Natasha Prentiss

Photo courtesy of Natasha Prentiss

Natasha Prentiss anticipates graduating debt-free in 2023 from Louisiana State University. Nearly 17% of U.S. veterinary students who graduated in 2020 reported having no student debt.

This is the third of three parts.

Like many of her classmates, Natasha Prentiss had a lifelong dream of becoming a veterinarian. The 24-year-old Oklahoman recalls being asked as a child what she wanted to be when she grew up. "I promptly and without hesitation answered that I wanted to be a dog," she said. "A veterinarian was as close as I was going to get."

Unlike many of her classmates, Prentiss didn't stress about the cost of education, although she did consider it, when she applied in 2019 to veterinary school. Accepted to five programs, she chose Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, where she now is in her third year. Asked how much she's spent on her degree thus far, she paused.

"My parents usually handle it," she said.

Prentiss says her father, a global engineering manager for Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, and her mother, a real estate agent, agreed to pay her veterinary school tuition if it cost around the same as her in-state option at Oklahoma State University. The family has since relocated to Canton, Ohio. "At the time, it was $79,000 for four years, and the cost of living was super cheap," she said of Oklahoma's program.

LSU provided an out-of-state tuition waiver and a one-time Dean's Circle scholarship of $15,000 for an essay she wrote on diversity, putting the cost to Prentiss in the same ballpark as Oklahoma State veterinary tuition. "It was the only scholarship of its kind that LSU offered," she said. "I was extremely blessed."

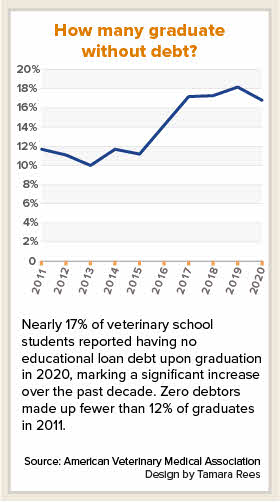

Her ability to pay upfront, without the help of loans, makes Prentiss part of a faction of seemingly affluent students that's grown in size among the nation's veterinary programs, even as overall tuition costs and indebtedness climb. During the past decade, the proportion of veterinary school graduates who paid for their education outright grew from just shy of 12% in 2011 to nearly 17% in 2020, according to surveys of fourth-year students conducted annually by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Colloquially, they're known as veterinary academia's "zero debtors."

The same AVMA survey shows six-figure student debt to be the norm among new veterinarians, with 2020 graduates borrowing an average of $188,853 to pay for their veterinary educations. While many survey respondents reported owing less, some amassed student loans greater than $350,000, and as much as $500,000.

At the nation's 33 veterinary schools, the cost of education isn't getting cheaper. In the same decade that the proportion of zero debtors grew, tuition and fees for veterinary education in the U.S. overall increased more than twice the rate of inflation, with resident tuition up more than 38% from 2011 to 2020, and nonresident (including private school) tuition up more than 31%.

If the trend continues, the profession may become disproportionately populated by those fortunate enough to come from wealth, Bridgette Bain, associate director of analytics for the AVMA Veterinary Economics Division, predicted during a recent online forum on how debt is changing the face of the profession.

AVMA research shows that parental financial support has a greater impact on overall debt levels than scholarships and grants, she said, warning that veterinary medicine might soon be a place "where only those who can afford to have their family pay for veterinary school are going to come into the profession."

The growing financial divide between students has created two distinct groups — those with no debt and those with seemingly insurmountable debt, $400,000 or more, according to Michael Dicks, former director of the AVMA Veterinary Economics Division. He's warned for years that veterinary academia is on track to price out everyone but the wealthy, and during an economic summit in 2017, expressed what would appear to be an obvious conclusion.

vns bug

"There's been lots of increase in people with zero debt, so we're accepting more rich kids," Dicks said, according to an article in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

In a recent email to the VIN News Service, Dicks suggested that studying the demographics of zero debtors could offer valuable insight. "Are we following their professional paths to better understand if and how the labor force will change as costs continue to rise and price out less wealthy potential vets?" he asked.

