Say "shortage of veterinarians" and duck while debate ensues. The topic is historically fraught and often contested, especially when it comes to the overall supply of general practitioners. But in one area of the profession, there are few doubts of a shortage: specialty medicine.

Say "shortage of veterinarians" and duck while debate ensues. The topic is historically fraught and often contested, especially when it comes to the overall supply of general practitioners. But in one area of the profession, there are few doubts of a shortage: specialty medicine.

The root of the pinch is the limited number of residencies — training required of all aspiring specialists — relative to the demand for specialists. In university teaching hospitals, where the majority of residencies take place, tight finances often constrain the number of slots.

Moreover, in some instances, there are not enough specialists to do the training. In a negative feedback loop, specialists in academia are being lured away by higher pay and promises of better work-life balance in the private sector, where demand for specialists has exploded as pet owners are increasingly willing to pay for specialized medical care for their furry family members.

These conditions have opened the door to greater industry involvement in training specialists: Today, veterinary companies increasingly fund resident training at universities and run residency programs of their own.

The trend is viewed with cautious pragmatism. The desire to expand training opportunities and the belief it can be accomplished well are weighed against concerns that industry-funded training agreements could lock veterinarians desperate to specialize into disagreeable working commitments or that partnering with industry might be a first step toward diluting rigorous training standards.

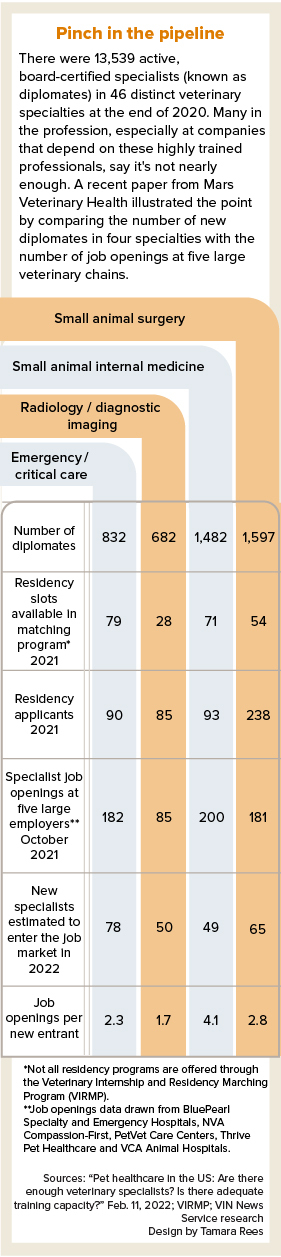

Mars Veterinary Health, the world's largest veterinary company, released a report earlier this year that aimed to quantify the shortage. The report looks at four specialties, those with the greatest number of diplomates directly active in companion animal practice: small animal internal medicine, surgery, emergency and critical care and radiology/diagnostic imaging. Diplomate is a term for a doctor who is board-certified in a specialty.

Written by Dr. James Lloyd, a veterinarian and economist, the report states that if five large corporate practices alone — BluePearl Specialty and Emergency Pet Hospitals, NVA Compassion-First, PetVet Care Centers and Thrive Pet Healthcare and VCA Animal Hospitals — were able to hire every specialist certified this year, they still would not come close to filling their open positions. And that doesn't account for demand at other companies and in academia.

Changing attitudes about sponsorship

It's a sign of the times that when Dr. Joshua Stern, associate dean for veterinary medical center operations at the University of California, Davis, was asked to comment on the role of industry in training specialists, he was in the middle of considering multiple proposals from veterinary companies wanting to fund residents at the prestigious teaching hospital.

Sponsored residencies are created when a third party, such as a diagnostic company or a large specialty practice consolidator, provides funding to a school to cover a residents' salary, benefits and other agreed-upon expenses. In exchange, the resident, after completing training, works for their sponsor for a predetermined term, often three to five years. Such arrangements typically add a training slot or slots that the university couldn't otherwise afford, which is one reason sponsored residencies are proliferating.

No organization collects figures for the number of sponsored residencies offered each year, but most professionals involved in the training of residents who spoke to the VIN News Service said that industry-sponsored residencies are on the increase, with a spike in the past few years.

