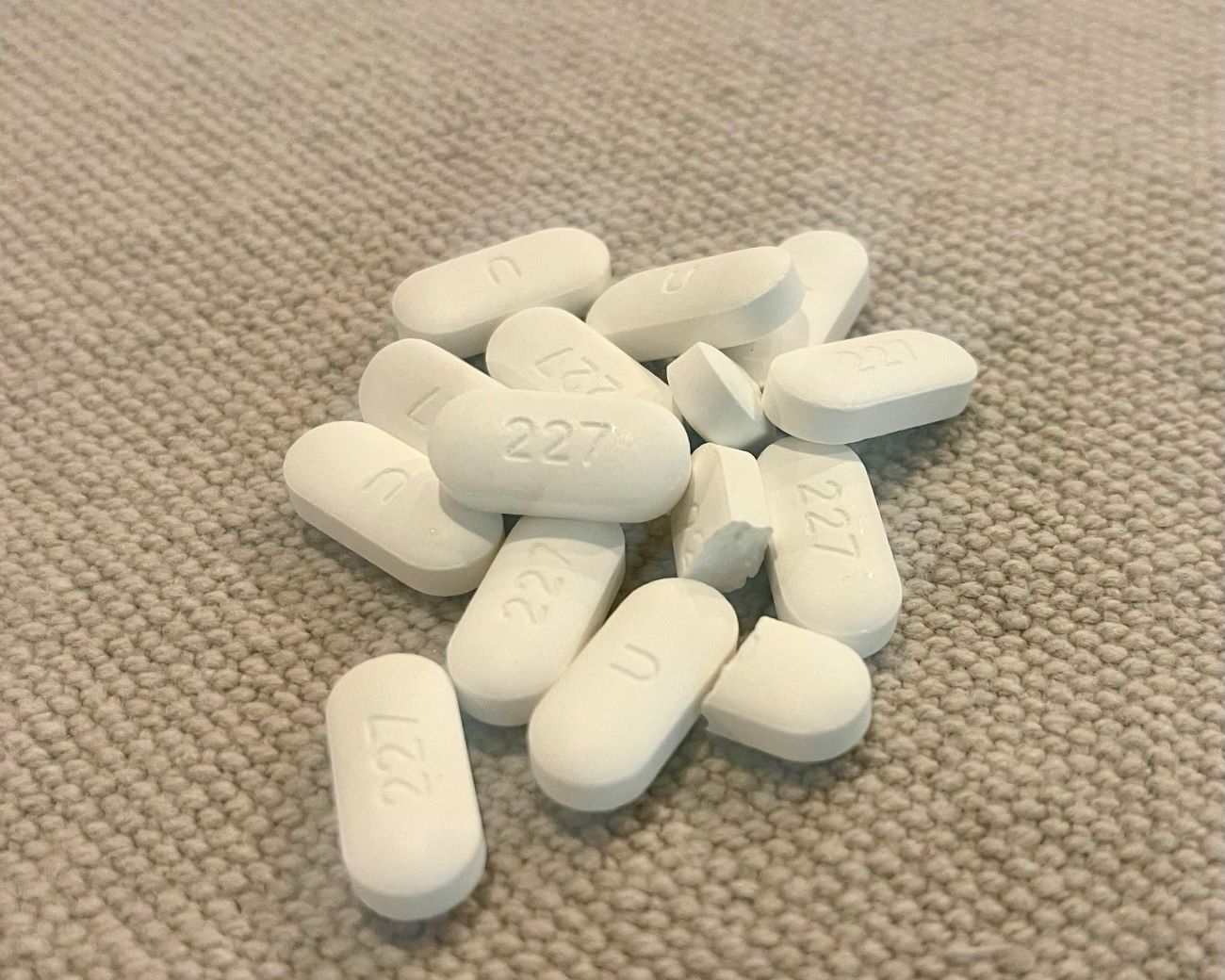

500 mg metronidazole

VIN News Service photo

A growing body of studies suggests that metronidazole, long a standard treatment for diarrhea in dogs, doesn't necessarily speed recovery and may even hinder it.

