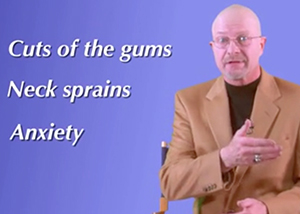

VIN News Service photo

Media personality Dr. Jim Humphries underscores risks of non-anesthesia dental scaling in a video posted by the American Veterinary Dental College. But support is growing among veterinarians for anesthesia-free dental exams and cleanings under certain circumstances. Regulation of the practice varies by state.

Dr. Kate Knutson got the call near the end of February. The American Animal Hospital Association no longer wanted her to be its representative to the House of Delegates, the American Veterinary Medical Association's largest policymaking entity.

Knutson recently had been named to the board of Animal Dental Care, a provider of anesthesia-free cleanings and examinations in veterinary practices. The appointment, AAHA officials said, represented a "clear conflict of interest" given that AAHA opposes non-anesthetic dentistry under most circumstances.

Having spent five years as AAHA's alternate delegate to the House, Knutson recalls feeling shocked. "It was really very sad," she said.

Knutson's dismissal reflects an escalating level of tension over whether anesthesia-free dental prophylaxis falls below the standard of care, a topic that's generated controversy for more than a decade. Non-anesthetic dental scaling, commonly referred to as NADS, has gained traction among owners who want pet dental care without the expense and risks of anesthesia. Veterinarians who believe that cleanings and examinations can be done without sedation sometimes offer it in their practices.

They're in the minority, going against established thinking. Much of the profession objects to non-anesthetic dental cleanings because the procedures are believed to do little to promote long-term oral health. Critics say the use of a scaler — a dental instrument used to remove plaque and tartar from teeth — can pit tooth enamel and create more places for plaque-causing bacteria to settle. What's more, the restraint techniques used during anesthesia-free cleanings can cause injuries.

That was the case in California, where regulators cracked down on the use of scalers by anethesia-free teeth cleaners after a groomer allegedly broke a dog's jaw while cleaning its teeth. The use of a scaler in California is considered the practice of veterinary dentistry and may be used by a non-veterinarian only when under a veterinarian's supervision, Valerie Fenstermaker, executive secretary of the California Veterinary Medical Association, explained.

The regulation aims to take scalers out of untrained hands, Fenstermaker said. Many states have similar restrictions.

The profile of NADS providers, however, has evolved beyond grooming facilities. Today, a handful of companies offer what some believe to be higher-quality services inside practices, contracting with veterinarians and working under their supervision. Animal Dental Care is the largest of these with a presence in 17 states, California included. Florida-based Pet Dental Services is another company that, according to its website, employs "highly skilled hygienists."

Both companies are selective in the patients they accept. Neither works on animals with behavioral issues or medical conditions such as gingivitis, fractured teeth or abscesses. Technicians, advocates for anesthesia-free services say, use patience and training to scrape and polish the teeth of alert animals. "Some patients aren't a good candidate for us," Animal Dental Care COE Ken Kurtz said. "We did 45,000 cleanings last year and referred over 12,000 to anesthetic dentals."

The fact that new-generation non-anesthetic dental providers are more discriminating has led to a growing number of general practitioners advocating for safe and thorough anesthesia-free cleanings, even as many board-certified veterinary dentists warn that it's impossible to properly examine the teeth of an alert animal and to chip tartar and plaque from beneath the gum line, where disease can start and fester.

Those dueling philosophies have the profession talking. Dr. Jan Bellows, a board-certified dental specialist and president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry, said it was all he heard about during the North American Veterinary Conference in January in Orlando.

"It got to the point where I couldn’t go to the bathroom without someone in the next stall asking me, 'What do you think about anesthesia-free dentals?' " he said. "It's really pervasive."

To Bellows' mind, the key question is, "Does the animal benefit from the procedure?" He doesn't think so. "The short answer is no, because [the practitioner is] removing plaque and tartar, which may or may not even be a medical issue, but at the same time, they’re not able to treat anything."

