Sales of antimicrobial drugs for use in animals are falling on both sides of the Atlantic, in a sign that government, animal-health industry and veterinary community actions to combat drug resistance are gaining traction.

Reports from the United Kingdom, the European Union and the United States indicate that overall use of antimicrobial drugs in animals used for food is in a multi-year decline.

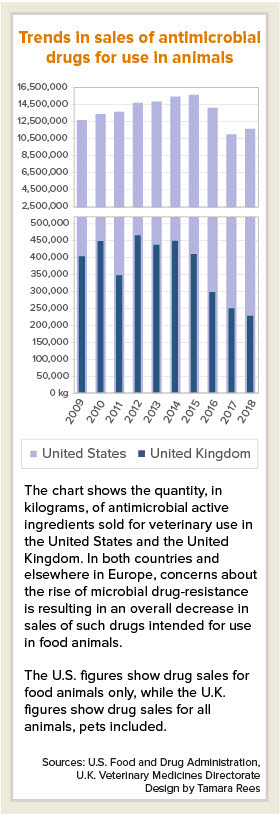

One caveat: The latest figures from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, released last week, show that domestic sales of antimicrobial drugs for food-producing animals in 2018 actually rose by 9% compared with 2017, to 11,575,059 kilograms of active ingredient.

However, officials said they expected a partial bounce-back following a particularly steep fall in sales in 2017 that they attributed to regulatory changes. The agency emphasized that the overall direction is positive.

"Despite [the] increase, 2018 is the second-lowest year on record and the overall trend continues to indicate that ongoing efforts to support antimicrobial stewardship are having an impact: sales in 2018 are down 21% since 2009, the first year of reporting, and down 38% since 2015, the peak year of sales and distribution," the FDA said in a news release.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when pathogens evolve to tolerate drugs that are meant to kill them. Overuse and misuse of antimicrobial drugs are widely understood by the scientific community to encourage resistance, posing risks to the health of humans and other animals.

In addition to combating disease, antimicrobial drugs have been found to promote growth in livestock, leading food companies to use them for non-medical reasons. Efforts by the FDA and some interest groups to limit the use of antimicrobials to fighting disease culminated in a new rule in 2017.

Eliminating use of the drugs for growth promotion, the rule prohibited over-the-counter use in animal feed and water of "medically important" antimicrobial products — that is, drugs that are used in human medicine — and began requiring oversight by veterinarians.

As a result, U.S. livestock feed manufacturers now need a Veterinary Feed Directive from a licensed veterinarian before adding those drugs to the feed of animals that are used for food.

Full implementation of the rule in 2017 "was a big deal," FDA spokesperson Anne Norris said by email, "and we expected that after that initial precipitous drop in sales/distribution, it was probably not likely that that rate of decline would continue and that there could be a period of recalibration (so to speak) while the market and stakeholders adjust ..."

Norris added, "It'll be much more telling to see how trends play out over time rather than looking at a single year's sales data in isolation."

The European Union banned the use of antimicrobial drugs for growth promotion more than a decade earlier than the U.S., in 2006. Some individual member states have initiated national campaigns related to antimicrobials. The United Kingdom, for example, in 2013 made it illegal for pharmaceutical companies to advertise antimicrobial drugs.

In October, the U.K. Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) released a report that sales of veterinary antibiotics in Britain fell by 9% in 2018 compared with 2017, and by 49% compared with 2014. Total sales in 2018 was 226 metric tons (226,000 kilograms).

Strictly defined, antibiotics are a subset of antimicrobial drugs but the terms often are used interchangeably.

The U.K. sales data includes companion animals, for which sales fell 25% between 2018 and 2017 and by 50% since 2014. The U.S. does not track antimicrobial drug use in companion animals. Federal law requires drug companies to report annual sales and distribution data only for antimicrobials intended for use in food-producing animals, Norris, the FDA spokesperson, said.

Separately, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) reported in October that in 25 European countries that provided veterinary antimicrobial sales data for all years between 2011 and 2017, there was an overall sales decline of 32.5%.

The EMA reports sales of antimicrobial drugs not in total kilograms or metric tons, but in milligrams of active ingredient per "population correction unit," or PCU, a proxy that accounts for the size of the food animal population, including all horses. The amount sold in 2017 was 109.3 mg per PCU, compared with 162 mg per PCU in 2011.

The 25 countries were Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the U.K.