The scenario is all too familiar to most veterinarians: A dog with diarrhea is driving its owner crazy. It's pooping all over the house. It's whining all night to go outside. The client all but begs the veterinarian to do something (anything!) to make the problem disappear.

For years, the go-to move was to prescribe an antibiotic, usually metronidazole, to speed recovery from a condition that, in most instances, eventually resolves on its own. But mounting evidence indicates that antibiotics aren't the quick fix for acute diarrhea that they've been cracked up to be, prompting veterinarians to reassess how they handle one of the most common presentations in clinical practice.

The issue isn't just an apparent lack of efficacy. Metronidazole might negatively alter the microbiome — the community of microorganisms living in an animal's gut — for weeks and even months after it's been given, some studies show. Moreover, veterinarians are being urged to use antimicrobials sparingly to combat drug resistance, which occurs when pathogenic microbes evolve to withstand treatments meant to kill them, endangering the health of humans and other animals.

"It's a huge issue in terms of antimicrobial use," said Dr. Andy Kent, a specialist in small animal internal medicine in Birmingham, England. "The more common a condition is — just think about how many consults take place around the world every day for dog diarrhea — the more you can make a real impact tackling antimicrobial resistance."

Acute diarrhea commonly is defined in the scientific literature as a loose bowel movement lasting one to two weeks but often resolving in two days or fewer. Common causes include dogs eating something they shouldn't — such as when they scavenge — sudden changes in their diet, or stress. Mucus or blood may be present, but the condition usually is uncomplicated, with no signs of serious illness such as severe hemorrhaging or weight loss.

The VIN News Service examined eight studies published since 2019 that assessed the efficacy of antibiotics, most commonly metronidazole, in treating acute canine diarrhea. With minor exceptions, they overwhelmingly suggest that antibiotics are either ineffective or no more effective than feeding a diet of highly digestible foods, such as white rice and boiled chicken breast, and perhaps a probiotic. (Evidence that probiotics work is limited, however).

Two of the eight studies found that fecal consistency improved after the use of metronidazole, but one of those studies had no placebo group. The other showed that dogs given metronidazole recovered, on average, 1.5 days faster than those who weren't. That study involved a small number of dogs — 14, including the controls. And the researchers said the results didn't establish whether metronidazole should be a first-line treatment because other factors needed to be considered, such as its negative impact on the gut microbiome and the potential effectiveness of a simple change in diet.

The other six studies indicated that antibiotics likely are ineffective or no more effective than a modified diet, including one published last year and conducted by veterinarians at The Ohio State University that found dogs given metronidazole took longer to recover than those that weren't.

The latest of the studies, published last month, was conducted by veterinarians at the Royal Veterinary College in the United Kingdom and based on nearly two million clinical records submitted to its VetCompass program. The researchers drew on a random sample of 894 dogs with acute diarrhea, 355 (39.7%) of whom were given antibiotics and 539 (60.3%) who weren't. The likelihood of clinical resolution in the dogs given antibiotics was 88.3%, compared with 87.9% in dogs not given antibiotics, a statistically insignificant difference.

"We continue to have more and more evidence to support the fact that antimicrobials don't really help or don't significantly speed up the time that it takes for diarrhea to resolve," said Kent. "Unfortunately, despite that fact, people still keep giving out antibiotics."

Confirmation bias can be a factor, he believes: A veterinarian administers an antibiotic, the dog gets better, and the veterinarian attributes the improvement to the antibiotic.

Dr. Sherri Wilson, an internal medicine specialist near Seattle, concurs. "It turns out, when you do the research, [you find that] the diarrhea gets better in two or three days on its own, anyway," she said in an interview. "So when there's a process like that, where everything seems to work, it usually means nothing is working. It's just getting better."

Wilson and Kent also are internal medicine consultants for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News.

Profession split as practitioners count on experience

The question of whether to treat or not with drugs is sparking vibrant discussion on VIN message boards. Opinions fall on a continuum ranging from veterinarians who stopped years ago using antibiotics for acute diarrhea to those who remain convinced of their efficacy and, as one practitioner quipped, would need the metronidazole to be pried from their cold, dead hands.