A thorough dental procedure, he said, includes nothing less than a tooth-by-tooth exam, tooth-mobility tests, probing and radiographs: "This just cannot be done without anesthesia. Sixty percent of the tooth is located under the gum line, you can't see pathology without radiographs, and dogs and cats can't tell their dentist where the pain comes from. Dogs and cats have to suffer silently, and we can't thoroughly assess their dental health without anesthesia."

Evolving mindsets

Last month, The American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) launched a website to deter pet owners and veterinarians from considering anesthesia-free dental cleanings in any context. "Teeth that have been scaled and not polished are a prime breeding ground for more bacteria growth which perpetuates oral disease," the website states. "Anesthesia free dental cleanings provide no benefit to your pet and do not prevent periodontal disease at any level. In fact, it gives you a false sense of security as a pet owner that because the teeth look whiter that they are healthier."

Knutson, the former AAHA president and alternate delegate, used to agree. In 2012, she co-authored AAHA's guidelines that direct member hospitals to steer clear of anesthesia-free dental services. "Techniques such as necessary immobilization without discomfort, periodontal probing, intra-oral radiology, and the removal of plaque and tartar above and below the gum line that ensure patient health and safety, cannot be achieved without general anesthesia," the guidelines state.

The organization followed with a mandate in 2013 that all AAHA-accredited hospitals anesthetize and intubate patients undergoing any dental procedures, cleanings included. By July 2014, the topic was before the AVMA House of Delegates, where Knutson, as AAHA's alternate delegate and acting on its behalf, was among those who voted to amend the AVMA's dentistry policy to include an anesthesia directive.

Privately, however, she had adopted a new line of thinking. Animal Dental Care CEO Ken Kurtz, reeling from lost business after AAHA took its position, invited Knutson to see the company's techniques. "I said, 'You’re making the statement without seeing what we do,' " he recalled.

Knutson accepted. After observing Animal Dental Care technicians clean and probe the teeth of alert pets, she's concluded that anesthesia-free dental cleanings can be part of an oral health care plan, somewhere between screening and detection. "It’s not a replacement for X-rays and oral surgery," she said. "But Animal Dental Care is going under the gum line and cleaning out plaque and tartar. I’ve watched them do it over and over."

Plenty of veterinarians remain unconvinced and Knutson, pressing the profession to reconsider anesthesia-free dentistry, is attracting heat from colleagues.

On the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, a message board thread with 320 comments is littered with criticism of Knutson, many pointing out that she's not a board-certified veterinary dentist nor does she hold any advanced dentistry certification.

Knutson attributes those reactions to a fear of change. "Every time you have something new happen in medicine, there’s shifting," she reasoned. "Because medicine is elastic and dynamic, there’s always going to be room to make changes."

Just as no two practices are alike, neither are dental care services, and Knutson attributes much of the profession's disdain for anesthesia-free cleanings on poor definitions and preconceived notions. Knutson is such a believer that she serves as Animal Dental Care's medical director in addition to sitting on the company's board. Her own practice in Bloomington, Minnesota, however, does not offer the service because it's AAHA-certified, and the standards for certification do not allow it.

Knutson wants to amend the work she did for AAHA 2012, and prove that anesthesia-free dentistry has a place in the dentistry standards. She's pushing for a moderated talk on the topic during AVMA's annual meeting in August in San Antonio.

Knutson hopes AAHA will consider the same.

"I respect and adore AAHA, but I have to do right by my patients," she said. "In a dog that has no existing disease, no separation (of the gum and teeth), it’s possible to clean their teeth this way. And as soon as studies indicate that science supports that, I will petition AAHA to change their mind about this."

So far, AAHA leaders are electing to maintain the group’s anti-NADS guidance and refusing to bend hospital accreditation requirements that bar certified practices from offering anesthesia-free dental procedures. "In order to become AAHA-accredited, a practice must be evaluated on and pass this standard," said Kate Wessels, AAHA spokeswoman.

Wessels noted that some AAHA-accredited practices have canceled their memberships because of the mandatory dental standard; she did not say how many. Some 3,600 practices throughout the United States carry AAHA accreditation by meeting roughly 900 standards.

