Midwest grads

Facebook photo

Borrowing money to attend veterinary school is nothing new, but the scale is escalating. A greater proportion of new graduates in 2018 owed $250,000 or more compared with previous classes, an American Veterinary Medical Association survey found. The AVMA attributed the uptick in part to Midwestern University's new veterinary program, the nation's most expensive, with tuition at $59,454 for the 2017-18 academic year. Midwestern graduated 87 students last May (pictured).

The typical veterinary graduate entered a small animal practice in 2018 earning at least $80,000 a year in addition to paid vacations, stipends for continuing education and health-care benefits. She may have received a signing bonus.

At the same time, the size of her student debt rivaled that of a home mortgage. The average debt of a class of 2018 veterinary-school borrower was $183,014, roughly 10% greater than that of the previous year's graduating class. What’s more, the proportion of those with the heaviest debt burdens — $250,000 or greater — ballooned to 19%. Again, that's an increase from 2017, when 13% of all graduates of U.S. programs entered the workforce with that kind of burden — a burden that compounds as interest grows, until the loans are paid in full.

The 2018 debt figures are among a bevy of findings from the American Veterinary Medical Association’s annual survey of fourth-year students at U.S. veterinary medical programs. The results, published May 1 in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, reflect responses from 2,733 of 3,142 students. They received the web-based survey roughly four weeks before they graduated in spring 2018.

Bridgette Bain and Matthew Salois, AVMA economists who authored the report, attributed the uptick in debt, in part, to the survey’s inclusion of graduates from Lincoln Memorial and Midwestern universities. Both private institutions graduated their first classes in 2018. Tuition at Midwestern's veterinary school is the nation's priciest: $59,454 during the 2017-18 academic year, not including fees, books and living expenses. At $42,252 a year, LMU's tuition ranks 12th among U.S.-based programs, according to a cost of education map by the VIN Foundation.

"…[T]he mean educational debt reported by respondents of those first graduating classes (class of 2018) was higher than the mean educational debt reported by respondents from most of the other 28 veterinary schools," the report's authors said.

With the addition of two new programs, the authors added, interpretations about changes in salary and debt in 2018 "should be made with care."

Jobs, salary breakdown

The rise in student debt outpaced growth in employment earnings, which rose moderately in 2018. The mean full-time starting salary for new graduates was $81,571 in 2018, not counting those pursuing advanced education. The figure was weighted to account for salary disparities in geographical regions and cost-of-living variations between urban and rural practices. It represents a 7.1% increase from 2017, in which the mean full-time starting salaries for new graduates was $76,130.

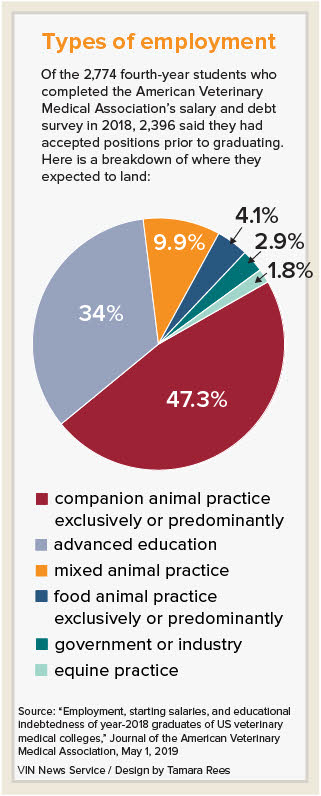

Among those in the 2018 class who accepted offers, 66% accepted full-time positions in private or public practice, while 34% opted to continue their education. Of those who planned to work in private practice, most planned to enter companion animal medicine, followed by mix animal practice, food animal practice and equine medicine.

The report noted that rural veterinary medicine often pays less: "An increase in the number of veterinarians who accept more jobs in rural areas may depress the overall mean starting salary of veterinarians, even if salaries have increased in both rural and urban areas."

Twenty-six of 41 respondents who accepted offers in full-time food-animal exclusive practices would earn $80,000 or more a year; the rest reported salary offers $10,000 to $20,000 less. By contrast, the vast majority of those who accepted jobs in companion animal practices reported offers of $80,000 or more a year. Just 17 of 916 respondents entering companion animal practice reported accepted offers of less than $50,000.

'Incomplete, misleading picture'

Dr. Tony Bartels would like to see AVMA debt figures presented in as much detail as the figures about income.

A student-debt expert with the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service, Bartels said that, for example, the survey does not include debt data for the 929 Americans who graduated from international programs in 2018. "We still have some significant differences in other available data, which makes understanding the debt of newly minted veterinarians difficult to understand," Bartels said by email.

By example, he pointed to data released earlier this year by the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, which collected information from the same U.S. programs included in the AVMA's survey. However, AAVMC went a step further and also collected information from the five Canadian programs and 11 international institutions attended by 929 U.S. students who graduated in 2018.

AAVMC puts the mean institutional indebtedness for that collective cohort at $174,117. Unlike data from the AVMA, the AAVMC's figure represents indebted graduates only, and includes only debt accrued during matriculation in veterinary professional programs — not undergraduate degrees, as well.

By omitting Americans graduating from foreign programs, the AVMA survey results reflect just 67% of all 2018 graduates eligible for federal student aid, Bartels said. He points out that some foreign programs are heavily attended by Americans and cost as much as or more than Midwestern to attend.

"There is still no Ross, no SGU, no RVC London — all three of those are in the top 10 of AAVMC median institutional reported debt for 2018 graduates," he said, referring to Ross and St. George’s universities, both in the Caribbean; and the Royal Veterinary College in London.

Veterinary education at international and private programs is pricier than that of state-subsidized institutions. Ross, for example, reports that a typical veterinary student accumulates $302,104 of student debt by the time they graduate — roughly $120,000 more than the mean debt calculated for graduates of U.S.-based programs.

Adding foreign-trained Americans to the AVMA's survey pool isn't the only way the AVMA report might more accurately reflect new graduate debt, Bartels said. He suggests raising the survey's debt ranges beyond "$250,000 or greater."

"[A]ll but nine of the AAVMC-member institutions had schools with students who have max debt greater than $250,000, with the top one reported at $440,000," Bartels said. "... Those missing folks from higher-priced schools and the $250,000 category are among the most obvious omissions from the veterinary student debt picture."

Asked to address Bartels’s critiques, the AVMA said they could not respond immediately. Sharon Granskog, assistant director of media relations, noted that the May 1 JAVMA article merely reports the survey results.

"Your questions would require a much more detailed analysis," she said.

Editor's note: This article was changed from the original to clarify the AVMA's response.