Veterinarians who swear by antibiotics say they've used them successfully on countless occasions, often maintaining that the science suggesting they don't work isn't exhaustive and pointing out that studies have variations and limitations in methodologies. Veterinarians who don't use antibiotics counter that the studies, although imperfect, are more reliable than anecdotal evidence.

Among the many still using antibiotics is Dr. Elizabeth Tonsich in St. Johns, Florida. She reasons that clients typically wait a day or two after the diarrhea starts before consulting a veterinarian. "If the diarrhea was self-limiting, then the clients would not have brought the dog in," she posted on a VIN message board. Dogs, she said, usually recover rapidly after receiving the drug, making for "very happy, appreciative" owners.

Aware of the research about metronidazole, Tonsich has tried a probiotic for mild cases. "But, as I said, most cases I see are the bad cases, so I still prefer to use [the antibiotic]," she said later in an interview. Tonsich said she thinks she'll continue to experiment with giving only a probiotic in mild cases and limit her use of metronidazole more over time. "If I am successful with my treatments, then I will continue to use it less."

Dr. Joe Waldman in Calgary, Alberta, said he reserves metronidazole for more severe cases of acute diarrhea that involve the large intestine (also known as the large bowel), which tend to have clinical signs such as a higher-than-usual frequency of defecation, urgency and accidents and the presence of blood or mucus. He'd like to see more studies take different manifestations of diarrhea into account.

"The value of a study is that it needs to reflect the real world application of that treatment," Waldman wrote on VIN. "If the study doesn't align itself with the way the treatments are most commonly used, then what is the value of the study?"

Each of the studies considered by VIN News applied different inclusion and exclusion criteria, although all tended to exclude dogs displaying serious conditions, such as sepsis or parvovirus, or severe clinical signs, such as weight loss. Some excluded dogs with blood in their feces, while others did not. The research by the veterinarians at Ohio State, for instance, included only dogs with large-bowel diarrhea that exhibited "two or more" of a selection of clinical signs: blood, mucus, watery consistency of feces, difficulty defecating, increased frequency of defecation, small-volume defecations, or tenesmus (frequent urge to defecate without being able).

Concerns about the studies' inconsistencies and shortcomings are valid, according to Dr. Brennen McKenzie, an advocate of evidence-based veterinary medicine who has written about acute diarrhea in his SkeptVet blog. "The evidence is limited and flawed and not universally applicable," he posted to a VIN discussion in April. "However, it is the best evidence we have so far, and it is pretty consistently discouraging [using antibiotics]."

McKenzie contends that "the real sticking point" is that studies showing that antibiotics don't work challenge years of tradition that often is based on anecdotal evidence. "While the controlled research evidence is scant and flawed, it is far superior to such uncontrolled personal observations," he said. "And the aggregation of such anecdotal experiences by the thousands does nothing to make them more likely to be true."

Dr. J. Scott Weese, a zoonotic disease expert at the University of Guelph's veterinary teaching hospital in Ontario, is similarly dubious about the efficacy of antibiotics to treat canine diarrhea. "We're programmed to want to ‘do something,' even though doing nothing is often the best approach," he wrote last month in Worms & Germs Blog. "Try thinking about it this way: when you or your child gets diarrhea, do you rush to the doctor? No. If you're otherwise healthy, you wait it out and it almost always gets better on its own."

Weese said the latest research from the RVC is "an important addition to our knowledge about treating diarrhea in dogs," and offers additional support to veterinarians taking the wait-and-see approach.

Research since 2019 on efficacy of antibiotics for diarrhea in dogs

Sending clients home empty-handed is a challenge

Doing nothing is easier said than done. Some practitioners who posted to VIN indicated that they reach for antibiotics largely to placate demanding clients.

Wilson, the internal medicine specialist, agrees that keeping clients happy is hard. "That's the huge hurdle here," she said. "If this is your dog that's pooping in the house, it's hitting the walls or whatever, and you're getting up all night, you want a pill, whether it works or not."

