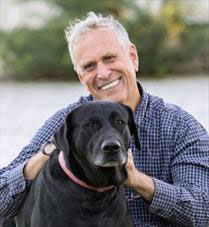

Photo by Mark Meranta

Dr. Ronald Hines wants the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether his right to free speech is a reasonable claim in a lawsuit against state regulators who forced him to stop evaluating animals and giving medical advice via the Internet. The Texas veterinarian is pictured with his dog, Max.

Dr. Ronald Hines is taking his free speech case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Texas veterinarian, who spent years providing low-cost medical advice to pet owners over the Internet, believes the First Amendment should protect his telemedicine practice.

Hines and his representation, the public-interest law firm Institute for Justice, want the high court to overturn a recent appellate ruling that upholds the Texas Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners' right to regulate its professionals by mandating that a physical exam be required before offering care. Lawyers for Hines argue that the board's "obsolete regulatory barriers" encroach upon his right to give advice about medical cases.

"It just seemed counterintuitive and quite foolish," Hines said. "Your hairdresser can discuss your pet’s health issues with you, but I can’t."

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals' decision is just one element of Hines v. Texas Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners, which has yet to be adjudicated by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas. Last spring, lawyers for the state filed a motion for interlocutory appeal, a civil procedure that asks an appeals court to rule on elements of a lawsuit still active at the trial court level.

At question was whether Hines' free speech argument was a reasonable claim.

The Fifth Circuit doesn't think so, according to its ruling filed March 27. Circuit Judge Patrick E. Higginbotham wrote in his decision that state regulators weren't stifling Hines' speech; they were upholding standards for licensed practitioners.

"Here, the requirement that veterinary care be provided only after the veterinarian has seen the animal is, at a minimum, rational: It is reasonable to conclude that the quality of care will be higher, and the risk of misdiagnosis and improper treatment lower, if the veterinarian physically examined the animal in question before treating it," he said.

Whether the nation's highest court will hear Hines' appeal is uncertain; justices considered roughly one percent of more than 7,300 filings in 2013 — a proportion that varies little on an annual basis.

Either way, the question persists as to whether veterinarians should be allowed to provide advice for animals they've never physically examined. To Hines' way of thinking, it's time that the veterinary profession advances by embracing telemedicine, given that electronic communications are playing a growing role in human health care.

That's not to say virtual medicine is without controversy. As regulators examine the role of electronic communications in veterinary care, their counterparts in human medicine are doing the same. The Texas Medical Board reportedly is in a legal battle with doctors who consult with patients by video. Telemedicine advocates argue that the field is evolving beyond brick-and-mortar practices to incorporate technology that benefits patients.

The American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Medical Ethics is ambiguous as to whether a patient-physician relationship can be formed by telemedicine alone. Additional guidance from the group's Council on Medical Services states that "a valid patient-physician relationship must be established through a minimum face-to-face examination" that could occur in person or through real-time audio and video technology.

Whether state regulators adopt AMA guidance, and to what degree, is up to them. That autonomy that has led to hodgepodge of state laws governing the use of telemedicine. The same is true on the veterinary side, though the American Veterinary Medical Association appears to be more conservative in its recommendations. The AVMA model practice act specifies that a physical examination is needed to establish a veterinary-client-patient relationship (VCPR), with few exceptions.

Even so, most state veterinary boards do not have language that encompasses aspects of telemedicine in their VCPR requirements, said Adrian Hochstadt, an attorney and assistant director of AVMA State Legislative and Regulatory Affairs.

"What's referenced in the provision in Texas mirrors the AVMA model code that says you cannot establish a VCPR by telephone or other electronic means," he said. "If states would employ that specific language, they'd be in a much better position to face challenges like this."

Those states that do not have regulations pertaining to online advice are more susceptible to legal challenges, he said. "You still need a VCPR, but can you create one on the Internet? In my opinion, all of this is somewhat up in the air. It doesn't mean that in those states with a general VCPR requirement you can do it, it's just not as clear."

Veterinary boards in a handful of states, including Texas, Iowa, Utah, Illinois and Mississippi, have rules that echo the AVMA's model act by forbidding the establishment of a VCPR solely through electronic means; the veterinarian must examine the patient or conduct timely visits to the premises where the animal is kept.

"The issue is not whether telemedicine can be used for ongoing treatment," said Raphael Moore, general counsel for the Veterinary Information Network (VIN), an online community for the profession. "The issue is whether telemedicine can be used to establish a relationship when that is being outlawed in more and more states."

One such attempt is in California, where veterinary regulators are pushing a proposed addendum to the California Veterinary Medicine Practice Act that reads: "No person may practice veterinary medicine in the state except within the context of a veterinarian-client-patient relationship. A veterinarian-client-patient relationship cannot be established solely by telephonic or electronic means."

Such a change must be approved by the California Legislature, which can be an arduous and unpredictable undertaking.

Taking a case to the U.S. Supreme Court also isn't easy, Hines said. At age 72, Hines has been retired from traditional practice for more than a decade, owing his exit to a spinal injury. He began consulting with pet owners via his website, 2ndchance.info, as a way to stay connected and help patients. In 2013, Texas regulators forced him to shut down. He had been offering medical advice for a $58 flat fee. Sometimes he didn't charge anything.

Hines, who spent much of his career treating zoo animals, told the VIN News Service last year that he started the website to help animals and stay connected. "People talked to me, and I enjoyed that. I felt like I was doing some good, like I was accomplishing something," he said. “They don’t write to me when they have a ear infection or broken toenail. It’s always a mystery disease that comes and goes, a failing heart, a ton of medications. I find that intellectually challenging."

Hines said he encouraged owners to seek a physical when needed and never prescribed medication. His service netted roughly $1,800 a year.

The Fifth Circuit did not take that into consideration when finding Hines' advice to be outside the First Amendment's parameters. "What is clear — and undisputed — is that Hines' remotely provided services constituted the practice of veterinary medicine," the court ruling states. "This was a problem. Under Texas law, '[a] person may not practice veterinary medicine unless a veterinarian-client-patient relationship exists.'"

Dr. William Folger, a Houston-based feline specialist and president of the Society for Veterinary Medical Ethics, agrees with the Fifth Circuit's decision. He also supports the regulatory board's efforts to stop online practice, pointing out that animals can't talk to their doctors, which adds a layer of difficulty to veterinary telemedicine.

"Our patients cannot speak to us; we cannot have a Skype interview," Folger said. "Someone can Skype me, but they’re just going to sit there at the keyboard. (Animals) can’t answer questions, which makes that kind of interview process a moot point."

Nevertheless, plenty of veterinarians are taking their expertise online. Many offer general wellness and nutrition information but steer clear of diagnosing and recommending treatments.

Institute for Justice attorney Matt Miller, who represents Hines, believes the ultimate outcome of his case will impact professions beyond the scope of veterinary medicine. With regard to free speech, he considers the Fifth Circuit's decision to be troubling.

"The court ruled that the individualized advice of licensed professionals — like veterinarians, doctors or accountants — is either outside the First Amendment entirely or enjoys only the most minimal First Amendment protection," Miller said. "Under this ruling, a veterinarian’s website would be protected by the First Amendment, but the actual words he or she speaks to pet owners would not. That is a dangerous precedent that all professionals should be concerned about."

He added, "... We are hopeful the Supreme Court will correct the error."

VIN News Service journalist Jennifer Fiala contributed to this story.

This story was changed from the original to clarify the quotation by Raphael Moore.