For independent practitioners, veterinary group purchasing is akin to arming David with a bigger, better slingshot for combat with Goliath — if Goliath was a large hospital group.

As part of a group purchasing organization, known as a GPO, single and small-group practice owners unite to negotiate better pricing and terms from distributors, manufacturers and service providers. That kind of buying power can cut costs for independent practices in ways similar to the business advantages automatically enjoyed by corporate mega-chains.

The GPO pitch has resonated with solo and small-group practice owners. As practices increasingly come under consolidated ownership, more and more independent practices are joining one, two or more organizations. According to a Brakke Distributor Effectiveness Study, 31.8 percent of practices belonged to a GPO in 2017, up from 19 percent in 2015. In a biannual survey, the animal health research and consulting firm asked 1,000 companion animal veterinarians to evaluate the performance of their distributors and included questions about GPO membership.

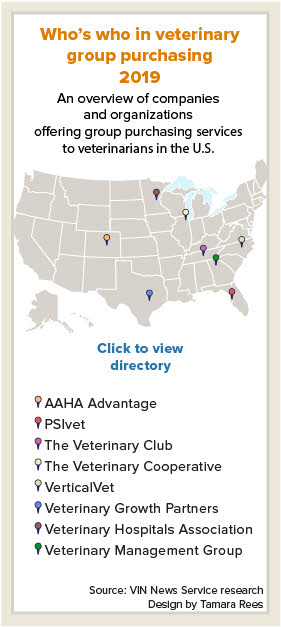

Since the VIN News Service began covering group purchasing activity in 2013, GPOs' reported combined membership more than doubled to more than 19,000, even as the number of GPOs shrank from 10 to eight. During the past six years, three new GPOs launched, three established GPOs merged with others, and at least two went out of business. Also, while half of the GPOs operating in 2013 were regional, today all but one is national.

In other transformative developments, big finance is shaking up what was once a veterinarians-only affair. In 2016, publicly traded Henry Schein Inc. bought Purchasing Services Inc., one of the nation's largest and oldest GPOs. Last year, Veterinary Growth Partners, a newcomer to group purchasing, became part of Pathway Vet Alliance, which is partly owned by a major private equity company.

Along with the ebb and flow of industry players, the structures of GPOs are changing. Several of the companies interviewed for this story prefer not to be called GPOs. Nowadays, negotiated discounts and streamlined purchasing rarely stand alone. Instead, group purchasing most often is one offering among a raft of services for members. Now GPO hybrids offer business and/or clinical education, marketing support, practice-performance analytics and more.

(The Veterinary Information Network, an online membership community for the profession and parent of VIN News, offers some of the same services as companies and organizations in this story, including continuing education, practice metrics, and tools for client communications and practice management.)

GPOs predicted to keep growing

In interviews with VIN News, officials with several GPOs estimated that at least half of all U.S. practices participate in some form of group buying either by belonging to a GPO or as members of a corporate practice chain.

VerticalVet president John Wagoner predicts the proportion of participating practices in the country will climb to 55% to 60% before the end of the year. He said that in Europe, nearly 100 percent of practices either belong to a GPO or are owned by a large corporation.

Determining just how many practices are in GPOs is complicated, however. Reported membership counts can't be independently verified. GPOs keep most information confidential, including the identity of vendors, pricing, agreements and profits, and members sign non-disclosure agreements. In addition, it's not simply a matter of adding up reported membership totals. Practices often belong to more than one group as a way to hedge their bets or because they want to do business with a variety of vendors that aren't all represented by a given group. Only Georgia-based Veterinary Management Groups, a collection of study groups that offers some group purchasing, bars members from belonging to other GPOs.

Membership size matters, GPO officials say. The bigger the GPO, the better the vendor deals. Accordingly, entities that offer group purchasing are getting larger. In 2013, only two of 10 claimed to have more than 1,000 member hospitals; the largest claimed 10,000 practices enrolled, of which 3,000 were active. Today, four GPOs say they have from 3,000 to more than 5,000 member hospitals. They are PSIvet, The Veterinary Club, The Veterinary Cooperative and Veterinary Growth Partners.

Moving away from veterinarian-owned, -operated

In the 1980s, buying groups were started by practicing veterinarians banding together to improve their negotiating power, as was the case at PSI (the original name of PSIvet), and two that are now defunct — Professional Veterinary Products and Veterinary Purchasing, Inc. The Veterinary Hospitals Association's GPO grew out of a conclave of Midwest veterinarians who banded together to establish their own crematorium.

Over time, non-veterinarians entered the mix from sectors including data analytics, investment banking, human health care — where GPOs are ubiquitous — and veterinary distribution.

In 2016, PSI (now Professional Services for the Independent Veterinarian, or PSIvet) was purchased by Henry Schein Animal Health (HSAH), one of the three largest distributors of veterinary supplies and practice management software in the country. In February, HSAH merged with Vets First Choice, an online pharmacy and prescription management platform, forming a new entity called Covetrus.

Schein's purchase was one of a series of consolidations among GPOs in the past few years that transformed regional groups into national entities. In 2015, Veterinary Purchasing Group (VPG) acquired the Veterinary Group Purchasing Organization. In 2017, PSI acquired VPG. That same year, The Veterinary Cooperative accepted members of Veterinary Purchasing Inc., a veterinarian-owned distributorship that went out of business.

