University of Melbourne plan stirs debate on importance of on-campus clinical training

!This story has an important update

Protest

VIN News Service photo

Dozens of protesters, some brandishing placards, others holding dogs, turned out in blustery conditions on Monday to oppose the planned closure of the University of Melbourne veterinary teaching hospital.

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

A plan by one of Australia's largest universities to close its veterinary teaching hospital is stoking debate in the profession about the value of campus facilities that offer students vital hands-on experience but are costly to run.

Citing financial pressures, the University of Melbourne this month announced a plan to close its veterinary school's teaching hospital, known as U-Vet, that would result in about 80 employee layoffs.

The plan, endorsed by university management but not final, is opposed by the Australian Veterinary Association, which contends it will lower educational standards and fears it could foreshadow hospital closures at other schools.

The move also has met opposition from some of the school's 480 students, who staged a protest on Monday outside U-Vet, located in the Melbourne suburb of Werribee, that was attended by at least 60 students, staff and pet owners — around a dozen with dogs in tow.

"One of the reasons I chose this school specifically was because it had a teaching hospital," Sofia Ballesteros, a third-year international student from Colorado, told the VIN News Service on an uncharacteristically cold and blustery spring day. "I thought the hospital, which the university really advertised as this amazing feature of the program, would ensure that students were getting the most out of their education."

Some staff members in attendance, speaking to VIN News on condition of anonymity, questioned whether the entire veterinary school's future is under a cloud. Others expressed disappointment that they soon may have to find new jobs.

"I feel pretty sad," said Dr. Astrid Oscos Snowball, a clinical pathologist at the teaching hospital. "I moved my whole family from Canada to work here." Snowball, who relocated to Australia in 2018, said she's recently had three job offers in the United States but would like to stay in Australia.

The university proposes to adopt a so-called distributed teaching model whereby students attain practical experience offsite at private hospitals that partner with the university. "This is a model used by many other veterinary schools around the world and is a framework for delivery of clinical teaching recognized by the accrediting bodies," the university vice chancellor, Duncan Maskell, said in a letter to staff.

Most of the world's top-ranked veterinary schools have teaching hospitals, though possessing one isn't mandatory to gain accreditation from official bodies such as the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education. The University of Calgary in Canada and the University of Nottingham in England, for instance, are AVMA-accredited but do not have teaching hospitals.

Still, should the University of Melbourne proceed with the plan, it would become the only one of Australia's seven veterinary schools without a teaching hospital.

The planned hospital closure is part of a broader restructuring at the University of Melbourne, which also said this month that its schools of veterinary medicine and agriculture would be absorbed into its science faculty.

The shakeup has included the departure of the veterinary school dean, Dr. John Fazakerley, who left on Nov. 11. The school did not publicly divulge the reason.

In a letter to staff, Fazakerley suggested he'd been forced out, saying he was disappointed to be standing down "with only a few days' notice, particularly as we approach the graduation of our students and our annual end-of-year celebrations."

Moira O'Bryan, dean of the science faculty and a human reproductive biologist, has been appointed acting dean of the veterinary school. A veterinarian, Dr. Josh Slater, has been appointed as the school's acting head. AVMA COE accreditation requirements stipulate that a veterinary school's "chief executive officer/dean" be a veterinarian.

Slater, in a letter to hospital clients, said the university is seeking staff and stakeholder input before making a final decision on the hospital's future. Among the stakeholders is the AVA, whose president, Dr. Bronwyn Orr, said the association is attempting to persuade the university to keep the hospital open.

"We think it's really important that our universities have nation- or world-leading veterinary teaching hospitals," Orr said in an interview. "There's so much that can only be done in that sort of environment and culture that I think would be quite difficult to achieve in the private sector."

Costs at teaching hospital 'almost doubled'

Teaching hospitals at educational institutions strive to offer students a gamut of hands-on clinical experiences, from basic procedures to specialist care in a variety of disciplines, whether for small, large or exotic animals. They also offer veterinary services to local communities. Private clinics may refer patients to teaching hospitals for specialist care.