She suggested veterinarians consider handing clients a leaflet that explains why antibiotics are not always appropriate. "It could say that it has been shown in multiple studies that metronidazole doesn't affect the time to resolution of acute diarrhea — and it can have negative consequences on your dog's gut health," she said.

For his part, Kent suggests practitioners consider playing educational videos in their waiting rooms, such as those produced by the European Network for Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Treatment. Another option, he said, is delayed prescribing. Used commonly in human medicine, it entails giving clients a prescription that can be filled in a week or two if needed.

Both veterinarians acknowledge there will be instances in which a patient goes on to develop chronic diarrhea or has a serious complication that requires more intensive action that may or may not involve antibiotics. "Even though 99% of cases might resolve on their own, another 1% will still have diarrhea in three weeks' time," Kent said. "Some of those owners will be disgruntled that you didn't do more at the start."

Such situations are an unavoidable reality of practicing medicine, he said: "We haven't got a crystal ball that can predict the evolution of every case, so I think that it's a matter of trying to communicate with clients and getting them to understand the kind of inherent challenges of managing unpredictable situations."

Wilson suggests veterinarians could inform clients of clinical signs to watch for that indicate more serious disease. "You could say, for instance, if your dog is not resolving after four or five days, we want to hear about it. Or if they're actively declining — they're not eating, they're vomiting and things have gotten much worse — don't just sit there."

For cases involving more serious disease, a typical dose of metronidazole might not be enough to treat the problem, anyway. Take an infection with the parasite Giardia. "We don't use metronidazole very much for Giardia because you have to use a higher-than-normal dose, and it can be a scary dose — you can get neurological signs," Wilson said. "We would usually use fenbendazole, [which is] even more effective than that high dose of metronidazole."

Should a dog appear to be particularly ill or its condition worsen, Wilson added, they could be tested for parasites, such as giardia or hookworm, or other conditions that cause diarrhea, like parvovirus. Kent notes, though, that some diseases that cause diarrhea, such as Salmonella or Campylobacter infections, also often resolve without antibiotics.

He observed that veterinarians increasingly are moving away from antibiotics for chronic diarrhea because of the drugs' impact on gut flora. "Many dogs that have chronic diarrhea have a deranged gut flora to begin with," he said. "If we throw antibiotics into the mix, sometimes we just make their gut flora even more deranged."

Probiotics may hold promise, but evidence is scanty

The extent to which antibiotics can hinder rather than help is becoming clearer as cutting-edge DNA sequencing technology enables scientists to better map and understand the function of the microbiome.

Antibiotics can kill gastrointestinal microbiota that protect hosts from a range of pathogens and assist in digestion. Metronidazole specifically can have "long-term detrimental implications" for the gut microbiome, particularly in relation to bile acid dysfunction, according to the RVC paper.

Conversely, the potential for probiotics — microorganisms introduced to the body for their apparent benefits — to speed resolution of acute canine diarrhea is unclear. One of the eight studies reviewed by VIN News, for instance, found that the fecal consistency of dogs given a probiotic recovered 1.3 days faster than placebo. By contrast, the recent RVC study found that dogs given nutraceuticals — a broad term covering a range of supplements including probiotics — didn't recover any faster than control.

"We're still in the infancy of understanding probiotics and what could be the right ones to use," Wilson said. Studies indicating they can assist gut health, she observed, often have been sponsored by product manufacturers. Still, she believes they are reasonably safe to use and tends to recommend probiotics for dogs with chronic diarrhea.

Kent agreed that while the evidence for probiotics is "very limited," they appear to be safer than antibiotics. He cautioned, "We don't understand enough yet about in which situations probiotics might be helpful and which strains of probiotics will work."

He noted that a limitation of the RVC study, which indicated probiotics don't work, was that it did not distinguish among probiotic formulations.

"Is it possible that there are some probiotics that are better than others? I think it's certainly possible, but that's where we need a lot more evidence," Kent said. "I think our understanding of how probiotics and antibiotics affect the microbiome and dog diarrhea hopefully will only increase over the coming years."