Do you feel the profession is changing?

Niccole Bruno

Photo courtesy of Dr. Niccole Bruno

Dr. Niccole Bruno is chief of staff at Companion Animal Hospital in Spring, Texas, one of more than 400 practices owned by VetCor. She provides mentorship opportunities to students at historically Black colleges and universities (known as H.B.C.U.s) and veterinary schools across the country.

Bruno: I can't say it hasn't changed at all, but I think that the growth of it has definitely been slim. I mean we all are coming from different generations of veterinary medicine, and we all have, if not the same story, a different version of it.

The problem is that a lot of the efforts have been on the front end. "Let's mentor, let's get these students of color into the industry, let's support them through vet school." And then when they graduate, and they are coming into the other side of it, the professional side of it I don't think has changed much. It's because you've got a subset of privately owned practices who have been able to maintain their culture of hiring the same types of individuals. You know, nobody puts out ads. If somebody's leaving, it's like, "Who do you know?" "Oh, you know, my sister's daughter or …" It just kind of brings the same kind of people that are coming into the hospital and maintaining that culture.

I moved from New York to Texas 3½ years ago, and I started working at a practice where I was the only person of color. I was used to that even in New York, but at least in New York, every now and then, you would have a staff member that was a person of color. But here, I was the only one. Everything came to head when I was given the role of chief of staff, and within four or five months, the entire staff left. I had to start over again, hiring, rebuilding. In the midst of it, that was terrible. As a leader, I doubted myself. I was practicing good medicine. I was practicing good practice strategy. But I think they [the staff] had a problem hearing it from me.

So I was able to hire staff that I could build. A lot of times when I look at hiring, I don't just look at vet experience. I look at other skill sets. I'm in Houston, we have a heavy Latino community. I'm not fluent in Spanish. I hired people that can speak Spanish, and that ultimately breeds the culture of inclusivity in the workplace. You can make changes that way.

We have to be much more intentional about making sure that this profession is inclusive. Right now, they have CE [continuing education] requirements. Why don't we have requirements on diversity training? That's an easy way to get the profession on board. Things are constantly evolving in this profession and in the world of diversity, so why not make that a requirement? I think that if we can be more intentional about those demands, then I think we're heading in the right direction.

Robinson: My perception is that veterinary medicine is just starting to talk the talk, but we still haven't figured out how to walk the walk. We haven't figured out how to make a lot of lip service tangible. That's one of the challenges AVMA [American Veterinary Medical Association] and all the constituent organizations have to figure out. Take it beyond talking.

After we do all of this, like every decade, nothing happens. Because it has to be a lot more, as someone said, intentional. That's where we need to depend upon these larger organizations to help facilitate that and make it happen. We're not there, and I don't think in many cases if we even know how or we're prepared to do what it takes to make these things happen.

Jarrell: I would add to that, I think we don't have a real appreciation of the value of diversity in the veterinary profession at all. And so, it's kind of a passive thing. We're mindful, and we have a few mentors in the schools and along the way to help you navigate this, but the majority of us are OK to kind of sit on the sidelines. I found it really interesting how we just don't even have the data on who we are as a profession.

For me, we've got to make sure that conversation continues, as much as maybe people would like for these conversations to come to some sort of finite action or conclusion. It's not even time. We need to keep talking, and we need to keep exposing why … students of color struggle in the vet school setting when everyone thinks they've provided all these resources. But you've got attitudes of the students to deal with. If the school calls it out and says, "This is unacceptable," then you change the dynamics of your student population. [After the discussion, Jarrell clarified: "The culture has to resonate from the leadership, through the faculty and into the fellow students. A lot of times the students are allowed to get away with microaggressions, which can easily isolate students of color."]

Mohammed: So many people don't even believe the necessity of … supporting a more diverse population within the veterinary schools. Specifically, the issue people have is giving support and resources to people, and feeling this idea of equality versus equity. The reality of the situation is that when you support the people in your community that have the most need, then everyone benefits. The stress, the debt, all of these issues that veterinarians of all colors and genders suffer from, when we can create a profession that is more inclusive, that is more supportive of everyone, everyone benefits from that. But you have to believe that first; you have to view it from that lens of making the profession better, not from this lens of giving people unfair advantages or whatever narrative people want to subscribe to.

Bruno: I am going to bring up a point that I heard from Dr. Lisa Greenhill [senior director for institutional research and diversity, Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges] in a podcast she did. She mentioned how sometimes, the vet schools need to look into the applicant themselves. Like, yes, they may not have the highest GPA, but look, they may have worked two, three jobs to get themselves through school.

You want that resiliency … and that sometimes comes from students of color. We've had to dream bigger in this profession because when you Google "veterinary medicine," you don't see us. We have to see past that vision of the white doctor taking care of the animal to know that we can achieve it.

