Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Lead photo

Photo by Riis Williams

The Schwarzman Animal Medical Center, located in Manhattan's Upper East Side, is having 15,838 square feet added, bringing the facility total to more than 83,000 square feet.

Every week, Helen Irving receives calls from prospective buyers wanting to know: Is the hospital for sale?

And every time, Irving, president and CEO of Schwarzman Animal Medical Center of New York City, replies, "No, we're not for sale." On the contrary. "We are investing in our future," she says.

The investment, at the moment, looks like this: A construction hoist running up the side of the nine-story building. Scaffolding largely concealing the entrance. Wires hanging from exposed ceilings. Tarps and sheets of plastic everywhere.

The unglamorous surroundings represent growing pains that promise to deliver more spacious, comfortable and modern facilities to an organization well into its second century in operation.

Known in veterinary circles simply as AMC, the institution was founded in 1910 and occupies a 1960s-era building on New York's Upper East Side that it has outgrown. Billing itself as the "largest nonprofit veterinary hospital in the world," AMC tallies some 60,000 patient visits a year and has a workforce numbering 548, including 132 doctors, 139 veterinary technicians and 122 veterinary assistants.

A capital campaign announced in 2019 has raised more than $100 million from 125 donors. One donation is AMC's single largest ever, $25 million, given by New York philanthropists Stephen and Christine Schwarzman. Stephen Schwarzman is founder and head of the private equity company Blackstone Group, and Christine Schwarzman is a lawyer. AMC honored the couple by adding their name to the hospital.

So far, the hospital has completed a new surgical suite, with touchless doors that open with the wave of a hand. When construction is finished, anticipated next year, the hospital also will have a larger emergency room, intensive care unit and special care unit; a new outdoor dog run and park; a new education and conference center; and a renovated first-floor lobby.

The fundraising effort has been so successful that AMC has twice reset its goal — first from $70 million to $100 million, and now to $125 million.

Explaining the repeated revisions, Irving said that as the project progressed, "it became apparent that there were other areas of the hospital that, if we didn't upgrade now, we'd have to soon after. ... It made more business sense, while the walls of the building were open," she said, "to bite the bullet and get a new MRI machine," for example. (A crane lifted the 4.2-ton machine to the eighth floor.)

AMC's ability to attract donations by the millions may not surprise those familiar with its stature. The organization has had a formative influence on the U.S. veterinary profession. AMC, along with another East Coast nonprofit, Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston, pioneered 24-hour emergency care and specialty practice, and both are pillars of veterinary postgraduate education.

AMC's internship program dates back 60 years and its residency program about 50 years, with more than 2,500 alumni.

Specialty veterinary practice today largely follows a for-profit model, departing from its roots at AMC and Angell. Except for public university teaching hospitals and a handful of private nonprofits, emergency and specialty veterinary practices are commercial enterprises, with 75% to 80% owned by a few large corporations, according to an estimate of Brakke Consulting, an animal health firm.

As pet owners increasingly consider their animal companions part of the family, the demand for sophisticated veterinary care grows apace, creating fierce competition for specialists. That puts pressure on all players, AMC included, but the organization will remain a charity, Irving promised.

"My board is adamant and fiercely guarding AMC's nonprofit status," she said. Selling itself to a for-profit business "would not be entertained," she maintained. "We will truly stay independent."

Despite a hot market for veterinary professionals, Irving said, "We're filling our vacancies. ... Our veterinarians like to work here because we know we can do uncompensated care; because we know we can do charitable care, which, in the private sector, does not always happen. We're not measuring [doctors] by how many cases they see. We don't have a production model. That brings a whole level of difference in comfort coming to work."

Another perk AMC offers is housing at below-market prices for interns, residents and, on a temporary basis, new hires. The organization owns a 79-unit condominium within walking distance of the hospital.

Entrance

Photo by Riis Williams

With construction underway, the hospital entrance is somewhat hidden.

While veterinary emergency rooms can be especially hard to staff, owing to the tough hours and a high-stress atmosphere, Dr. Jennifer Prittie, head of AMC's emergency and critical care department, said competition with for-profit practices for staff emergency doctors and criticalists is minimal, and turnover is low. She credits the department's quality of medicine, the strength of its teaching program and staff camaraderie. "Doctors stay because of these reasons, often for years and years, when they could make much more money elsewhere," Prittie said, noting that many interns and residents end up remaining at AMC for most of their careers.

Count her among those who stayed. Prittie joined AMC as an intern in 1997. At the time, there were no critical care-designated veterinary technicians. No overnight intern supervision. Staffers were regularly pulled from other services for ER duty. In 1998, Prittie became the department's first-ever resident. Today, she can call AMC her family — literally. Her spouse, Dr. Chad West, is an AMC veterinary neurologist who also interned there.

Another long-timer is Dr. Ann Hohenhaus, host of AMC's podcast Ask the Vet and the hospital's sometime spokesperson. Hohenhaus arrived at AMC as an intern in 1986, stayed for a residency in oncology, then took a staff position.

