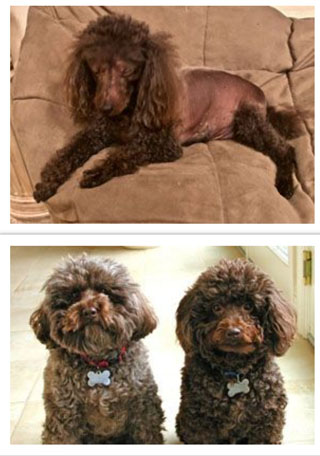

Bailey collage

Photos courtesy of Polly McDonald

Above: Bailey lost fur all around his trunk after being exposed to his owner's topical hormone treatment.

Alopecia is a documented sign in dogs of inadvertent exposure to topical estrogen; however, the cause of Bailey's fur loss was not definitely determined.

Below: As seen pictured with his pal Barnum, Bailey (right) was at one time a fluffy dog.

The middle-aged cat yowled at all hours of the night, marked her territory by urinating around the house and terrorized other cats. She was showing classic signs of being in heat, but that was odd because she was spayed.

This behavior went on for months. The cat's veterinarian, Dr. Carrie Donahue, just wanted to help the cat's owner get some sleep, but she was stumped. Blood tests showed the cat's hormone levels were normal.

Then, in October 2019, three months after the cat's owner first brought her in with this complaint, the cat developed a mammary mass. Donahue began to suspect the cat might have been accidentally exposed to human hormone treatments, a scenario she'd heard of but not seen before.

Donahue gingerly broached the subject with her client. The owner was transitioning from male to female and indeed using a hormone cream. But she assured Donahue that she was very careful to avoid touching her cat when she applied the product.

The mammary mass was removed and Donahue referred the cat to a reproductive medicine specialist. The specialist performed exploratory surgery, searching for ovarian remnants that could be producing hormones in the spayed feline, but the surgery turned up nothing.

Problems with the cat continued for several months. Then, the owner switched to taking hormones orally. With that, the cat's signs of estrus began to wane. Today, a year later, she is back to normal.

While this was Donahue's first experience with such a case, accidental exposure of pets to topical hormones is nothing new. The VIN News Service first reported on the issue in June 2010. Accidental exposures in pets and sometimes in children persist because of the broad use of hormone products — whether to counter symptoms of menopause, as treatments in gender reassignments, or for other purposes — coupled with spotty education on the risk of unintended exposures and how to prevent them.

Transdermal hormone treatments come in the form of gels, creams or sprays that typically are applied to the arms. Users who then snuggle or otherwise touch their pets can transfer the product to the animal, which may absorb it through its skin or ingest it by licking. The products are sold as commercially manufactured drugs and as concoctions prepared by compounding pharmacies.

Awareness is up, but not enough

Dr. Joni Freshman, a veterinary internist with expertise in reproductive medicine, has seen cases of pets unwittingly exposed to their owners' hormone treatments dating to the 1990s. While veterinarians have become more aware of the problem in the past 10 years, Freshman said that in her experience, the caseloads haven't changed much.

Freshman works as a consultant for the laboratory business Antech Diagnostics and for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service. She estimates that she consults on an average of three hormone exposure cases per week for Antech, and occasionally on VIN.

VIN News reported in June 2011 that it had tallied more than 100 instances dating to 2003 of inadvertent topical hormone exposures in dogs and cats reported anecdotally by veterinarians on VIN message boards. Clinical signs in exposed pets include hair loss, skin discoloration, enlarged or unusually small genitalia, enlarged nipples and vulvar discharge. In some instances, pets were exposed to topical testosterone used by men in their households.

For this update, VIN News searched VIN message boards from mid-2011 through July 2020 for references to hormone exposures. The search turned up 53 mentions in cats and dogs. Most cases were in the U.S., some in Canada and one in Malaysia.

Once diagnosed, the problem can be addressed by meticulously avoiding continued exposure. However, because hormones are stored in fat and slowly released into the blood before being excreted, it can take months for their effects to dissipate, depending on the degree and duration of the exposure.

