Image 1 320

Screenshot of AVMA Convention session

Stress levels, high student debt and suicide are top concerns for veterinarians, according to results of the Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Study 2020. "You’ll see that suicide of veterinarians is even more concerning now than it was two years ago," said John Volk of Brakke Consulting (left).

Click here for a larger view

Many U.S. practitioners would not recommend their profession to friends and family members, citing stress levels, burdensome student debt and suicide. Still, they rate their work as highly satisfying, taking pride in it and the positive impact it has on people's lives, according to a survey conducted late last fall of 2,871 practitioners from across the country.

Those findings and others are part of a Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Study 2020, which compares mental health and well-being in the profession with that of physicians and the general U.S. population. The research was summarized last month during a session of the AVMA Convention, held virtually due to the pandemic.

Among topics examined in the wellness study are job satisfaction; compensation; burnout; substance-use disorder; cyberbullying; and suicide ideation among veterinarians. The findings build on mental health and wellness data gleaned from a similar Merck-funded wellness study conducted in 2017.

Brakke Consulting, an animal health management consulting firm, administered the survey last fall in collaboration with the American Veterinary Medical Association. The study, named for sponsor Merck Animal Health, a pharmaceutical company, was conducted via an online survey distributed between Sept. 30 and Oct. 23, 2019, before the emergence of COVID-19.

Like many professions, veterinary medicine has not looked the same since March, when the spread of novel coronavirus was recognized across the United States. Asked whether the study's findings hold up mid-pandemic, Brakke Senior Consultant John Volk surmised that the state of mental health and well-being since COVID is likely bleaker.

"Veterinary medicine is a stress profession, as is human medicine," he said by email. "The pandemic has only made it worse. These stresses are probably negatively impacting well-being. Plus, COVID has made it more challenging to socialize, and socializing with family and friends is important for well-being and mental health."

Attitudes over time

Still, results from the latest wellness study are valuable, Volk said, marking trends gleaned from survey responses collected in 2017 and again, in 2019. Overall, not much has changed in terms of how veterinarians view their profession, he said during the online presentation to AVMA Convention attendees.

Attitudes from veterinarians in 2017 and 2019 about endorsing the profession to friends and family were "almost identical," Volk said. "There was hardly any difference at all, much less any statistically significant difference," he continued.

The 2017 study found that 33% of the veterinarians polled would recommend a career in veterinary medicine, and 41% would not.

Volk said that although the 2019 data differed, the results offered a similar picture: 48% of veterinarians polled said they'd recommend a career in veterinary medicine, and 52% said they would not. What changed, Volk explained, is that the 2019 survey forced "yes" or "no" answers while respondents in 2017 were permitted to answer that they did not know or have an opinion about whether to recommend the profession.

Volk pointed to similar research on physicians, which shows marginally more positive but similar results. According to a 2018 survey of nearly 9,000 doctors, 51% of respondents said they'd recommend a career in medicine; 49% would not.

The only open question in the 2019 wellness study, Volk said, asked respondents why they might not recommend a career in veterinary medicine. Among respondents' chief concerns: high student loan debt (91%), high stress levels (92%) and suicide in the profession (89%).

New veterinarians earn about $85,000 a year and, on average, those who graduate with debt owe approximately $185,000 in student loans, according to AVMA economists. Many enter the profession with loans double that, while roughly 20% graduate debt free, the AVMA reports. "Finances play the biggest role here; clearly, those are the things that worry veterinarians and make them less likely to recommend the profession to other people," Volk said.

Despite the downsides, veterinarians rated job satisfaction highly, agreeing with the statements: "I'm invested in my work and take pride in doing a good job" and "My work makes a positive contribution to people's lives." Many respondents said they considered the veterinary profession to be more of a calling than a career, and cited "very altruistic types of factors" that contributed to their job satisfaction, Volk said.

Suicide ideation

Image 2 320

Screenshot of AVMA Convention session

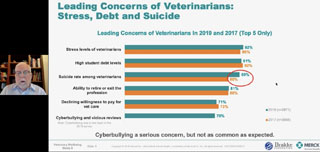

The Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Study 2020 found that veterinarians think about suicide more often than other employed adults in the U.S. However, the study does not provide insight into suicide rates, said John Volk (left) of Brakke Consulting. "We’re taking a survey among living individuals so we don't have any data on those who took their own lives," he said.

Click here for a larger view

While the study found rates of binge drinking and drug use to be low among veterinarians, suicide ideation is widely known to be more prevalent among practitioners relative to the U.S. general population and compared with other occupations. A study last year by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, found that female veterinarians were 3.5 times as likely and male veterinarians were 2.1 times as likely to die by suicide compared with the U.S. population as a whole during the period from 1979 through 2015.

