Cattle loss

Photo by Dr. Kylie Stewart-Moore

Authorities estimate that hundred of thousands of cattle perished in record-breaking floods in North Queensland, Australia. Dr. Kylie Stewart-Moore tried to save the cattle on her ranch in Hughenden, a town in the province. Despite her efforts, many perished.

As waters crested the banks of the Flinders River in early February, veterinarian and cattle producer Dr. Kylie Stewart-Moore set out to save animals on her 120-acre ranch in Hughenden, Queensland.

Despite her efforts, she lost many. So did other area ranchers.

A year's worth of rain had inundated northwest Australia during the first week of February, causing the normally narrow Flinders River to swell to unprecedented levels. Some of the area's cattle, sheep and wildlife were swept away and drowned. Others succumbed to freezing winds and died of hypothermia.

"All the while, it kept raining," Moore said, "and we couldn't access these animals to help."

Weather-related devastation isn't unique to Queensland, of course. Halfway around the world, residents of Northern California are similarly distressed this week by heavy rain and flooding. Cities turned to islands as the Russian River rose 15 feet above flood stage. California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared an emergency in five counties. The California Veterinary Medical Association said Thursday that it did not know yet if area veterinarians were affected.

Globally, natural disaster and severe weather occurrences are on the rise, according to the research portal Statista. Catastrophic natural events have tested the resilience of vast populations, veterinary professionals and other first responders among them. While disaster prediction is an evolving and inexact science, the National Center for Atmospheric Research forecasts an uptick in the frequency and voracity of fires, hurricanes and floods. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration states the same for extreme weather.

Dr. Barry Kellogg's most memorable brush with disaster followed a manmade catastrophe. As a first-responder, he was called to Ground Zero following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Since then, he's responded to multiple disasters and has developed protocols for responders and veterinarians.

Most important, he said, is to prepare and plan locally. "If we have learned anything, it is that successful disaster response depends entirely on the local community's preparedness and local resources," Kellogg said. "Do not depend on federal support or response. It does not work."

Kellogg advocates for planning ahead, suggesting that veterinarians map their evacuation routes, identify food and water sources, stash medical supplies and have local emergency management contacts on hand. Veterinary hospitals should coordinate with other practices in the area to devise emergency plans and put them in writing. "... If it isn't written down, it doesn't exist," Kellogg said.

"What you do to plan for the unexpected can save lives," he added. "But the mental toll a disaster can take, that can be much harder to navigate."

In Queensland, Moore said she's devastated. "... [O]ur cattle are so important to us and we have lost more than a thousand, and we are still dealing with a lot in the recovery here," she wrote in a message to the VIN News Service.

The province is home to more than 11 million cattle, according to Australian government statistics. Authorities estimate that flood waters killed more than 300,000 head of cattle. Adding to the devastation are cases of melioidosis, a zoonotic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei, which is picked up from clay soil. The disease has sickened 13 area residents and one woman has died, public health officials reported in a Facebook post dated Feb. 18.

So far, Moore hasn't encountered melioidosis on her ranch. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, B. pseudomallei is seen most often in pigs, goats and sheep, and occurs less often in cattle and horses. She treated surviving cattle with a mixture of calcium, phosphorous, magnesium and glucose. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatories were administered to cattle with signs of pneumonia, rain scald or cellulitis, she said.

Moore recently turned to Facebook to thank local pilots who performed aerial searches, and colleagues who trudged through water and black sludge to help feed, treat or euthanize animals.

"Although we are devastated for the animals we have lost, we still have a good proportion of our cattle spread out, eating and enjoying the sun," she wrote on Feb. 10. "I can't fathom the feeling of losing every animal in your care, and I'm so sorry that this has happened to so many."

Alaska earthquake

Photo courtesy of Dr. Lorelei Hass

A 7.0 magnitude earthquake shook the practice where Dr. Lorelei Hass works in Anchorage, Alaska. Aftershocks continue to rock the region, months after the earthquake in November.

Shaking in Alaska

It was 8:30 on a Friday morning when the building began to shake and rumble. Dr. Lorelei Hass and her colleagues grabbed coats and ran to a doorway as the temblor intensified.

"We threw them over ourselves in case glass started flying," she said.

