At Christmastime, Jessica Mantoani opened her home in San Carlos, California, to a beautiful golden retriever from South Korea in need of a foster family.

At Christmastime, Jessica Mantoani opened her home in San Carlos, California, to a beautiful golden retriever from South Korea in need of a foster family.

Mantoani recalls feeling proud that her local rescue organization, Doggie Protective Services, aimed to save animals from Korea’s dog-meat trade by bringing them to the United States. Having volunteered for years with the nonprofit, Mantoani's main concern was whether the foster dog would blend well with the three beloved canines she had at home.

That wasn't a problem. "The dog was friendly, had a lot of energy," Mantoani said. But another, more serious, issue arose.

"[W]e noticed about two days after he arrived that he was coughing and would spit up white, goopy stuff onto the floor," she recounted. Mantoani guessed it was a mild case of kennel cough. "It didn’t seem to bother him; he had no other real symptoms," she said.

Mantoani contacted the rescue group, which took the dog to be treated for an upper respiratory infection and returned him to her home. Then Mantoani's younger dog, Sheldon, stopped eating, started coughing and became lethargic. Her two elderly Jack Russell terriers, Bailey and Tildon, also became ill — gravely so.

On New Year’s Day, 11-year-old Tildon began vomiting and having seizures. After a harrowing trip to the SAGE Centers for Veterinary Specialty & Emergency Care in Redwood City, the dog perished.

Mantoani later learned that the golden carried H3N2, a virulent, potentially deadly strain of canine influenza that public-health experts say is being spread to the U.S. from infected dogs imported from foreign countries.

Sheldon eventually beat the virus. Bailey almost didn't. "My daughter was sleeping next to the dog, praying over her and playing 'Hallelujah’ on repeat," Mantoani recalled. "... The next morning, Bailey was sitting up. This dog has nine lives. She still has a lingering cough, but the fact that she's living is a miracle."

Doggie Protective Services eventually reimbursed Mantoani the $3,500 she spent on veterinary care for her three dogs. The organization still partners with a Korean exporter of animals. "It is our strong belief that because we have the resources and the ability to save highly adoptable dogs from certain death, that we should do so," the website reads. "It doesn't matter if the dogs in need are in the Bay Area, LA, or as far away as Korea. Our philosophy is simple: If there is a need, and we can and want to assist, then we will."

The VIN News Service was unable to reach officials with the nonprofit for comment. As for Mantoani, she says she'll never again house an imported animal.

"I never thought about canine influenza," she said. "They told me the dogs from Korea were quarantined for 30 days, so I wasn't worried. I had never known a dog to have the virus, and now it seems to be everywhere."

Are U.S. importation rules lax?

Doggie Protective Services is one of many well-intentioned welfare groups relocating dogs from Asia to the U.S. and other western countries. In Canada, H3N2 was introduced earlier this year after Detroit-based MotorCity Greyhound Rescue unwittingly imported two infected dogs from South Korea to the United States. The dogs had foster homes on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border.

Officials with the nonprofit told a news station in Ontario the dogs had been quarantined for three months in South Korea before making the overseas trip, and they had "no way of knowing" the dogs were ill.

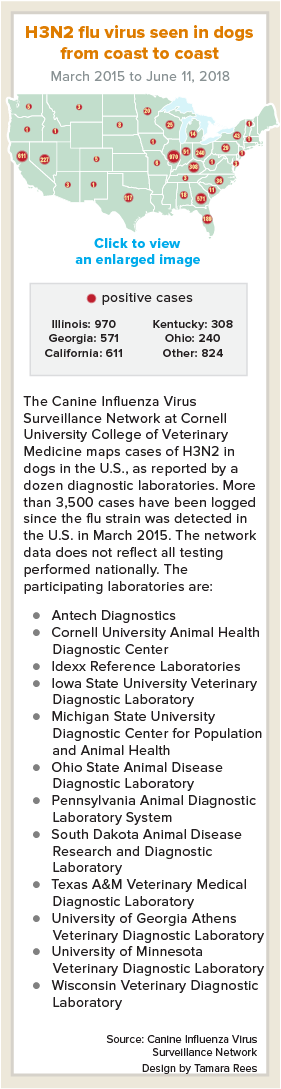

In the U.S., thousands of dogs have tested positive for the disease since it first appeared in the country in 2015, in Chicago. Researchers traced the Chicago outbreak to canine influenza virus circulating among dogs in South Korea.