Personal discomfort a barrier to diagnosis

Treatment and prevention

- Use gloves to apply product.

- Apply product to skin the pet will never be exposed to.

- Carefully remove gloves to minimize exposure to hands.

- Discard gloves in closed trash container pet cannot access.

- Store product in location inaccessible to pet.

- Clean any handles touched by hands.

- Wash hands thoroughly.

- After removing clothes worn over treated skin, place clothing immediately into a closed hamper or washing machine to which the pet has no access.

- If bed linens touch skin that has been treated, pet must be barred from the bedroom.

One difficulty of treating or preventing accidental exposure is that hormone therapy use tends to be a deeply personal matter.

Donahue was uncomfortable questioning her client about it. "I just feel like it's a sensitive subject," she said. "And it's not something that a veterinarian who's caring for an animal is just going to bring up."

Freshman recommends asking about topical hormone treatments more than once and in multiple ways to ensure the client understands the question, and answers candidly.

"What I'm really careful to tell people is that I don't care who, I don't care what, and I don't care why. I just want to know if there's a possibility of exposure to topical hormone preparation on anyone's skin," she said.

She suggests veterinarians ask not only about people living in the house but also frequent visitors who come in contact with the pet.

"What I recommend is saying, 'You know, I'm concerned that these clinical signs could possibly be related to topical hormone exposure. Is there anyone that this pet has contact with that might be utilizing hormone-containing products on skin?' … Usually they'll go, 'I don't think so.' And I'll say, 'Well, could you please check? Because I don't want your pet to undergo unnecessary testing or surgery.' "

Freshman recalled that in the very first case she saw of accidental hormone exposure, around 1991, involving a neutered male dog who was losing his fur, she asked at the outset whether the dog had been exposed to hormones. The owner said no. Months later, the client mentioned that the dog had been licking estrogen cream off her belly.

Freshman also recounted a case on which she consulted around 2010, involving two spayed female dogs with swollen vulvas and vulvar discharge. The owner was using a spray-on commercial product called Evamist, and had been assured by physicians and pharmacists that it posed no risk to others after it was dry. Later, the woman's 5- and 7-year-old daughters began menstruating, which, Freshman said, finally caused the woman's physician to take notice.

That same year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert and started an investigation into Evamist after receiving reports of eight children and two dogs that had been accidentally exposed. The main symptom in children — boys and girls alike — was breast development.

After the Evamist advisory, the FDA saw an uptick in the number of adverse event reports in pets, according to agency spokesperson Anne Norris, but "that number did not remain elevated in subsequent years, and FDA has since received one to two reports a year, on average," she said by email.

Responding to questions from VIN News, she elaborated: "In addition, there have been far more reports about dogs than cats. Lastly, reported secondary pet exposures to estradiol [the most active and prevalent form of estrogen] were higher than secondary pet exposures to human drugs containing [the male sex hormone] testosterone."

Reports received by the FDA almost certainly do not reflect all cases. Norris noted that reporting pet exposures to human drugs is voluntary, and that owners and veterinarians might not submit reports for a variety of reasons, including not realizing that exposure has taken place, not knowing how to where to make a report, or owners not taking an exposed pet to the veterinarian.

A pet owner plays detective

Sometimes, pet owners recognize the problem before health professionals.

That was Polly McDonald's experience. In 2012, while using a compounded topical hormone treatment containing estradiol, she noticed her chocolate miniature poodle, Bailey, began to lose fur.

Bailey liked to rest his head in the crook of McDonald's arm, where she applied the cream. She checked the product label. It had a warning about keeping the product away from pets.

McDonald took Bailey to a veterinarian. Tests showed that Bailey had abnormally high estrogen levels. The veterinarian noted McDonald's hormone use, but suspected Bailey's fur loss might be explained by Cushing's disease, a different type of hormone disorder. Various treatments were tried for six months, without resolution.

McDonald called The Hall Center in Santa Monica, California, where she had obtained the compounded hormone treatment, to ask about the likelihood that her dog's fur loss was caused by her product. A center representative replied that staff were aware of similar problems in pets belonging to other clients, and recommended keeping the product away from dogs and small children.

