Alan R. Walker photo via Wikimedia Commons

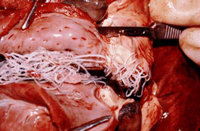

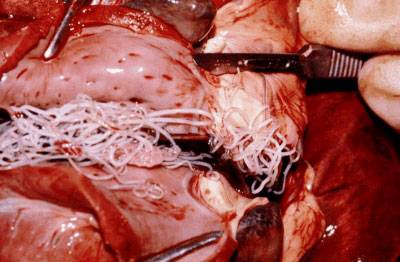

An infected dog's heart shows a cluster of adult heartworms.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is considering changing what it asks of drug makers to demonstrate efficacy of new heartworm preventive medications in dogs, in light of the parasite’s evolving resistance to drugs.

The agency is soliciting public input through Nov. 20 on the design of studies evaluating the effectiveness of prospective heartworm drugs. “Currently, there are gaps in knowledge that prevent the FDA from fully evaluating which alternative approaches are suitable for meeting the standards of effectiveness,” the agency said in a notice requesting comments.

Heartworm is a parasitic worm, Dirofilaria immitis, spread by the bite of infected mosquitoes. It can inhabit the arteries of a dog’s lungs and the heart, causing potentially fatal disease, including congestive heart failure. Preventive drugs kill heartworm larvae.

The FDA review comes as the incidence of heartworm disease appears to have increased in the United States, along with reports of drug resistance. “The need to evaluate alternative approaches is emphasized by the evolving susceptibility of Dirofilaria immitis larvae to heartworm preventatives containing macrocyclic lactones,” the FDA said.

In 2016, the average number of dogs diagnosed per clinic rose by 21.7 percent compared with diagnoses in 2013, according to the American Heartworm Association (AHS). The figure is based upon a survey of 4,705 veterinary practices and shelters around the country.

The survey found cases of heartworm in every state, with concentrations in the South and Southeast. “[T]he top five states in heartworm incidence were Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas and Tennessee — all states that have been in the top tier since AHS began tracking incidence data in 2001,” the group reported.

While veterinarians still consider pet-owner compliance with using heartworm-control drugs to be a crucial factor in combating infections, among veterinarians who reported an increase in cases, 3.3 percent cited insufficient efficacy of the preventives as a factor, the AHS said.

During the last decade, researchers have identified several strains of heartworm that are resistant to a class of drugs known as macrocyclic lactones that are used in all major brands of heartworm control. According to Dr. Chris Rehm, AHS president and a veterinarian in Alabama where heartworm is endemic, there is no widely accepted estimate of how common resistance is.

“The data indicate that there is resistance out there,” Dr. Andy Moorhead, a parasitologist and faculty member at the University of Georgia, said during an interview with the VIN News Service earlier this year. “What we all agree on is there’s smoke on the horizon … the size of the fire is what we don’t know.”

Addressing research limitations

FDA’s current approach to evaluating new heartworm drugs calls for studies in two separate laboratories, using research dogs and recent isolates of heartworm from two separate geographic locations in the U.S.

The agency also calls for a field study conducted in multiple geographic regions where heartworm is endemic, testing the prospective drug in pet dogs.

“Both study types have strengths and limitations,” the FDA states. The limitations are what the agency aims to address.

As an example, it says that using only two isolates of heartworm in the laboratory studies might be inadequate: “[T]he isolates may not accurately represent the current diversity of D. immitis in the United States and may not account for variable susceptibility in the isolates in the field.”

Field studies, while better than laboratory studies in replicating real-world conditions, are rife with uncertainties. For example, “Assurance that individual dogs were exposed to D. immitis larvae during the critical first few months of the study is lacking ...” the agency notes. Therefore, it’s unclear whether a dog that ultimately tests negative for heartworm was protected by the test drug or simply never infected.

Among the questions the FDA would like addressed in public comments are:

- What is an acceptable failure rate of an approved heartworm preventive?

- Could study methods that consider a wider area (beyond an individual animal), such as mosquito testing, forecasting or modeling, reliably be used to determine the likely exposure to infective larvae of dogs at a field study site?

- Can available tests be used to determine an individual dog’s exposure to infective larvae?

- Could a laboratory study be designed to better represent real-world exposure — for example, using live mosquitoes rather than mechanically injecting larvae?

- How might differences in route of administration, dosing frequency, or pharmacokinetic factors impact a prospective drug’s effectiveness?

Further information on the issue and instructions for submitting comments are posted in a Federal Register notice.

This story has been changed from the original to reflect an extension of the comment period by the FDA.