Schein's purchase of PSI wasn't publicly announced, though it was the subject of rumors in the industry for some time. The first public confirmation of the purchase appears to have been in materials provided by Covetrus for investors in early February.

Because agreements with distributors comprise a substantial share of GPO business, the idea of a buying group under the same roof as a leading distributor raised questions among stakeholders: How can PSIvet negotiate the best terms on behalf of members if the company is limited to working only with Covetrus? And from the perspective of purchasing group rivals, how can they possibly compete with PSIvet in negotiating with Covetrus?

"They are owned by a distributor. There can't be a neutral playing field," said VerticalVet's Wagoner, one of several leaders from competing GPOs who questioned the fairness of this move.

PSIvet resident Patrick McCarthy countered: "There will always be naysayers." He told VIN News that PSIvet, while a subsidiary of Covetrus, is "a separate and independent division... You won't find us branded as Covetrus or anything like that. We are PSIvet."

McCarthy cast the relationship as the best of both worlds — well-resourced and well-connected to the benefit of veterinarians; yet free to act independently.

However, when it comes to all-important distributor agreements, McCarthy said, PSIvet does obligate its members to make 80 percent of their distributor purchases from Covetrus. But, he added, PSIvet won't be unreasonable if members want to make some purchases from outside vendors.

"It may be that one of our members likes the representative from an opposing company," McCarthy said. "We're not going to kick them out for that. We educate them. We create benefits."

In public statements, on its website and in its new name, PSIvet is putting "independent" front and center, and McCarthy is adamant that the company is committed to independent veterinarians.

"Ultimately, independent veterinarians will need a voice and they will need the ability to go out and defend themselves using the same tools and same tactics that the big entities are using," McCarthy says. Those tactics go far beyond discounts to include online and in-person business education and real-time practice performance analytics, which includes benchmarking against the 5,000-plus practices in PSIvet.

Is 'GPO' a dirty word?

PSIvet is part of a trend of GPOs acting as more than GPOs. The Veterinary Cooperative has expanded into business support and continuing education over the past seven years. Cooperative president Allison Morris said her group prefers the term "cooperative" rather than "GPO." VerticalVet and Veterinary Growth Partners launched in the past decade with a range of practice support services, group purchasing being just one among many.

Dr. Jasen Trautwein, co-founder of Veterinary Growth Partners, is "offended" when his company is called a GPO because he takes issue with the model. He said traditional GPOs create an us-versus-them situation that pits vendors against each other and squeezes their margins in "a race to the bottom." He describes VGP's approach as finding common interest and alignment with select industry partners "to help veterinarians grow their business … because ultimately if veterinarians aren't successful … industry isn't successful, either."

VGP is unique among GPOs, GPO-hybrids or whatever the descriptor, in that it is owned by a company that owns veterinary hospitals. Last year, VGP was folded into Pathway Vet Alliance.

Trautwein founded Pathway, beginning with his own clinic in 2003, and grew it to more than 30 clinics by 2016. At that time, Morgan Stanley Global Private Equity acquired a majority stake in the company. The funding fueled the purchase of more than 100 practices as part of an "acquisition growth strategy," according to a story in the (Austin) Statesman.

Today, Pathway has more than 200 practices in 33 states. With an expanded number of veterinarian shareholders, Morgan Stanley's portion of the company has since dropped below 50%, according to Trautwein.

All Pathway hospitals are VGP members, but not all VGP members are Pathway hospitals, and the connection between the companies is not identified on either website.

The relationship is "not hidden but it's not overt," Trautwein said. "They are sister companies each with a different leadership team."

Loyalty requirements may be coming

Practice owners and managers talk openly about belonging to multiple GPOs so they can comparison-shop and get access to a variety of vendors.

That habit poses challenges for GPOs. Most make the bulk of their income from fees paid by participating vendors based on member purchases. If members belong to several GPOs with overlapping vendor deals, a particular GPO may not receive credit for a sale. Less activity per member affects a GPO's bottom line and can lead to less favorable terms from vendors or even vendors dropping a GPO.

"Groups with more members and active purchasers gain more traction with manufacturers and distributors," The Veterinary Cooperative's Allison Morris told VIN News. "Split loyalty hurts all groups." In cases where vendors have agreements with multiple GPOs, Morris encourages members to select one GPO that all purchases are tracked through.

GPOs have three ways to stem dilution: They can establish purchase-level minimums, they can establish loyalty requirements or they can do both.

Only PSIvet has a stated purchase-level obligation. It asks members to commit to purchasing 80% from the GPOs' preferred vendors.

Several GPO leaders said loyalty requirements are coming. For the moment, only VMG insists on loyalty. However, many expressed a desire that practices make a commitment.

"We don't want deadbeats in our group. They hurt the overall growth goal of the company," VerticalVets' Wagoner said. "We want to be selective for members who are really interested in being a community collaborative."

Several GPO heads agree that loyalty requirements and/or purchasing minimums will likely result in further consolidation of the GPO sector.