Hohenhaus said a key attraction of working at AMC is its deep pool of specialists — 43 — who support and intellectually challenge one another.

"I would not want to be the only oncologist working at a hospital, because I want my patients to have care when I'm not here," she said. "I want a colleague to bounce ideas off: 'What do you think about this?' 'I've never seen this before, have you?' 'What about this drug?' When you practice alone," she said, "you're always right, because you have no one to tell you you're being stupid and are wrong."

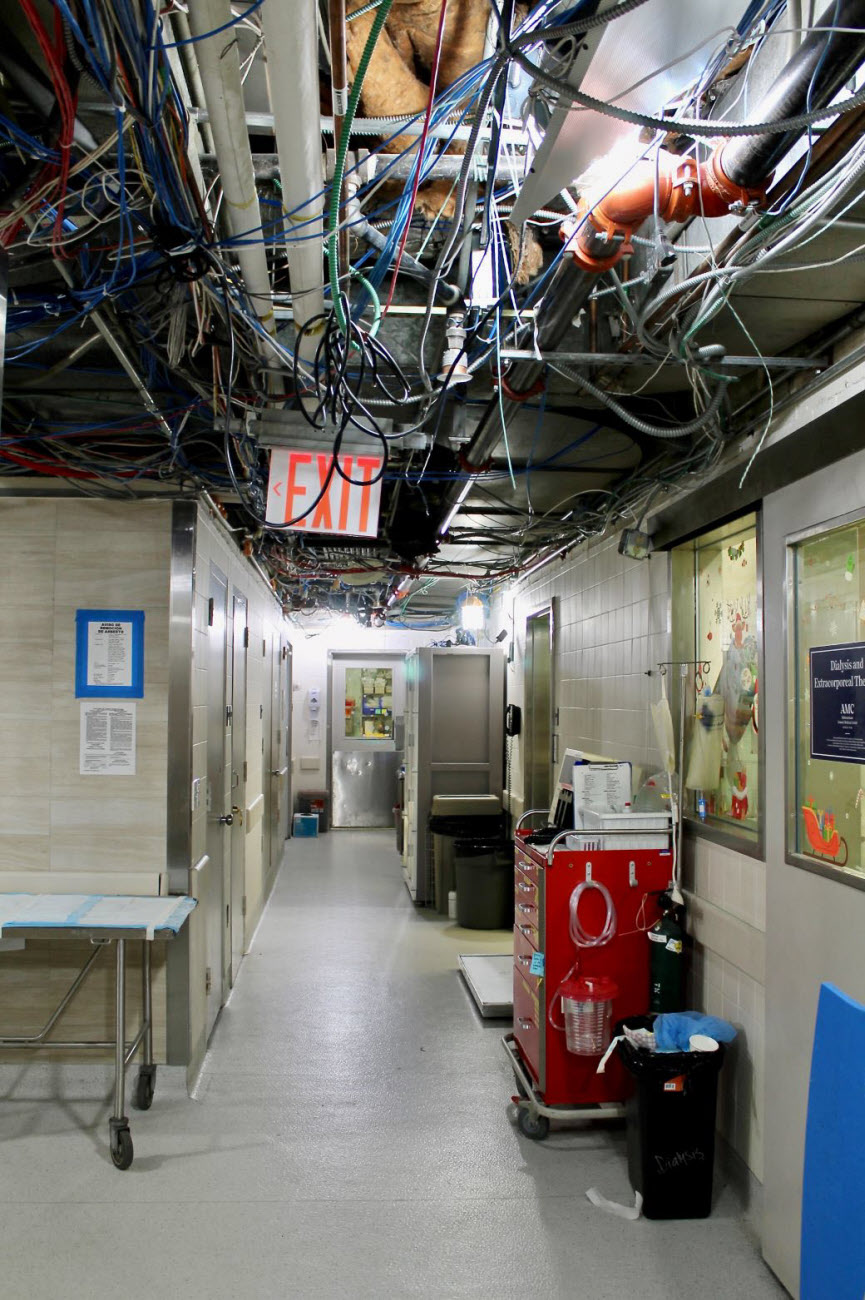

Hanging wires

Photo by Riis Williams

Exposed wires reveal a building in transition. Nevertheless, the hospital continues to operate around the clock.

Asked her thoughts on why specialty veterinary care has evolved into a largely for-profit endeavor, Hohenhaus pointed to set-up costs.

"You can't have a specialty hospital without a CT, an MRI and a lot of staff, and just getting that set up takes a lot of money," she said. "When AMC started, there were no specialities, and AMC was instrumental in starting specialties, so we were able to add a little at a time rather than having to buy the whole bottle of wax at one time."

How it evolved

Dr. Steve Ettinger remembers well the days before specialties were commonplace. A graduate of Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine in 1964, he was part of AMC's very first group of interns. While many of his peers set their sights on Angell in Boston, which established its internship program years earlier, Ettinger wanted to be in New York City near family. AMC was looking at the time for six interns, he recalled. "Four of us applied. We were all accepted, and the rest is history."