For example, Thrive Pet Healthcare, which has around 350 hospitals across the country, went from sponsoring four residents at two universities last year to sponsoring 20 at nine universities this year. MedVet, with 30 emergency, urgent care, ophthalmology and multispecialty hospitals around the country, has offered residency training itself for many years, but in 2020, it sponsored a resident for the first time. Since then, MedVet has funded a total of five residents at two teaching hospitals.

UC Davis currently has multiple corporate-sponsored residents training in radiology, and is weighing whether to accept sponorships in other specialties. That would be a big shift for the training program, which, with more than 100 residents, is one of the largest in the country.

It would also be a big shift for Stern, who long has been leery of these arrangements. He has worried that contractually binding veterinarians to work for a particular business after their residency can result in unhappy servitude. He knows of residents who wanted to stay at the programs where they trained and regretted the post-residency commitment they made. Stern said that tendency to affiliate during training is one reason companies embrace sponsored residencies. “They've started to get creative about how they could ensure that they have a pipeline of specialists coming to them at some point,” he said.

He also believes training sponsored residents alongside regular residents creates an imbalance of possible futures — one predetermined, the other open-ended. "You have these people who are experiencing the same training programs, but the truth is, they're not experiencing it in the same way," Stern said. "And so some of us are concerned about that."

However, Stern's thinking is evolving. He said he sees how a sponsored residency might improve conditions for residents in the program overall. For example, adding a spot might provide a colleague for a lone resident, or spread on-call shifts among four residents rather than three.

"I'm entertaining [additional sponsorships] principally because I believe we have some services where resident quality of life and success in the training program could go up if numbers of trainees went up,” Stern said.

“In an ideal world, there would be enough money to train people and let them choose whatever they wanted,” he added. “But it's not an ideal world on many levels. So here we are, and [companies] have created a solution that does work for many people. I think, honestly, it's more about us catching up in our thinking. Truth be told, most residents go into private practice, anyway. So what's the real harm in having some of them have a program funded that otherwise wouldn't have existed?”

How sponsorship works

Veterinary companies aren't the only outside entities sponsoring residents. The U.S. Army funds residencies for active-duty Army Veterinary Corps officers in emergency medicine and critical care, equine medicine, internal medicine, laboratory animal medicine, radiology, surgery, behavior and pathology. Unlike privately sponsored residents, Army veterinarians are paid directly by the federal government and receive salary and benefits based on their rank, and their service obligations are determined by the length of the training programs, according to U.S. Army spokesperson Sgt. 1st Class Anthony Hewitt.

A veterinary school will sometimes sponsor a resident at another institution when it doesn't have a program to offer its own training. This can be a way for a school that has lost specialists, or never had specialists in a particular area, to rebuild or establish a specialty area, several university program directors said.

In the case of industry, sponsoring companies typically agree to cover salary and benefits — as set by the university — and other costs associated with resident training, such as office space, phone lines, continuing education and board examination fees, and extra equipment like an ultrasound workstation. And maybe more.

Thrive Pet Healthcare has expanded that scope, for example, with Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, where it sponsors three residents. Dr. Bob Murtaugh, chief professional relations officer for Thrive, said as part of its most recent sponsorship agreement, the company raised salaries by $5,000 for all 22 WSU residents starting this year, for three years. He said it is also providing a dermatology rotation to WSU veterinary students at Thrive locations in Spokane, Washington, and Salt Lake City because the school does not have a dermatologist on faculty.

Incentive packages for residencies seem likely to grow. Stern described sponsorships as a negotiation, and universities have leverage, at least for now. "It's a seller's market," he said.

Universities have to balance these remunerative benefits with their mission, according to Dr. Andrew Mackin, head of the department of clinical sciences at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. The school began taking industry-sponsored residents a few years ago.

“In reality, we all have a certain number of residents that's right for our program,” Mackin said. “We have the right number for teaching students, we have the right number for seeing cases, and we have the right number for us to be able to train them effectively. And if we exceed that number, we either are not helping ourselves, or we're not helping [the residents].”