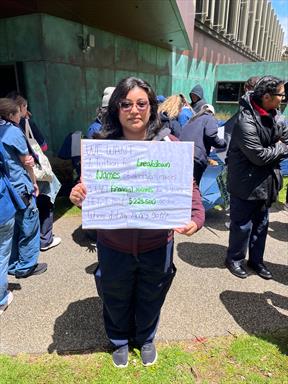

Sofia

VIN News Service photo

Among the protesters, Sofia Ballesteros, a third-year DVM student from Colorado, held a placard listing some of the students' demands, including a breakdown of how their tuition fees are spent.

Teaching hospitals are designed first and foremost as educational facilities, not as a means of raising revenue from their animal-owner clients. AVMA accreditation requirements, for instance, stress that a teaching hospital's function as an instructional resource "must take priority" over the financial self-sufficiency of any clinical services it provides to the public.

In his letter to staff, Vice Chancellor Maskell cited a combination of falling revenue and rising costs, which "almost doubled" over "several years," for the university's plan to close the hospital. Challenges included attracting and retaining talent at a time when veterinary professionals are in short supply worldwide, Maskell said.

The university declined to provide VIN News with further detail on its financials, including what caused its revenue to fall and how much money it would save by adopting a distributed teaching model. U-Vet is located about 20 miles from central Melbourne and positioned next to a major highway. An online petition, which asserts that the hospital's closure would be a "huge loss" for pet owners in western Melbourne, has attracted more than 8,000 signatures.

Some students are demanding the university open its financial books for the past five years to show how tuition fees are spent. International students in the school's four-year graduate DVM program, who comprise about 40% of the school's student body, pay a total of A$333,362 (US$220,624), according to an "indicative" course fee cited on the university's website. Australian citizens pay A$266,331 (US$176,262).

Hailey Lee, a third-year international student from South Korea, said she was shocked by the school's plan and now doubts that she chose the right place to study. "If they close the teaching hospital now, the students here will receive different levels of education, which is not fair," Lee said at Monday's protest. At the least, the students want the university to continue operating the hospital while putting it up for sale to the private sector so existing staff can keep their jobs. The university said it is "exploring the potential for a third-party commercial veterinary business to operate from the Werribee hospital facility."

Accreditation concerns rise

Tensions are growing at a time when Australia's universities, partly reliant on income from full fee-paying foreign students, continue to recover from border closures prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Australia in March 2020 closed its international borders and didn't reopen until February, almost two years later.

Statue

VIN News Service photo

A statue of a veterinarian holding a newborn calf and watched by an Australian kelpie was installed in 2010 to commemorate the centenary of the University of Melbourne's faculty of veterinary science. Entitled "New Life," the statue stands outside the U-Vet teaching hospital. The hospital's future is now uncertain.

The University of Melbourne's veterinary school already has fallen short of some AVMA accreditation requirements. In September, the American association said the school was on "continued probationary accreditation," with minor deficiencies in physical facilities, clinical resources and faculty; and a major deficiency in its curriculum. The accreditor did not elaborate on the deficiencies. The AVMA COE is scheduled to perform a "verification site visit" to the school next summer.

Ballesteros, the student from Colorado, is concerned that closing the teaching hospital might affect the school's reputation overseas, including in the U.S. "I believe the way this all has been handled is very disheartening, and I'm very worried about the accreditation status of the university going forward," she said.

The university told VIN News in an email: "We do not expect the proposal and changes will impact accreditation. We are in conversation with all relevant accreditation bodies to work through their feedback in combination with our staff, students and community in relation to the proposal."

Employees at the school have been feeling the strain for years, according to Annette Herrera, a branch secretary at the National Tertiary Education Union, which represents hospital staff. "There's been multiple rounds of job cuts," Herrera said in an interview. "There was a round last year; there was one two years before that. Services already have been cut, including emergency services."