The interns were a plucky group. Ettinger, the younger brother of a physician who specialized in cardiology, had an interest in and knowledge of hearts and began working on cardiac cases. Two other interns had an aptitude for surgery. Ettinger said he was invited by the head of the hospital to participate in a comparative medicine program in cardiology that was being taught jointly at the Veterans Administration hospital in the Bronx and at AMC.

About six months in, Ettinger and the surgically inclined interns proposed starting a round-the-clock surgery emergency clinic. "There's nobody seeing emergencies in the entire city of New York, all five boroughs," they pointed out. The hospital agreed and assigned the young veterinarians to staff it.

"So the three of us did overnight shifts, which were all night long, and we worked the day before and the day after. And we got paid, I think it was, like, 50 bucks a night," Ettinger said, sounding gleeful at the memory. "We had a wonderful time together."

Angell, too, had recent upgrade

Following his internship, Ettinger landed a National Institutes of Health two-year fellowship in cardiology, enabling him to continue his studies at AMC and Bronx VA. He also began organizing courses and lectures on various aspects of veterinary medicine at AMC and inviting colleagues from across the city to attend, an act that he said thawed what had been an icy relationship between the nonprofit hospital and its for-profit competitors.

Ettinger ultimately spent seven years at AMC, a period during which a variety of veterinary specialties began taking shape. He moved on to California, where "with four other veterinarians, we opened the first veterinary group specialty practice in the country," he recounted. Located in Berkeley, the practice offered services in internal medicine, surgery, radiology, ophthalmology and dermatology. In 1973, Ettinger helped found the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, which currently represents six specialties.

Altogether, 46 distinct specialties are recognized in veterinary medicine to date. AMC's board-certified doctors represent most, but not all, of those disciplines.

Past and coming changes

The organization that established AMC in the early 20th century was the New York Women's League for Animals, which was initially motivated by concern for the welfare of horses in an era when horses were an essential mode of transportation.

Over the years, as society changed, so did AMC's patient mix. These days, aside from an occasional foal or zoo inhabitants such as penguins, AMC tends to household pets. It still offers primary care, but its emphasis is specialty and emergency medicine.

One reason space has become tight is that medicine keeps having more to offer, Hohenhaus said. "Every time there's a new advancement in medicine, AMC adds. I don't think we ever subtract," she said. "It used to be that once you did X-rays and a blood count and looked at the liver and kidneys and urine, you were kind of out of tests. Now there's an infinite number of tests."

When construction is completed, the facility will top 83,000 square feet, an increase of 24%.

The growth will directly affect patient care. With more space, for example, the emergency room will have 16 cages instead of five, according to Prittie. For an ER that doesn't turn away any patient brought to the premises needing life-saving care, the existing limited capacity at times requires improvisation. During rushes, staff have at times resorted to fashioning makeshift cages from cardboard boxes — a practice Prittie hopes will not be necessary post-renovation.

The ICU, now windowless, will get windows. The number of regular cages will rise from 14 to 24 and oxygen cages from four to 12. There will be a new isolation ward for patients that need to be quarantined.

ICU

Photo by Riis Williams

Intensive care unit staff, including (from left) patient care assistant Melissa Silva, intern Dr. Kaity Smith, and team leader and veterinary technician Shannon Brathwaite, work in a tight environment for now. Post renovation, the space will have natural light and room for more cages and other amenities.

Irving, the CEO, joined the hospital a little over a year ago after being lured out of retirement. A registered nurse with an MBA, Irving spent a large part of her career managing health care institutions. As AMC's capital project winds toward completion, she's begun thinking of expansions of a different sort.

Offering mid-career education is one idea. "We have such great doctors. These doctors could be teaching other doctors that have been in [the profession] for some time but want to hone their skills," Irving said. "... This [would be] on-site, come-train-with-us type programs."

Another possibility is developing hospitals beyond New York City. "One of the benefits of AMC that the doctors all like is that we're in the same place — so there are pluses and minuses" to being in multiple locations, Irving said, "but if we're talking about access to care, that's a different conversation."

From her own home in upstate New York, the nearest specialty hospitals are more than 100 miles away, Irving said. "We are thinking about 'What should AMC look like five years from now? Should we be a robust physical presence throughout New York so we can improve access to services?' "

While such big-picture questions are contemplated by AMC leadership, the New York City veterinary team relishes a sense of ownership in what the hospital is building, physically and figuratively.

For Prittie, the long-awaited renovation feels like an embodiment of her life's work. It's overwhelmingly gratifying, she said, to witness the transformation of a place that not only defines her career but is the foundation of her closest relationships.

"I am what we call an AMC lifer," she said. "I will retire from here and so will many others who started here so early in their careers. I don't know who I'll eventually be passing the torch to, but the idea of having this huge beautiful ECC [emergency and critical care] department that I was instrumental in creating and growing — and that will be here for years to come — is a pretty neat legacy."

This article was changed on April 2, 2024, to correct the number of veterinarians employed by MSPCA-Angell. The number is 118, not 33, the figure that was initially provided by Angell.