Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

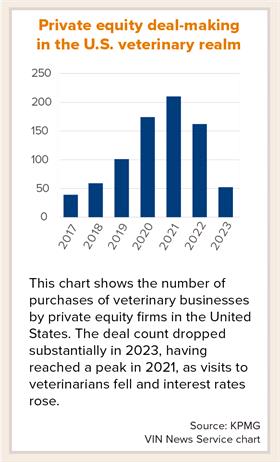

Chart_purchases made by private equity firms

Dr. Trae Cutchin has just done something he would not have anticipated doing a few years back when the so-called pandemic pet boom was stretching veterinary teams to the limit.

He has stopped asking a relief veterinarian to come in one day each week, meaning he is now flying 100% solo at his companion animal practice on the outskirts of Atlanta. He also has laid off one of his support staff.

"We have been seeing a fairly marked slowdown in business right now post-Christmas," Cutchin posted last month to the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service.

"This is often a little slower time of year anyway, but it seems to be more than usual this year," he continued. "So it made me wonder if this is something others are seeing?"

Cutchin's question may resonate with many colleagues around the globe, as strict social distancing measures introduced in 2020 to combat Covid-19 fade from memory.

People once locked down with their pets are now free to go out, making them less apt to lavish their animal companions with attention and fret over every slight sign of illness. Rising inflation, meanwhile, has pushed up living costs, sapping households of disposable income to spend on everything from dog beds and cat scratchers to routine pet health exams and dental work.

The resultant moderation in demand also is being watched closely in finance circles — especially since higher interest rates have increased borrowing costs, making it more expensive for would-be buyers, including private equity firms and other investors, to acquire veterinary practices.

The slump in dealmaking has been significant. Having reached a peak of 210 deals in 2021, the number of purchases made by private equity firms of veterinary businesses in the United States moderated to 162 in 2022 before dropping to 52 in 2023, according to data provided to the VIN News Service by consulting firm KPMG.

Still, expectations that the world's central banks may soon start cutting interest rates is fueling predictions that another round of practice consolidation could be on the horizon. And, even as some veterinarians see visits decline, many others say business remains buoyant — or at least buoyant enough to keep veterinarians in short supply.

‘Weaker tailwinds but no headwinds'

Cutchin found good company among practitioners who responded on the VIN message board to his question about demand. Around a dozen said they'd also noticed a slowdown during January and/or February, with levels of concern ranging from being "a little freaked out," to a calmer regard of the situation as a return to a pre-pandemic "normal."

"This January has been the first post-holiday slowdown that we've had since the beginning of the pandemic," said Dr. Margaret Hammond in Seattle. "We've still got a pretty full schedule, but the schedule is filling up with day-of appointments rather than us sending them to the local urgent care."

Not everyone spoke of a downturn. One practitioner said they were still "swamped." Others indicated business is mixed.

"One day we're all Google-searching bankruptcy lawyers and the next we're all wondering what island we're going to buy," Dr. Glenn Adcock in Spartanburg, South Carolina, posted to the discussion. "I'm not wishing bad business on anyone, but it is nice to know we aren't alone."

Some practitioners even expressed relief that things had quieted. "The slowdown was actually OK for me," Dr. Ebalinna Vaughn in Virginia said later in an interview. "I was able to catch up on a lot of paperwork, and on training a new employee." (Business, she said, has since picked up again.)

Although definitive figures are hard to come by, practice management data collected by Idexx, one of the world's biggest veterinary diagnostic companies, indicates that falling visits are an industrywide phenomenon. At U.S. companion animal practices, visit numbers fell 1.2% in the fourth quarter of 2023 compared with the same period in 2022, according to the company. Year-over-year falls have been recorded by Idexx consistently since the start of 2022, before which there was a pandemic-related surge.

Practice revenue, however, has continued to rise despite declines in visits, the Idexx data shows, likely because of higher prices on veterinary products and services.

Veterinarians are "getting good markups on their drugs, parasiticides and so forth," John Volk, a senior consultant at Chicago-based Brakke Consulting, said.

Consequently, Volk maintains, veterinary businesses remain in a reasonably strong position, even if they're not getting as many visitors as they were in 2021 and 2022.

"We have less tailwind now, but in my estimation, we haven't hit any headwinds yet."

Private equity goes quiet

Even though business has been far from abysmal, the fall in visit volumes, combined with surging interest rates, has made corporate consolidators much pickier with acquisitions.

These days, consolidators — many backed by private equity firms — are offering to buy smaller practices for six to eight times the value of their annual earnings, observes Dr. John Tait, a veterinarian in Guelph, Ontario, who offers consulting services including practice evaluations. Larger practices with earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) of more than $500K to $750K, he said, still can attract higher multiples, but nowhere near multiples in the high teens or low 20s that were being paid in 2021. EBITDA is a commonly used measure of business profitability.

Moreover, offers increasingly are coming with "earn-out" provisions or "retention targets," Tait said, meaning the seller gets a portion of the sale price only if the practice hits earnings targets or retains practitioners for a certain time period.