Outbreaks appear to peter out after a couple of months, but a single new case can send the virus rapidly spreading. Mantoani's sick dogs jumpstarted a two-month deluge of cases seen by veterinarians in and around the San Francisco Bay Area. Since then, H3N2 has emerged in pockets of Minnesota, Nevada and elsewhere. Last week, more than three dozen H3N2-positive dogs were identified in and around New York City.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now considers H3N2 to be endemic in the U.S.

Edward Dubovi, a professor of virology at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, has tracked canine influenza virus (CIV) since 2004, when Cornell’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center helped isolate the first flu subtype — H3N8 — found to sicken dogs.

Today, at least two subtypes are known to infect dogs: H3N8 and H3N2. The first is believed to have jumped from horses to racing greyhounds and moved on to the general canine population. Illness from H3N8 appears to have all but burned out in the U.S.

In its place is the more virulent and deadly H3N2. Researchers identified the avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza virus five years ago circulating in farmed dogs in Guangdong, China.

Canine-influenza fears led authorities in Australia last month to temporarily suspend dog importations from Singapore after H3N2 was detected at the border, according to media reports. New Zealand also beefed up restrictions following a recent outbreak at a quarantine facility.

To date, the United States has not followed suit.

Multiple U.S. government agencies oversee the importation of animals, but their focus is public health and zoonotic diseases — diseases that can pass from animals to humans — as well as food-producing animals. "CDC does not track the number of people bringing pets into the United States. CDC intervenes only in cases of potential public health threats related to the importation of pets (primarily dogs)," LaKia Bryant, an agency spokesperson, explained by email.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, which regulates the importation of commercial dogs into the country, doesn’t address canine influenza, either. USDA requires imported dogs to be healthy and vaccinated for rabies, distemper, hepatitis, leptospirosis, parvovirus, and parainfluenza virus. In most cases, dogs must be at least 6 months old and have health and rabies vaccination certificates issued in English by a veterinarian with a license to practice in the country of export. An import permit from APHIS also is needed.

Social activism — the desire to save dogs — is trumping science, Dubovi contends. "No one wants to be the one to say, 'Let’s stop importing these dogs from Korea because they’re bringing diseases,' " he said. "They don’t want to admit it."

Dubovi is among a growing number of scientists calling for more restrictive entrance rules. The importation of dogs, he said, is "totally uncontrolled" and costing U.S. pet owners millions of dollars in veterinary medical expenses.

"If these were pigs, USDA would be going berserk about this," he said. "Every U.S. port that can bring dogs in from overseas is doing it. Once they’re here, there’s no required quarantines. And you can buy fake rabies certificates.

Dr. Camille Fischer of Redwood City, California, and her daughter, Charlotte (right)

Photo courtesy of Dr. Camille Fischer

Veterinarians warn that dogs imported from overseas can bring with them dangerous diseases. Dr. Camille Fischer of Redwood City, California, and her daughter, Charlotte (right), spent a recent Saturday at People's Park in Berkeley to educate the public about H3N2 canine influenza virus and other issues.

"The costs of this problem are immeasurable," he said.

USDA APHIS did not respond to VIN News requests to address those concerns.

Another wrinkle

Last week, researchers raised another argument for strengthening canine-importation requirements.

In a study published June 5 in Mbio, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology, scientists report having demonstrated that the H1N1 flu virus — a potentially deadly subtype of influenza that’s responsible for sickening humans — can jump from pigs to canines.