AAHA wants to see more evidence before considering whether to make changes, Wessels said. "As research becomes available and the advice of boarded specialists evolves, so do the AAHA standards," she explained. "There is much common ground here, as we all want the same thing — the best medicine and care for veterinary patients."

Science behind plaque, tartar

To some observers, non-anesthetic dental scaling might seem like a benign procedure. Humans, after all, get their own teeth cleaned every six months without undergoing anesthesia.

It’s not that simple, though, said Dr. Colin Harvey, a professor emeritus of Surgery and Dentistry at the University of Pennsylvania's veterinary school and a leading expert on periodontal disease. Harvey recently ended 10-plus years as executive secretary of the American Veterinary Dental College, the clinical specialist organization for veterinary dentists.

Harvey acknowledged that in a cooperative dog with no existing dental disease, a skilled operator theoretically could clean the visible surface of the dog’s teeth. But operators who aren’t veterinarians would not have the experience or skill to know whether there’s disease below the gum line, he said.

"The only way we can tell definitely," he said, "is by using a periodontal probe gently inserted under the gum to scratch the root surface to check for roughness caused by calculus (tartar) and to check the depth of the pocket between the root and the gum tissue. If the dog isn’t cooperative, there’s a risk of mechanical damage to gum tissue, and the operator can be hurt if the dog is objecting."

Bellows, president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry, noted that even some general veterinary practitioners fail to properly recognize when a dental cleaning is needed. That's because "virtually no training in dentistry is happening in veterinary schools, and if there is, it's being taught by general practitioners," he observed.

"Many veterinarians think that if the teeth look dirty, you clean them," Bellows said. But visible signs of plaque and tartar alone don't indicate that a cleaning is needed, he explained. Rather, bad breath and bleeding are signs that disease-causing anaerobic microorganisms are lurking under the gum line.

"The $64,000 question is which animals need to have their teeth cleaned, if at all," Bellows said. "The correct answer is, the ones that either have halitosis or the ones you can take a Q-tip around the gum surface and get a little bleeding. That's when you need to clean their teeth. It's the perfect time to catch this, when there's gingivitis but before periodontal disease."

’Corrosive’ impact on practice

Science aside, the past couple of decades have borne witness to the erosion of veterinary medicine as a business, with many private practitioners struggling to get by, as outsiders aim to take a piece of the animal-health pie. Online and retail pharmacies have entered the pet-medications market en masse, stripping veterinary practices of once-lucrative in-house pharmacies they relied on to offset expensive medical care. Charitable clinics seem to be popping up on every corner, using donations and tax breaks to offer low-cost spays and neuters, microchipping, vaccines and sometimes more, critics say, resulting in unfair competition for private practices.

Now lay dentistry is offering an inexpensive cosmetic shortcut to cleaning teeth that’s considered by many to be corrosive to both a practice's bottom line and the profession's medical standards. Recognizing this, proponents of non-anesthetic scaling insist that veterinarians simply want to continue to corner the market on dentistry and other ancillary services, either by enacting state regulations that bar non-veterinarians from cleaning pet teeth or requiring anesthesia be used during all dentistry procedures.

This is where the politics against anesthesia-free dentistry have hardened and intensified.

"Those that support this nonsense, you are shooting yourself (and the rest of us) in the foot," wrote Dr. Carl Darby of Seneca Falls, New York, in a VIN discussion. "Those companies that are butt kissing you and stroking your ego at the moment will be taking away a large percentage of your dental business in the next 10 years. You are helping fill their war chest to compete against you.

"Secondly," he added, "all those poor dogs with periodontal disease (which is 50 percent of dogs over 5 years of age) will live in pain with deceptively shiny teeth, and you will be complicit in covering up the suffering of these pets."

Like Knutson, Dr. John de Jong has drawn criticism. He went public with his support of anesthesia-free dentistry when he appeared in a news article published Jan. 13 in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. In it, de Jong stated that "a conscious dental cleaning can be a valuable adjunct to a complete and thorough oral health care plan," especially for clients who fear putting their dogs under anesthesia or balk at a the price tag.