In general, veterinarians apply to and are selected for sponsored and unsponsored residencies in the same way, through a matching program, colloquially called The Match, administered by the American Association of Veterinary Clinicians. Sponsored residencies are identified as such in the program descriptions, so applicants apply with full knowledge of the terms. Although sponsors talk to applicants and might also rank them, universities usually make the selection.

A subset of sponsored residencies happen outside The Match. Some are competitive; others are created for a particular veterinarian. For example, a hospital struggling to hire a specialist on the open market might seek to sponsor a residency for a promising intern. In this case, the practice and aspiring specialist know what they are getting into.

To some educators who spoke to VIN News, these customized cases raise questions of fairness. "Generally, it's best to go through The Match and compete with everybody else," said Dr. William Thomas, who trains neurologists at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.

Servitude, or opportunity?

Mississippi State's Mackin thinks the perception that sponsored residents are headed for some sort of dismal bondage is misinformed.

“It's more of a theoretical concern rather than a real concern,” he said. "No one wants to fund a three-year residency to get a three-year specialist in their practice and then lose them. They want to keep you, so they're going to bend over backward to give you really good employment for three years. So you want to stay."

Mackin and others point out that agreements with large companies often come with a wealth of options on where to live and practice. They also customarily include buyout clauses, whereby the specialist can end their commitment by paying back the cost of the residency. That exit can run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which may seem prohibitive. However, in today's market, these escape ramps might not be as onerous as they once seemed.

Several veterinarians said practices hungry for boarded specialists would probably be willing to buy out a contract to gain a coveted employee.

"[A]ny number of employers might say, 'I'm happy to pay the $300,000,' " said Dr. Linda Fineman, CEO of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, which certifies six specialties.

UC Davis' Stern said demand is so intense right now that an individual might find it worthwhile to obtain a sponsored residency and buy out their own contract.

"If you think about it, there are plenty of people out there in the world who would pay to do a residency. And depending on the specialty, it would be a pretty good financial investment," he said, referring to the higher salaries commanded by some specialists.

Universities sponsor, too

VIRMP_screenshot

Screenshot

While there are plenty of veterinarians who aspire to specialize, training slots, known as residencies, are limited. Last year, there were 1,314 applications for 503 resident positions offered through the Veterinary Internship and Residency Matching Program, which facilitates the majority of trainee placements. While the number of residencies has risen in the past decade, the number of veterinarians seeking residencies has grown at about the same pace. Ten years ago, there were 829 applications for 267 positions.

Click here for a larger view

Dr. Taya Marquardt knows first-hand the pain of too few residency opportunities.

Marquardt graduated from Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine in 2008 and followed her schooling with a small animal rotating internship in private practice in North Carolina. A small animal rotating internship provides broad clinical experience through a variety of areas, usually emergency and critical care, internal medicine, primary care and surgery, plus electives such as anesthesia, ophthalmology, dermatology and cardiology.

Marquardt hoped to specialize in oncology but failed to land a residency on her first try in 2009. "That was where I really got into what I think a lot of potential specialty candidates [experience], which is the mismatch between the number of candidates and the number of open [residency] positions," she said.

Some years are harder than others. This year, 62 veterinarians vied for 23 oncology resident positions through The Match. In 2018, 78 contended for 21 spots, making it the most competitive year since 2014, the first year for which this data is available.

"So I did what pretty much everybody does for their plan B, which is a specialty internship," she said. She did an oncology internship at Mississippi State University School of Veterinary Medicine.

Fineman at ACVIM confirmed that Marquardt's experience is typical of veterinarians wishing to become oncologists. "It is now a growing trend that people do a general rotating internship, and then they follow that with an oncology specialty internship, and often now, they're following it with a clinical-trials internship in order to try to compete for an oncology residency effectively."

In other words, aspiring oncologists often do three internships, positions that pay much less than general practice. Taking that path in pursuit of a residency can exacerbate young veterinarians' financial struggles.

When Marquardt finished her oncology internship at Mississippi State, the school's only faculty oncologist left for private practice. The school arranged for Marquardt to stay as a clinical instructor for a year. The following year, she again failed to match with a residency, so she went into general private practice in Florida.