Ravenwood Veterinary Clinic was bearing the full force of a magnitude 7.0 earthquake that rocked Anchorage, Alaska, on Nov. 30. Books flew off shelves, walls cracked and windows broke.

"We were just into our workday and lucky that our surgery doctor for the day hadn't started patients under anesthesia," Hass said. "No employees got hurt, and no pets got hurt. We were lucky."

Others are less fortunate. According to the insurance consulting firm Aon Corp., the world was besieged by 394 natural catastrophes in 2018, most of which were weather-related events. Economic costs associated with the disasters totaled $225 billion, with insurance covering $90 billion of the total, the firm reported.

The first $1 billion crisis of 2019 struck in January in Argentina, where severe flooding caused death and destruction in three provinces.

In response, the veterinary council in Chaco opened its doors to the region's needy animals, setting up a place for private practitioners to administer vaccines and parasiticides to area pets. "… We thank the great veterinary family that day by day collaborates in these extremely difficult moments," reads a post on the council's Facebook page.

Crosses

Photo by Dr. Valerie Caruso

The Camp Fire claimed the lives of 85 people in Paradise, California.

Caught by surprise

After practicing for nearly 30 years in the town of Paradise, California, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, Dr. Valerie Caruso was familiar with the perennial threat of wildfire. But she said there's not much you can do to mentally prepare for flames ripping through and leveling your town in a matter of hours, which is what happened on the morning of Nov. 8.

Although the blaze initially wasn't near her practice, Companions Animal Hospital, the winds were kicking up, so Caruso instinctively turned away patients, fearing she'd lose power eventually.

Her hunch proved prophetic. Within an hour, Caruso was evacuating to her home in nearby Chico, headed down the hillside, followed by neighbors, friends and staff. With fire consuming Paradise, the town and its windy roads become a deathtrap.

By noon, Paradise was decimated. Eight-six people perished, making the Camp Fire the deadliest in California history — a macabre feat, considering state's unprecedented fire season.

Some of the victims were Caruso's clients. Her staff all escaped, but barely. The random nature of the fire left Caruso's practice untouched but torched everything else in the vicinity.

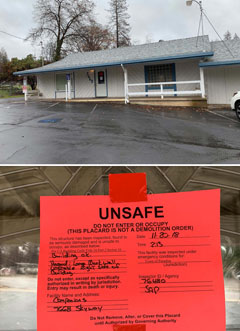

Companions Animal Hospital

Photo by Dr. Valerie Caruso

Companions Animal Hospital didn't burn but the building remains uninhabitable months after the fire, according to owner Dr. Valerie Caruso.

Caruso won't return to work in Paradise — her clinic building has been deemed unsafe to occupy because the burned-out remnants of a neighboring structure could topple hers. The building smells of smoke and needs to be decontaminated. More importantly, there is no infrastructure in the town; the utilities aren't working. The public water system is contaminated by benzene, a carcinogen.

What's more, there are no residents, meaning no clients to serve, nor employees to work.

"I've only met one client planning on rebuilding in Paradise. All others say, 'No way,' including my employees and friends," she said. "… We're all still in shock, trying to move forward, but it's hard. It's so depressing."

Chico, at the edge of the Sacramento Valley, is bulging with thousands of the displaced. Caruso has friends sharing her small home. She's considered renovating her garage to better accommodate them.

"Everyone's just trying to get by," she said. "It's a mess."

But the fog seems to be lifting. Earlier this month, Caruso's business interruption-insurance came through. "They finally paid for the past two months," she said, elated. And Caruso is still doing work she enjoys — helping animals and clients — even if it's not in her own practice.

There's been an uptick in activity on the Companions Animal Hospital Facebook page. The exchanges feature status updates and other announcements. Caruso recently posted: "There is a left-behind pet duck in Paradise. His name is Carl. Can anyone give him a forever home?"

Others are looking for care: "I need an appointment. Please call me as my baby has another ear ache. … I'm also in Chico now!"

Caruso has announced that she, too, will make Chico her professional home. Construction has begun on a new practice. If all goes as planned, she could open before spring.

"Are you not coming back to the Paradise building?" a client recently asked on Facebook.

"No plans at this time," Caruso replied, acknowledging the loss of "90 percent" of her clients.