I've had conversations with Cornell. Cornell prides themselves on case-based learning. How can we include diversity in the curriculum of the program? From jump, in Cornell, you're presented a case on the respiratory system, but it's presented as "Six-year-old female spayed domestic shorthair presents to companion animal hospital for dyspnea." But what if it was: "That cat was owned by a biracial couple," or "That cat was owned by lesbians." What if we incorporated how we practice veterinary medicine to be inclusive of how we have that dialogue with the owners. What if they had socioeconomic issues, like, how would you bring up lack of money? How do we provide care? I mean, it has to be intentional how we build this — these words, this language — into the structure of veterinary medicine, because if not, we're just preaching to the choir.

Mohammed: This year, I was fortunate to be selected to read applications for Cornell. I barely look at people's grades because I'm not interested in your grades. I want to know what other people who work with you have said about you. I want to know what you have done. I want to know what struggles you've encountered. I want to know if you even know what this industry is about. None of that's reflected to me in what grade you got in biology.

All of us went to school with someone who was brilliant and couldn't talk to a person to save their life [and] had no bedside manner. There are some things you cannot teach. You cannot teach someone life experiences. You can't teach them basic compassion, hard work, all these things that don't necessarily reflect in your grades.

I'm really happy Cornell this year also decided to stop accepting GRE [Graduate Record Examinations] scores. So when we talk about, are things changing? I think they are changing — ever so slowly, ever, ever, ever so slowly. Would I like them to change faster? Absolutely. But I think that the change is coming. I hope it's going to be in our lifetime.

What have we missed? What does the profession need to think about going forward?

Mohammed: I was trying to think about the people that are going to come to this talk kicking and screaming. The point I always try to make to them … comes back to this idea of thinking of what supports you benefited from on your journey to veterinary medicine. I think some people would like to think of themselves as being self-made. I always challenge those people to think about what privileges you had that you weren't even aware of having. Did you work in the summertime at the clinic that your dad's golf buddy owned? Did you see a veterinarian that looked like you? That is a privilege, my friend. That is something that has allowed you from a young age to really believe in your ability to do this. I think really, really challenging people to think about their own privileges, and then take that mentality of turning back and pulling up the person behind you.

So, OK, you have achieved this position, what is your legacy? Is your legacy going to be fixing animals? That's a wonderful legacy, but there's got to be more to that. What can you as a person, not necessarily a person of color, but really, any person in this profession, do to bring and support the future of this industry that you love and care about?

Robinson: I want to thank VIN [Veterinary Information Network] for the opportunity to have this forum. I would call it a subset, but there are many more forums that need to occur, with even a more diverse group among us. These snippets of information and perspective can be a positive for the profession. It's a small step, but it certainly is important that this kind of conversation is available to the veterinary community at large. But not just to stop at this one conversation, but to observe all the various conversations that hopefully VIN will have and sponsor and learn from.

At the end of the day, Nirvana for me is that we value diversity, and everybody gets a chance to do their thing.

Jarrell: For us, who have to hold that door open, it's a lot of effort to be recognized and to make sure that people appreciate [the] diversity that you bring to the table. For me, the ultimate employee engagement is about full inclusion. So everybody has a voice, all the voices of diverse experiences that come to the table. And when you problem-solve, or when you operate with that kind of engagement and strength, you will always be better than you would if you were monolithic.

If your leadership tells you that that's the platform of the culture, that's great. But if they don't, you still have a team you rely on, and you can still do whatever you need to do at the local level to diversify, and then everybody gets what they need to be successful. And then everybody's voice is heard. That's really basic employee engagement. Any kind of agile organization is based on those basic things of employee engagement. That's what I would say is going to help us move forward.

Bruno: It can be very overwhelming on just where to begin. I think it's just important to start somewhere. Everybody's at different phases of this journey … whether they've accepted it, or whether they now need to become more aware of the resources, or what they can do, and who to surround themselves with, but it is important to just start because if you're doing nothing, we're going to continue being in the same place.

I also think that it's hard to always be the person to have to explain the emotional part of DEI [diversity, equity, inclusion] work, because we live it. It is important that our white colleagues take the time to self-educate and reflect and see where they are in this journey, because it isn't our job to educate. It's our job to, at this point, come to the table with everybody having a voice … but if we're constantly having to explain why this needs to be done, that is exhausting.

I am hopeful, because I think that we're at a point now where people are tired of being quiet, and it's always great to hear that there's people in all facets of veterinary medicine that are doing the work. It encourages me, like, "Keep going, Niccole." I have to remind myself sometimes because I shoot for the stars, but sometimes you got to just be happy floating in the clouds, you know, because you're still getting there.