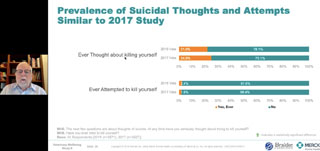

Both 2017 and 2019 wellness studies measured suicide ideation, planning and attempts among veterinarians, and came away with similar findings. Among them: Veterinarians were twice as likely as employed adults in the U.S. general population to think about killing themselves. In terms of attempts, veterinarians were three times as likely to have attempted suicide than those in the U.S. population, with younger, female veterinarians most vulnerable to thoughts of taking their own lives.

The "single highest predictor" of suicide ideation and planning is serious psychological distress, a characteristic most typical of younger, female veterinarians who are introverted and/or highly anxious and depressed, carry a lot of student debt and work long hours, Volk said. Male veterinarians, however, are more likely to attempt suicide.

"We've all heard many, many stories about unfortunate incidents of people taking their own lives," he said, and veterinarians are taking notice. "… Suicide is even more concerning [to veterinarians] than it was two years ago."

Mental health, burnout and well-being

Veterinarians might experience serious psychological distress, but they're also more accepting of it than they were in 2017, Volk said.

Although the mental health of respondents as a whole was statistically similar to findings in the earlier study, reports of serious psychological distress were more prevalent among female veterinarians in 2019 (8.1%) than in the 2017 (6.3%).

In the 2017 study, respondents were asked whether they experienced burnout, and many reported such feelings. For the 2019 follow-up, Brakke approached the question more scientifically so that findings could be compared with those of other populations. The researchers settled on using the Physician Well-being Index, developed at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota to identify physicians in distress and compare their attitudes with those of employed non-physician Americans.

Questions to assess burnout required "yes" and "no" answers. The results:

- In terms of satisfaction in work-life balance, veterinarians and physicians scored almost identically: 39% of veterinarians and 40% of physicians reported feeling satisfied with work-life balance, compared with 61% of the general U.S. population.

- Veterinarians experienced higher rates of burnout than did physicians and other employed adults in the U.S. general population. Hours worked did not appear to play a role because veterinarians, on average, work substantially fewer hours per week than physicians.

- Scores for veterinarians (7.5%) and physicians (7.2%) appear to be almost identical with regard to experiencing suicide ideation during the past 12 months.

Volk said he found no significant difference in responses from 2017 and 2019 to questions about well-being, defined as a subjective measure of happiness. In each study, researchers used an index by which respondents were classified as "flourishing," "getting by," or "suffering." Overall, 9.4% of veterinarians in 2019 were classified as suffering; 34.6% scored getting by; and 56% were flourishing. Similarly, 58.3% of respondents in the 2017 wellness study were described by researchers as flourishing.

Predictors of high well-being included enjoyment of work, having good work-life balance, spending time with family and friends and pay satisfaction. Low well-being tended to be associated with high student debt, younger age veterinarians and those with personality traits such as neuroticism (tendency toward anxiety and depression) and introversion, both of which are prominent in the profession.

"We tested for the big five personality traits, widely used in psychology," Volk said. "Veterinarians scored above average in introversion and neuroticism, which are most closely associated with negative well-being and mental health."

Well-being was similar across all practice types, he added, except for food animal veterinarians, who on average had higher levels of well-being.

Study outliers: food animal veterinarians

Throughout the study, food animal veterinarians appeared to be an exception in almost every category, reportedly happier with less instances of burnout than their companion animal counterparts.

"Serious psychological distress was almost non-existent among food animal veterinarians, both male and female," Volk said.

A number of things may contribute to their well-being and mental health scores, Volk said, including:

- More food animal veterinarians are men, who tend to report higher rates of happiness than female veterinarians.

- A higher concentration of baby boomers comprise food animal veterinary populations. Older veterinarians have higher well-being and less serious psychological distress than younger veterinarians.

- Food animal veterinarians report highest level of satisfaction with the amount of leisure time.

- Food animal veterinarians are more likely to be married, and companionship can aid happiness.

- Food animal veterinarians are more likely to be satisfied with the number of hours worked.

- Food animal veterinarians have lower student debt.

Notably, food animal veterinarians work primarily in an economic environment, whereas companion animal veterinarians work more in an emotional environment, Volk said.

"Food animal veterinarians are rarely standing across an exam table with an upset client wondering whether a procedure should be done or not," he said. "They also tend to spend a lot more time outdoors and work in small communities where they're highly regarded and recognized."

Most haven't experienced cyberbullying

While 70% of survey respondents said they considered cyberbullying and negative online reviews to be critically important issues for the profession, the prevalence of cyberbullying was not as common as researchers anticipated. "When we looked at incidents of cyberbullying, it really wasn't that high," Volk said.

Seventy-five percent of the veterinarians polled said they had never been a victim of cyberbullying; 12% said they dealt with cyberbullying at some point during their careers; and 12% said they had during the past 12 months. Those who spent less time on social media reported fewer negative online encounters.