Dr. Belen Acevedo

Photo courtesy of Dr. Belen Acevedo

Dr. Belen Acevedo joined other veterinarians who volunteered to care of animals after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017.

Victim turned first-responder

Dr. Belen Acevedo knows what it means to recover from a life-changing event. The 38-year-old veterinarian was at her parents' home in Humacao, Puerto Rico, when Hurricane Maria made landfall on Sept. 20, 2017.

"We didn't know what was going to happen," she said. "We stayed there and thought we'd have everything under control."

But they didn't. The Category 4 hurricane decimated Humacao, on Puerto Rico's southeastern coast, along with most of the island. Three-and-a-half million residents were plunged into the longest blackout in U.S. history. Many were homeless. Electricity was not fully restored until nearly a year later. By then, many had left the island to relocate elsewhere.

Before Maria, Acevedo was doing relief work for Banfield Pet Hospital and saving money to open her own practice. After Maria, she made herself useful, joining Veterinarians for Puerto Rico, a nonprofit established by practitioners on the island and across the U.S. mainland.

"People were looking to buy food, for themselves and their animals. No one was taking care of the trash. There were leptospirosis outbreaks. Animals were sick," she said.

Dog amid trash

Photo courtesy of Dr. Belen Acevedo

Trash accumulation, debris and a lack of drinking water resulted in an outbreak of leptospirosis.

Donations to Veterinarians for Puerto Rico allowed Acevedo and others to vaccinate and care for animals. "We went to the most affected areas," she said.

Today, most things have returned to normal, but animals still roam free, abandoned by owners who moved away. Acevedo volunteers to spay and neuter them, but that doesn't solve the problem of their homelessness.

In May, she opened her own practice in Caguas. Asked if she'll evacuate or hunker down when the next massive storm threatens Puerto Rico, Acevedo took time to consider the question before answering:

"I'd probably stay again. We're used to hurricanes. I'll get more food and dog food, probably enough to provide for a month at least, and medication. And health certificates — we had no computers to get the forms, so I'll make paper copies next time.

"Now I'd have everything ready," she said.

Impervious to ruin

Insurance money and personal resolve couldn't save Dr. Gary Levy's practice from the wrecking ball after Hurricane Katrina wiped out much of New Orleans in late August 2005. The hurricane's 28-foot storm surge filled the bowl-shaped city, causing billions of dollars in damages and killing more than 1,000 residents.

His message for facing disaster: "Don't jump off a bridge. There is life after this. Be hopeful and call on the resources you can."

But it wasn't easy. Levy said it took all he had to rebuild Lakeview Veterinary Hospital, a five-doctor practice. During the months post-Katrina, Levy teamed with Dr. Patrick McSweeney, a friend and fellow practitioner in the area, to care for sick animals. McSweeney had lost his home but his practice was still standing.

Fueled by friendship, military-grade Meal, Ready-to-Eat packages and adrenaline, the duo went to work. What they saw was overwhelming and depressing. The streets were desolate and in ruin, piled stories high with debris. Mold and mildew covered everything that stood still. And few clients remained in the area.

"The joke down here was that we needed Prozac in the water supply," Levy recalled. "At so many levels, you face depression. But it was the little things, like those clients who came from 40 miles away when they found we were back open.

"Life goes on," he added.

Nowadays, things have changed for the better. Levy has rebuilt, enlarging his practice's footprint to 4,000 square feet. He's now five years into a new building, and loves it.

The evolution of Lakeview Veterinary Hospital — and the neighborhood around it — took about 10 years, Levy said. While a significant elderly population lived in homes near the practice before the hurricane, many did not return. The ruins and empty lots were snapped up by young aspiring homeowners, spurring a resurgence.

"There was a rush of 30-year-olds with money and heart," Levy said. "Many of them brought up double lots, built larger houses and made this neighborhood their home."

As for the practice, "pre-Katrina, our numbers were about 3,500 dogs and 1,700 cats a year. We made it back to those numbers in about 2015," he said.

Levy advises anyone who owns a practice to make sure they carry enough insurance coverage and understand their policies: "Wind versus water damages … what does that really mean? Or business interruption insurance … does that really matter? You need to know the ins and outs of that," he said.

Asked whether he'd stick out another Katrina-like storm, Levy hedged.

"If anything like this happens again, last one turns the lights out," he said. "I'm not going to do this again."