The trends weren't uniform. Nineteen of the countries had sales declines of greater than 5%, whereas sales rose by more than 5% in three countries — Bulgaria, Poland and Slovakia.

The EMA data relates only to food-producing animals because data for cats and dogs were not available from all participating countries.

All three authorities stressed that fluctuations in sales could be influenced by a range of factors, including changes in animal populations or health needs. However, they all maintained, moves to discourage overuse, such as new rules or public awareness campaigns, played some part in driving the reductions in sales volumes.

Precisely how much such efforts contributed to broad decreases in the U.S. is a "challenging work in progress," Norris said, because sales volume alone does not capture the impact of stewardship efforts.

"The agency continues to work with federal, academic and industry partners to obtain more information about how, when and why animal producers and veterinarians use medically important antimicrobial drugs in food-producing animals," Norris said.

The FDA, she added, is planning to publish a report in 2020 that integrates and analyzes other data sources to more fully assess the progress of antimicrobial stewardship efforts, for which she said veterinarians are "the front line" of defense.

"Veterinarians are responsible for ensuring judicious use of antimicrobials," Norris said. "This means using antimicrobials only when they are needed to treat an animal's medical condition, selecting the most appropriate antimicrobial for the intended use, and administering the correct dose with the correct frequency and duration."

In the EU, a spokesperson for the EMA noted that the region's surveillance efforts have grown substantially, from nine countries in 2010 to 31 countries in 2019. "This shows a clear commitment of European countries to promote responsible use of antibiotics in animals," the spokesperson told VIN News.

The EU in 2015 provided stewardship guidance to member countries, while actions are being performed at a country level by veterinarians and farmers, the spokesperson said.

Individual measures that appear to have had a specific impact include the introduction of reduction targets supported in national strategies, farm-level measurement of antimicrobial use and benchmarking, and a requirement to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing prior to using certain drugs.

In the U.K., a nonprofit group called the Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture Alliance (RUMA) has been working closely with the veterinary community to bring usage down, according to a spokesperson for Britain's Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

In 2016, RUMA set up a "targets task force" comprised of one veterinarian and farmer per food-animal group, including cattle, pigs, fish and poultry. The task force has so far had mixed results meeting its 2020 targets across different food categories, as described in detail in a report posted online.

The U.K. government spokesperson said an overall 53% drop in sales of antibiotics for food-producing animals in the four years to 2018, as reported by the VMD, is "a testament to the improvements industry and the veterinary profession have made in antibiotic stewardship, training and disease control."

She added, "The government will continue to work with the sectors to ensure that these successes continue."

Stewardship efforts appear to be having the desired effect, at least judging from the U.K. report, which was unique among the three in that it encompassed measurements of actual resistance to veterinary antimicrobial drugs.

To make the measurements, researchers took samples of digested matter from the cecum, a pouch in the intestines, from healthy chickens and turkeys at slaughter from the U.K.'s biggest slaughterhouses, collectively covering 61% of the country's production.

Among the key findings: They found no resistance to the antibiotic colistin in E. coli isolates collected from turkeys or chickens in 2014, 2016 and 2018. Ciprofloxacin resistance declined in isolates taken from turkeys, to 3% from 8% during that time; and fluctuated between 2% and 4% over the same period in isolates collected from chickens. No or low resistance to third-generation cephalosporins was detected in isolates from turkeys and chickens throughout the period studied.

"The level of antibiotic resistance measured in the indicator bacteria E. coli ... shows further reductions to resistance and represents a marked downward trend," VMD chief executive Professor S. Peter Borriello said in the report's preface.

In the EU, antibiotic resistance data are collected by the European Food Safety Authority. Its

latest report had mixed results and showed at a broad level that antibiotic resistance had not decreased, the EMA spokeswoman said. "This indicates the complexity of antimicrobial resistance, which is not only linked to the antibiotic use in animals," she added.

In the U.S., resistance is measured by the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System, which is composed of the FDA, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Its

most recent findings, for the 2016-17 period, released this November, also were mixed. For instance, for most

Salmonella isolates taken from food and animals, resistance to the antibiotic ceftriaxone declined or remained stable at around 11%. However, in isolates from chicken samples collected routinely at slaughter, ceftriaxone resistance increased from 6.5% in 2015 to 9.3% 2017, and in cecal isolates from turkeys, it increased from 8% to 12% during the same period.