According to AVMA President Dr. Douglas Kratt, research is underway to identify demographics and factors associated with veterinarians who graduate with the highest debt levels and those with none, and how the simultaneous increase of students at both ends of the debt spectrum will impact the profession. By email, he said efforts are ongoing to pinpoint the conditions that allow more students to graduate debt-free and "identify tactics that could be replicated more broadly."

Interviews with a smattering of zero debtors suggest that their financial backgrounds and journeys toward funding their veterinary degrees are diverse. Finding students who are willing to talk about it isn't easy. Those without debt often keep it confidential, for fear of alienating classmates. But some don't.

Dr. Donna Harris has led financial literacy courses at Michigan State University for 10 years. In 2018, MSU bulked up its financial literacy curriculum, going from a single three-credit course offered once in the first year to five one-credit courses taken for the five semesters before clinical training. The first class to complete the sequence will graduate in 2022.

Zero debt chart, 2020

Harris has found in her courses that not everyone who hasn't borrowed for school is mum about it: "I've always had a student or two who would like everyone to know they don't have any debt."

Harris encourages them to be thankful to whomever put them in that fortunate position. In some cases, students can thank themselves. "They have saved in their earlier career or have had military service," she said.

No substitute for hard work and a plan

Marine veteran Bryan Moulton, in his fourth year at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine, is among those who anticipate graduating without student debt.

To pay for his veterinary education, the 36-year-old from Colorado Springs tapped military service benefits through the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill, for the $21,000 or so in tuition and living expenses that the program costs per semester.

GI Bill benefits provide up to 36 months of tuition and housing to military veterans who complete at least four years of active duty. (The CSU veterinary program is 30 months over four years.) While the GI Bill often is applied to undergraduate education costs, Moulton used personal savings to pay for the majority of his undergraduate degree at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, and reserved his military benefits for the pricier veterinary program.

Bryan Moulton

Photo courtesy of Bryan Moulton

Veteran marine Bryan Moulton uses benefits from the GI Bill to pay for his veterinary education. He'll be debt-free when he graduates in 2022 from Colorado State University.

Financial acumen didn't come naturally to Moulton. It was forced upon him as a young marine in 2004. "I went on my first deployment with 98 cents in my bank account, and I mostly spent my money on weekend adventures and frivolous equipment," he recalled. "My team leader found out the amount and quite literally threw a book on finance at me."

The book, Robert Kiyosaki's "Rich Dad Poor Dad," spurred Moulton to save, and invest 20% from each paycheck. "I also re-enlisted twice, in combat zones, so I got bonuses, which I used to purchase CDs [certificates of deposit]," he said.

By the time he left the military in 2014, Moulton's CDs had matured, providing enough to pay most of his undergraduate tuition without dipping into his mutual fund investments. "I also worked about 25 hours a week for the last 2½ years of my undergrad," he said. "And I lived with my parents. I paid just over $40,000 out-of-pocket."

Inspired by watching medical dramas on television, Moulton set his sights on medicine after graduation. He chose veterinary medicine rather than human medicine, having volunteered in a veterinary hospital. "They liked my work ethic," he said. "I was helping with animals and in the lab. I researched it, and veterinarians are able to do so much more with their degrees than doctors can, because doctors in human medicine are limited to their area of specialization."

He credits his experience on military reconnaissance missions, small-scale raids and parachute operations for fostering an ability to live frugally and with thoughtful intent, even if a lot of his training doesn't translate to life as a civilian. "That experience," he said, "has given me an advantage."

Asked if he keeps quiet about his debt-free status when around classmates carrying heavy student loan debt, Moulton said that depends on the situation. He shared the story of a fellow student who earned her undergraduate degree from a private university and attended veterinary college as a nonresident, meaning she paid a higher tuition rate. He sighed. "She owes more than $350,000."

To her and others in a similar bind, Moulton said he's willing to discuss financial well-being. It's all about planning and doing the legwork, he said: "Know how much debt you plan to have at the end of vet school. If your plan is limited to 'I'll just pay for it with all of my loans each semester,' you are going to graduate with a high debt load. Figure out how much you'll actually need, meaning, make a budget and stick to that. Look for scholarships, look for work opportunities, look for grants."