Should H1N1 mix in dogs already carrying H3N2 or H3N8, the reassortment could result in a novel zoonotic version of the flu, the study says. That means dogs might one day be the source of a global flu pandemic, the researchers warn.

"CIVs from this study were collected primarily from pet dogs presenting with respiratory symptoms at veterinary clinics, but dogs in Guangxi are also raised for meat, and street dogs roam freely, creating a more complex ecosystem for CIV transmission," the study states. "Further surveillance is greatly needed to understand the full genetic diversity of CIV in southern China, the nature of viral emergence and persistence in the region’s diverse canine populations, and the zoonotic risk as the viruses continue to evolve."

The study’s lead investigator is Adolfo García-Sastre, director of the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute and principal investigator with the Center for Research on Influenza Pathogenesis, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. In a press release, he said that the majority of pandemics are associated with pigs as an intermediate host between avian viruses and humans.

Identifying influenza viruses jumping from pigs to dogs had not been documented until now.

"In our study, what we have found is another set of viruses that come from swine that are originally avian in origin, and now they are jumping into dogs and have been reassorted with other viruses in dogs," he explained. "We now have H1N1, H3N2, and H3N8 in dogs. They are starting to interact with each other. This is very reminiscent of what happened in swine 10 years before the H1N1 pandemic."

Dr. Camille Fischer, a veterinarian in Redwood City, California, believes the relatively benign nature of the first known dog-flu subtype — H3N8 — has led the public to become nonchalant about canine influenza in general. "H3N8 is our model of a disease that's smoldered in our communities," Fischer said. "[Because] it's a lot less dangerous to dogs than H3N2 is ... it's led people to be complacent [about] H3N2."

She added: "When you do an internet search, there's almost nothing to explain the differences between these two viruses, and they're dramatic. H3N2 is much more deadly."

Fischer called the inadvertent transport of deadly pathogens through animal-rescue operations an "unnecessary tragedy, where good intentions have led to serious consequences."

On a mission to educate the public about the dangers of importing improperly screened animals, Fischer maintains that U.S. standards should include more quarantine, testing, vaccination and parasite treatment of all animals entering the country. "I advocate for improved regulatory oversight of pet animal importation and public education to promote reasonable safety precautions, particularly related to pet rescue," she said.

She considers the need for reform to be urgent.

"I'm trying to help the public to see situations that have been alarming academic professionals for many years," Fischer said. "These [disease-causing] organisms have devastating effects when they are introduced to new geographic locations."

Seeing H3N2 close up

During her bout with the flu, Mantoani's Jack Russell terrier Bailey was seen by Dr. Justin Daughtry, just two years out of veterinary medical school and then working at VCA Holly Street Animal Hospital in San Carlos.

Daughtry observed that the dog was severely lethargic, with nasal discharge. "She was barely ambulatory and had a fever higher than 104 degrees," he recalled. "The first thought in my mind was, 'This is definitely not kennel cough.' I initially thought I was looking at distemper."

A test for distemper came back negative. Daughtry then consulted his practice’s medical director and internal medicine specialist, Dr. James Bower. Bower suggested the culprit could be flu.

"I was like, 'Yeah, I guess it could be,' " Daughtry recounted. He'd considered flu a long shot at first. "The funny thing is, going through school, people would say [dog flu is] in isolated areas. Unless you’re in Florida around greyhounds, or in Chicago, which has had a limited outbreak, you don’t have to worry about it," he said. "That was my bias going into practice here."

He added: "I had no idea that one strain was more virulent than the other dog-flu strain. I knew there were certain bird flus that are deadly in poultry. I knew that there were outbreaks that cross over to humans. I never really extrapolated that there were different flavors of dog flu."

From his experience, Daughtry believes veterinarians who face H3N2 for the first time are in for an abrupt education. For weeks after seeing Bailey, his schedule was full of dogs sick with the flu. The veterinarian changed his clothes at work and washed thoroughly before leaving each day. Even so, he carried the virus home. Daughtry's own dog became ill.

He was fortunate. His pet made a full recovery.