Herrera said she believes public institutions have a greater responsibility to serve local communities than private businesses. "The difference between a private hospital versus a university is that a university is supposed to be for the public good, and this one has done a lot of good for people in the west of Melbourne," she said.

At least one other hospital at an Australian veterinary school has shown signs of stress. The veterinary teaching hospital at Murdoch University, located in the state of Western Australia, in May became the subject of a workplace safety probe amid union claims that staff were being overworked and animals weren't being cared for properly. Murdoch University denied the allegations but has acknowledged that hospitals everywhere are grappling with staffing pressures triggered by a pandemic pet boom and difficulties retaining talent.

Pros and cons of the distributed model

Final-year students

VIN News Service photo

Final-year DVM students Sita Jhaveri and Tara Jadwani-Bungar said they discovered on the day of their final exams that the teaching hospital may close.

Switching to a distributed model, its proponents claim, offers universities a win-win solution — they can save money while still offering students high-quality practical experience at private hospitals that meet standards set and monitored by the university.

Moreover, keeping students inside a university bubble often is cited as a reason that the profession is struggling to retain practitioners, who may enter the workforce with unrealistic expectations of what clients are willing to pay for and, consequently, how often veterinarians will perform advanced medical procedures.

The University of Melbourne said it would be able to "build on" existing teaching arrangements with three private hospitals, located in Essendon Fields, Moorabbin and Mornington. The hospitals are about 21, 32 and 61 miles from U-Vet, respectively.

Most schools with teaching hospitals offer students externships, too. "Real-world experience is important, but I think it comes down to balance," Orr of the AVA said. "There's a lot of things that teaching hospitals provide. Obviously, employment for specialists is one thing, particularly specialists that might not be hugely income-generating but still are very important to the veterinary landscape."

Private businesses, she added, don't necessarily have the right culture to be the sole providers of hands-on training. "In many ways, for-profit hospitals have different drivers," she said. "Education's not necessarily their number-one kind of motivation, and therefore, students might not get that full experience."

Orr's views were shared by several students at Monday's protest. Erica Martin, an ICU nurse at U-Vet and first-year DVM student at the university, said she found teaching standards "vastly, vastly different" at private clinics. "Where you're in a facility that's not really set up for teaching, often you'll find that students are in the way," she said. "And it's much less a case of hands-on learning, and much more 'stand back and observe.' "

Final-year DVM students discovered on the day of their last exam that the teaching hospital might be closing, according to Sita Jhaveri and Tara Jadwani-Bungar. Although neither will be directly affected by a closure, they feel for the school's ongoing students. Jadwani-Bungar noted that some, like her, had moved to Werribee to live.

"Private clinics don't have the resources to give students 40 minutes per client; they don't have the resources to spend five catheters per pet to let us try and try again," Jhaveri said.

The university appears unfazed, maintaining that it can offer top-quality clinical experience through a distributed model. "We have strong demand for the program year after year, and don't anticipate any change in student numbers as a result of change plans," it told VIN News.

On the cost burden of running a teaching hospital, the AVA's Orr accepts that many Australian universities are facing financial challenges, especially at their veterinary schools. "I think that something has got to change — and an ideal solution would be increased federal government funding for veterinary places," she said. "Hopefully, this is a bit of a wake-up call for the entire profession to realize that we need to be more proactive in this space to support our veterinary schools. Otherwise, who knows what path we're going to go down."

Update: On Dec. 14, the university said it would cease operating the teaching hospital as of Dec. 24. It also announced that it has agreed to lease the facility to Greencross, an Australian corporate consolidator that owns more than 160 veterinary practices. Greencross will operate a general practice clinic, together with a 24‐hour specialist and emergency hospital, at the facility from "early 2023" and employ "a number" of university staff to provide clinical teaching and placement opportunities for DVM students, the university said.