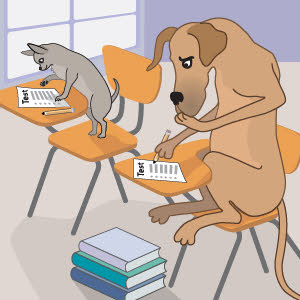

Smart dogs

VIN News Service illustration by Tamara Rees

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Anyone who spends much time looking at scientific studies knows that the titles typically are dry and not eye-catching. So when research comes out in a peer-reviewed journal with the heading "Little brainiacs and big dummies: Are we selecting for stupid, stout, or small dogs?" you pay attention.

The colorfully titled study, published in February in Open Veterinary Journal, looks at the relative brain sizes of big to little dogs, makes a disquieting observation about the weight of dogs today compared with a century ago, and muses on canine intelligence and the essence of "dogness."

It all originated not with a hypothesis but from the quizzical mind of a veterinary data-cruncher who started playing with a pile of measurements he happened to have on the volumes of dog brains.

The measurements had been taken by Drs. Mark Rishniw and Curtis Dewey at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. The numbers were derived from MRIs that Dewey, a neurologist, had done on dogs for other research.

Rishniw is a cardiologist with an aptitude for data analysis and a wide-ranging curiosity. He is also research director at the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession. With the MRI information at hand, Rishniw decided to graph the dogs' brain and body sizes. There's a huge difference in sizes among dogs — it's the greatest difference among species — but he expected that the brain-to-body proportions would be consistent from dog to dog.

They weren't.

What Rishniw and Dewey discovered is that the little dogs had eight times as much brain mass for their body sizes as the big dogs. That led to the provocative question: Are little dogs smarter than big dogs?

The concept that a relatively large brain indicates greater intelligence has long held sway in the public imagination. Elephants are smart, right? And chickens, well, you've probably heard "bird brain" brandished as an insult. Rishniw and Dewey explore whether "encephalization" — the idea that the bigger the brain, the smarter the creature — applies to domestic dogs.

But first, Rishniw dug into the literature and learned that a few scientists before them had compared dog brains and body sizes, and found the same pattern of differing proportions: The little dogs had bigger brains relative to their body mass than the big dogs.

The earlier data was published in 1891 by Charles Richet, a French physiologist who measured canine brains preserved in formalin. Looking at Richet's work, Rishniw discovered another surprise: Dogs 130 years ago had notably heavier brains relative to their bodies than dogs today — on the order of 10 grams more per kilogram of body weight

What? Have modern dogs' brains shrunk?

No, that's where the "stout" in the paper title comes in. Rishniw and Dewey argue that breeders don't select for small brains or even small heads, and that a century or two of selective breeding is not long enough to naturally evolve that much difference.

The "more reasonable biological explanation," they posit, is that dogs today have heavier bodies. To put it bluntly, they are fatter. The researchers write: "[P]lentiful evidence exists that dogs, like people in the United States, are experiencing an increasing prevalence of obesity."

What makes a dog a dog?

Returning to the observation that little dogs have relatively bigger brains than big dogs, let's hear from Rishniw on what it may mean about intelligence and "dogness."

The new and old data alike indicate that dog brains get only so small and only so large. "Forty milliliters is the finite limit of the brain [on the small end], is what I think we ended up calculating. There's [also] an upper limit where you don't need more brain to be a dog," Rishniw says.

Rishniw and Yarra

Photo by Maya Gasuk

Dr. Mark Rishniw's Labrador retriever, Yarra, weighs some 55 to 60 pounds; brain weight unknown. Asked, is she smart? Rishniw paused. "Um, she's very sweet," he replied.

"I came up with the term 'dogness' [to express that] it takes a certain amount of brain in a certain organization and state to be a dog. Otherwise, you're not a dog; you're something else."

Something else? Rishniw explains: "Literally, a Yorkshire terrier is smaller than a cat and about the same size as a ferret, and yet their brain is considerably bigger. So whatever it is that makes them dog might be related to a critical brain mass."

The lower limit on dog brain size can have unsettling implications for the tiniest of the species. Rishniw points out that toy breeds such as Chihuahuas, Yorkies and some brachycephalic (or flat-faced) breeds have domed heads and open fontanelles — spaces in the skull comparable to the "soft spots" in human babies. Fontanelles close as babies grow, but in affected dogs, open fontanelles are permanent, a feature that sometimes has health implications.

"[W]e keep breeding these dogs smaller and smaller, but their brains are going, 'Well, I'm as small as I'm going to be; otherwise, I'm going to be a cat. I can't get myself any smaller,' " Rishniw says, "and you're going to try to build a little cage around that brain now that can't close."

These brains that are too big to fit the skulls of tiny dogs do not confer more smarts to small dogs than their bigger peers, the researchers contend. "No behavioral evidence exists that small breed dogs are more intelligent than large breed dogs," they write. "Indeed, common wisdom suggests the opposite — that small breeds are less 'trainable,' less sociable, and less smart than large breed dogs."

Rishniw says: "There are a bunch of papers that have tried to estimate intelligence in dogs, and they're all over the place. It comes down to, how do you actually measure intelligence? If you use human criteria to measure intelligence in a nonhuman species, is that valid?"

Dogs are bred for appearance and for behavior — not for smarts, Rishniw says.

Not even border collies, the quintessential A students among domestic canines? "Just because a sheepdog can put three sheep into a pen by listening to your whistles standing across the field, does that make it more intelligent than a Chihuahua? No," Rishniw says, "it's been bred for a particular function, but it might not be able to do a whole bunch of other functions.

"Just because a dog can display a particular behavior that we've bred for and selected for and trained it for doesn't mean that it's intelligent," he argues. "Take a bloodhound. Their entire brain is in their nose, so if you want hunting and tracking, there's your intelligence."

As Rishniw sees it, comparing intelligence among dogs or other nonhuman species might not even be appropriate. "Intelligence," he says, "is an extremely anthropomorphic quality."