Because he's proud of his 12 years of military service and the benefits it affords, Moulton readily shares his story with other veterans. "A lot of people who were in the military don't know that you can save your GI Bill [benefits] for graduate school," he said. "They spend them on their undergrad, which is less expensive. So I try to let people know not to do that."

He doesn't, however, share his debt-free status with potential employers, in case they get the impression that they can hire him at a bargain because he doesn't have loan payments. After graduation, Moulton — whose interests run to surgery, emergency medicine and client education — plans to work in small animal general practice in Northern Colorado.

To aspiring students, he offers this: "In the end, the cost of education is fairly fixed, and as long as schools keep adding administrators to the staff, the cost will continue to rise. You have to be OK with that and have a plan for dealing with debts from school, or you will stress yourself out in school or in practice."

Feeling like an outsider

Sarah Edwards, a fourth-year student at Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, is stressed, but not about student loan debt. The 30-year-old from Louisville, Kentucky, anticipates graduating debt-free next spring with plans to continue on to a small animal internship followed by a three-year residency.

What concerns Edwards is how much time remains to reach her goal. "Best-case scenario, I get out of school when I'm 35," she said.

Cost wasn't a "huge factor," she said, when she applied to nine veterinary programs and was accepted by all of them. "If I liked a school, that was what was important. I was deciding between here and Tufts, which is more expensive," she said. "I was fortunate to have so many choices."

Sarah Edwards

Photo courtesy of Sarah Edwards

Sarah Edwards graduates in 2022 from Washington State University's veterinary college and plans to specialize in internal medicine. Being free of student loan debt puts her "in a good spot financially to be a resident or intern," she said.

Edwards said her parents, who own an aluminum extrusion company, offered to pay for her undergraduate education at Tulane University in New Orleans, but she won a full academic scholarship. She's using money from a trust fund set up by her grandparents to pay for her veterinary education and estimates that she's spent around $115,000 on the program so far.

Edwards does not readily divulge to classmates that she doesn't have school debt. "My dad always told me, 'Never let anyone know how much money you have,' " Edwards said. "He's very private about it. I never grew up talking about money with my parents. I've told very few people."

But debt often is an open topic of conversation among classmates who borrow to pay for their education, she said: "It's definitely more from people who have loans. I know there are other classmates who are graduating without debt, but they don't talk about it."

She recounted the time she overheard classmates speaking in a derogatory way about a fellow debt-free student, behind the student's back. "Whenever those conversations come up, I don't say anything," Edwards said. "... I know how fortunate I am, and I'm so thankful, but I don't want anyone to know about it."

The situation has caused strain with significant others. "I would say I really struggled with the whole money topic," she said. "It's just really hard. At some point, they figure out that my parents pay for everything, and sometimes, I think I'm taken advantage of."

Using good fortune to give back

Prentiss, whose parents pay for her studies at LSU, said she doesn't openly talk with others, not even roommates, about her lack of student debt.

"I don't volunteer that, so not many people know," she said. "I understand that a lot of my classmates are in crippling debt."

When she graduates in spring 2023, Prentiss plans to relocate to Thailand to work with a low-cost veterinary practice as a member of the Christian Veterinary Mission, a faith-based group that supports veterinary missionaries around the world. The move, Prentiss said, would be hard to make if she were saddled with high debt. She says her mother, who emigrated from Thailand to the U.S. in 1995, is open to the idea and wary at the same time.

"Quality of life in Thailand is so very different from here," she said. "Political situations are rocky, and missionaries do not make much money. But the people there really need veterinary care."

Prentiss is grateful for her father's insistence that she go to a relatively affordable program. Eventually, she'd like to open her own low-cost mixed-animal practice in Thailand, which might not be realistic if she were heavily indebted.

"While I couldn't go to my first choice in vet school, after learning just how bad the debt situation is today, I'm really glad that I didn't," she said.

Edie Lau contributed to this report.

Part 1: Still broken, five years after Fix the Debt veterinary summit

Part 2: Purdue shows freezing price of veterinary school is possible

Editor's note: The headline has been changed from the original to reflect that the story is about the prevalence of students who graduate without debt, not tips for avoiding it.