Contacted by VIN News, Beryl Britton, a naturopath at The Hall Center, said the center has been aware of the issue of accidental exposure in pets for at least 10 years. Britton said new patients are warned that the medication can transfer to others through contact with treated skin, and are asked whether they have pets at home. If yes, they are counseled to not apply the product to their arms — which otherwise are an optimal location because the skin is thinner and the product therefore more easily absorbed — but to apply it instead to the abdomen, buttocks or inner thighs, and to wash their hands afterward. Wearing long-sleeved garments can help avoid transferring product applied to the arms, she added.

McDonald began using extra care when applying the cream, washing her hands and using gloves. However, Bailey's fur loss persisted until he was euthanized in 2019 at age 16 for unrelated health problems.

"He was at the point that even after I started being careful, it seemed like it was too late," she said. "He had beautiful, thick hair, and by the time he died, he had just a little bit on his legs. His whole torso was hairless."

Today, McDonald has two new poodles. To avoid exposing them, she wears gloves and applies her cream to her hips and inner thighs. She said the product she uses now contains a label warning that users should not apply it to their arms.

Why more pet owners aren't aware of risks

While some FDA-regulated hormone treatments include warnings about accidental exposure to children and pets, compounded hormone preparations may not.

Compounded products, which are made by pharmacies, are distinct from commercially manufactured drugs, which are subject to approval by the FDA. Compounded medications have enjoyed increased popularity in the face of mistrust of traditional treatments. A study by the National Center for Biotechnology Information published in 2017 found that women were motivated to pursue compounded hormone treatments over typical hormone treatments for reasons including fear about the safety of conventional hormone treatments, distrust of the conventional medical system, perceptions of safety and effectiveness in compounded treatments, and perception of compounded hormones as personalized treatments.

Whereas commercial drugs are subject to regulation by the FDA, oversight of compounded medicines largely is handled by states, where rules vary.

Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel, a founding member and past president of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), has been spreading the word about accidental estrogen and testosterone hormone exposure in pets since she learned about the issue in 2010 after being contacted by VIN News.

An endocrinologist and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, Stuenkel calls hormone transference an area of "intersection" between the disciplines of veterinary and human medicine.

Trying to raise awareness, Stuenkel talks and writes about the risk of exposure at every opportunity. For example, in a presentation in May 2019 to a committee of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine about compounded hormones, she included information about risks of inadvertent exposures in pets and small children. The mention of pets, though, did not make it into the committee's final report on the subject.

The National Academies report, Clinical Utility of Treating Patients with Compounded "Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy" calls for much more limited use of such products. It recommends, among other things, restricting prescriptions of compounded hormones to patients who have a documented allergy to, or need a different dosage form than is available from, existing FDA-approved drugs.

Prescriptions for compounded hormone therapy should not be motivated by "patient preference alone," the report authors advise. They also recommend increased oversight of the compounding industry.

Finding solutions

Stuenkel believes that heeding the report recommendations could help solve the problem of pet exposures. "The National Academies has come out with strong recommendations, really good ideas, things that I think a conscientious practitioner can do right now," she said.

Her advice to medical colleagues is: "Tell your patients that compounded hormone therapies are not FDA-approved. Give them a copy of the boxed warning of an FDA-approved preparation that is required to list risks and benefits. Don't use the compounded preparations unless there is a documented need."

What about accidental exposures to FDA-approved products? "I think if [patients are] cautioned when it's prescribed and if their labeling includes cautions, that's ideal," Stuenkel said.

And for veterinarians, she advised, "I think it's reasonable to just ask [owners] if it is possible that the pet could have been exposed to topical hormone therapy. Nobody wants to hurt their beloved pet!"

Freshman, for her part, believes better labeling would go a long way.

"What I would like is for all products containing estrogen that are dispensed from a pharmacy to a person to have a warning with them about topical exposure to pets," she said. "I think that's the best way to deal with it, because that's going to come right with the product."