Volk said a "feeding frenzy" in the fall of 2021 saw what Brakke estimates were some 1,000 to 1,200 practices being snapped up by consolidators that year. By comparison, Volk said, "We estimate that somewhere between 300 and 500 practices were acquired in 2022 and probably fewer than that in 2023."

Though fewer in number, those acquisitions have nevertheless given corporate consolidators a bigger slice of the veterinary pie. In companion animal medicine, Brakke estimates they now own about 30% of general practices and about 75% to 80% of specialty practices in the U.S., together accounting for at least 50% of industrywide revenue (given corporates tend to own larger clinics.)

Ominously, some consolidators could be struggling to meet debt repayments, should they have overpaid for assets when the market was going gangbusters. A quick online scan of local newspaper reports shows that dozens of practices have closed in recent years, though various reasons are given for their demise, including being short veterinarians.

"I don't think some practices were ever worth what people were paying because there was a lot of private capital around," said Tait, explaining that consolidators kept paying high sums for practices expecting a rival would buy it from them later for even more. "Eventually, like a Ponzi scheme, that concept has to stall because future investors can't keep paying higher and higher multiples."

Still, Tait isn't sure that many consolidators are on the brink of closing hospitals en masse. "I think a lot of them are being pushed to the limit, but ultimately what they did to avoid risk was just stop buying."

Cathy Bedrick, a partner at KPMG who works closely with private equity clients, confirmed that some are under strain.

"There's certainly a handful that we know are struggling, but when you look at what's driving the struggle, it's not operational, it's all around financing," she said. "So it's not the fundamental economics of the clinics themselves that's the problem; it's that they put too much debt on them."

Volk has even heard of consolidators selling practices back to veterinarians at lower prices. Still, he noted that many of the more established consolidators have been acquiring practices for decades, many at much more modest prices, lowering their overall risk exposure.

Pricing, pay under the microscope

The lull in consolidation activity has at least given consolidators plenty of time to bolster margins at the practices they already own. Part of that has involved scrutinizing the prices they're charging for veterinary care.

"Now that we've seen some decline in visit volumes, questions are being asked about whether pricing has gotten ahead of the market in certain places," KPMG's Bedrick said.

Prices need not be trimmed (or hiked) bluntly across the board. A more sophisticated approach, she said, could entail tweaking prices in certain geographic locations, or for certain products and services.

Staffing also is in focus amid what Bedrick still sees as a tight labor market. To address that issue, private equity firms might start looking at whether linking a substantial portion of veterinarians' pay to production — a common remuneration method in the profession — is always the right approach.

"It's a very interesting market because you'd think that when production goes up, say 30%, and veterinarians are receiving 30% higher compensation as a result, they'd be happy," she said. "But we actually have a lot of veterinarians who've said ‘I'm perfectly content with what I'm making. I can work 30% less' — and that's putting even more strain on the labor market."

Tait sees few signs the labor market is loosening much, despite the lower visit volumes. "Declining demand tends to move us toward a balance point eventually," he said. "But the labor market's so tight for professionals and non-professional staff right now that I don't think we're going to get there for a while."

Business leaders are telling Volk that labor-market pressure is easing. "But there are an awful lot of job openings out there for veterinarians and for non-veterinarians," he said. "While it's eased slightly from its peak, it's still strong."

What's ahead the rest of this year and beyond?

As for the possibility that visit numbers will rise again, Volk, for one, is bullish. He notes that discretionary income levels in the U.S. are strong in a historic context amid low levels of unemployment.

KPMG, for its part, predicts the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates three times in 2024. Over the longer term, the firm is upbeat, positing that pets increasingly are being valued as family members and, it argues, will get more sophisticated specialist care in old age as their lifespans improve.

"When we look at our clients and the aggregators we talk to, their expectation is similar: that private equity money will re-enter during the back half of 2024," Bedrick said. "We see a lot of people who are getting ready for sale processes, and waiting for that first tick down in interest rates to come off the sidelines."

How much consolidators might pay is unclear, though Bedrick said whoever comes out first with a big acquisition could set the valuation benchmark. "We have some clients who are very eager to do $1 billion-plus investments," she said, indicating that some big takeover bids could be in prospect.

Tait is more cautious, noting that with the labor market still tight, practices remain under pressure from high staff costs. "There's still some uncertainty out there," he said. "We haven't seen, necessarily, a cresting or a decline in interest rates yet."

If and when consolidators do start buying again, Tait agrees large deals could occur, as private equity firms look to fatten margins via economies of scale. He also suspects they'll start looking closely at equine and large animal practices, now that much of the low-hanging fruit in the companion animal realm has been picked.

As for those consolidators that are too big to be acquired (not least due to potential antitrust scrutiny), their backers could launch an initial public offering (IPO), which involves selling shares in a company to investors on a stock market.

JAB, the German investment firm that owns National Veterinary Associates, last year split the business into two divisions — one for general practices and one for specialty hospitals — that it intends to list separately. IPOs for each are planned in "two to three years," JAB said one year ago. Others widely speculated to be considering IPOs include IVC Evidensia and Thrive Pet Healthcare.

Whatever the future brings for big business, Cutchin hopes the lull in demand at his solo practice near Atlanta ends soon.

Summing up his situation, he said: "We aren't in dire straits, not even close. But it is less than desirable."