"I still wanted to be an oncologist, still was applying for residencies but not matching for them," she said. "I was starting to wonder if this was ever really going to happen, and if maybe I needed to regroup on career goals and be an internist who just really, really likes cancer cases."

In the meantime, after Mississippi State's effort to hire an oncologist to replace Marquardt's mentor wasn't successful, the university asked her if she'd consider doing a residency sponsored by Mississippi at a school with an oncology residency, and return as faculty for three years.

"It took me about a hot second to say yes," she said.

Marquardt trained at Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine from 2013 to 2016. Then she returned to Mississippi, where she had a three-year obligation. Now wrapping up her sixth year, she has no plans to leave. "It has worked out beautifully," Marquardt said.

Beyond sponsorship

Sponsorship isn't the only strategy for companies aiming to grow specialty staff. Some offer their own residency programs — more all the time. The number of private practice-based residencies listed in The Match increased from 58 in 2020 to 94 in 2022.

Like sponsored training, many of the private-practice residencies come with commitments to work at the practice when the residency is completed. There are exceptions. Nonprofits Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston and the Animal Medical Center in New York City, for example, have been for decades training residents with no post-training obligations.

MedVet began training surgeons 20 years ago at its first location in Columbus, Ohio, and soon after added internal medicine, cardiology and ophthalmology residency programs.

Initially, there was no obligation to work for the company after completing training, according to Dr. Jon Fletcher, MedVet director of postgraduate medical education and clinical studies. "The reality is, when these programs were started, they were started for the sake of training veterinary specialists and growing the profession and giving back," he said. "When it came to even the opportunity for these early residents to stay on, it probably didn't exist most years."

As MedVet grew, there were more long-term employment opportunities for residents, and it began to train more specialists for its own hospitals. Today, the company offers residencies in eight specialties and plans to increase the number of residencies and specialty areas.

"We need to train more specialists, and we need to do that as a partnership between academia and private specialty practice," Fletcher said. "I mean, there may be some things that universities inherently do a bit better, but we are very capable of training high-quality specialists in private practice."

Launching new training programs is not an easy endeavor, Fletcher said. "You can't just flip a switch. It can be challenging."

The challenge stems in part from the criteria practices must meet to qualify as training sites for would-be specialists. The organizations that certify diplomates set myriad, stringent requirements including a minimum number and array of boarded specialists at training sites, support facilities, equipment, caseloads, hours of didactic training and more.

“When we started as a specialty college, we were aiming to train academic veterinarians to become specialists and researchers,” said Fineman about ACVIM. “Now, we've got this huge private practice sector that has maybe a different set of requirements than what was envisioned 40 or 50 years ago when specialty medicine started.”

Thrive's Murtaugh says criteria forged in the halls of academe leaves many private practice and university training opportunities "hamstrung.”

One example he'd like to see modified is a requirement that a given training site employ at least two boarded specialists in the resident's specialty. Murtaugh maintains that specialists at multiple sites in the same company or shared between a private sector and university partnership should count toward the total.

Despite its issue with some rules, Thrive has been able to offer its own residencies. The company currently has 30 to 40 trainees in dermatology, ophthalmology, neurology, and emergency and critical care. This is in addition to amping up sponsorships. Murtaugh calls the multipronged approach a "major endeavor" for the company.

"We should be looking at ways to meet the demand while still maintaining the standards," he said.

Fineman feels the heat, and she understands it.

"There is broad pressure affecting all associations that certify specialists. It's market pressure, basically," she said. "There is significant demand, and there are not enough people to fill the demand, and so if you're any of the potential employers of the people that we train and certify … [you] are anxious for there to be more opportunities."

She described this issue as a “big area of conversation” at the ACVIM and among association executives. She said they are considering: “How might we help our boards consider adapting to meet the market? And, most importantly, how do we do that and maintain the quality of programs?”

Offering her personal opinion, she added, “There are strengths associated with private practice residencies and strengths associated with academic residences. There's great opportunity for us to work collaboratively to try to harness the best out of both settings."