The position alone would have made him unpopular among many of his colleagues. But de Jong is chairman of the AVMA Board of Directors, and the leadership position has made him a larger target. He's been lambasted on social media, where he's been referred to as "embarrassing" and "horrific." Some veterinarians are even calling for his resignation.

"I've never seen anything like it," he said.

De Jong explained that his stance on anesthesia-free dentistry evolved in 2012, after witnessing Animal Dental Care veterinary technicians clear visible tartar and plaque, even scraping below the gum line, from the teeth of his own dogs, who he says remained fully alert and relaxed.

"Watching that was a huge paradigm shift for me," he recalled. "I was impressed."

Soon after, de Jong began to offer Animal Dental Care services to his clients in Massachusetts, which he says wasn't a secret among AVMA board members when the group voted in 2014 to add a statement in favor of anesthesia to the group's policy on dentistry. The policy reads, in part, "procedures such as periodontal probing, intraoral radiographs, dental scaling and dental extraction … should be performed under anesthesia."

Critics of de Jong contend his association with the company conflicts with his duties as AVMA board chairman. De Jong declined to disclose his business arrangement with Animal Dental Care, apart from stating that his "belief in the modality has nothing to do with finances."

"I’ve seen it work," he said. "I really feel there's a place for it. It's basic assessment and conscious cleanings. Dentistry is a lot more, and to call this non-anesthetic dentistry is a misnomer."

Knutson makes a similar assertion, stating that she'd rather the profession view such anesthesia-free cleanings as preventive care.

"The word 'dental' has so many different meanings to everybody," she said. "What you have in your head is your own frame of reference."

In Knutson's practice, a 'dental' involves presurgical examination, appropriate blood work, catheterization and anesthesia. Teeth are charted, probed and polished. Full-mouth radiographs are taken. "But to someone else," she said, "a dental can mean that a patient is taken in a back room, where someone uses rongeurs to chip tartar off teeth. There's a real bell curve as to what's expected."

She added: "This cannot be done on a trash mouth. It’s for prevention; it’s true prophylactics."

Knutson believes all dental procedures should stay within a veterinary-client-patient relationship, anesthesia-free cleanings and examinations included. But such preventive care should be considered separate from true veterinary dentistry, she added.

"If there's a way for us to come up with preventative dentistry, this could be it," Knutson said. "For all my clients that brush teeth every day and do such a good job with their pets, anesthesia is expensive for their health care dollars. I think we can use this in addition to regular dentistry, as I do it at my hospital."

There isn’t enough science to show such cleanings work long-term to save teeth and prevent disease. "But common sense says it does. That’s why we brush our teeth every day," she said.

Call for research

Harvey, the periodontal disease expert and Penn professor, agrees that more evidence is needed to determine the impact of anesthesia-free dentistry on patients. "There are no well-conducted large-scale trials with appropriate controls that will allow us to say, 'Yes, in this circumstance; it’s helpful or not helpful,' " he said. "Until there are such trials, we’re all looking to make comments in a vacuum."

Without trials showing benefit, the profession must proceed with caution, he added.

"The dental college is taking the safe way out to say we’re treating animals under anesthesia," Harvey said. "If there aren’t trials showing a benefit, I doubt the AVDC will take a look at that."

Thus far, no single entity is leading the charge on studying NADS and its impact on patient health.

Pet Dental Services, the anesthesia-free dental provider in Florida, reportedly plans to move forward on a pilot study involving 12 dogs with the working title "A comparison of oral examinations and dental cleanings in non-anesthetized and anesthetized dogs." Chief executive officer Joshua Bazavilvazo spoke of the research in a recent JAVMA article, which noted that the study is being conducted by two veterinary dental specialists and two technicians.

"I know what we do is beneficial for the pet, and it is a viable medical procedure that can be proven," Bazavilvazo told JAVMA.

Pet Dental Services provides cleanings only under the supervision of veterinarians. Bazavilvazo, who did not return phone calls seeking comment, reportedly considers anesthesia-free cleanings to be complementary to cleanings performed under anesthesia. He said to JAVMA, "At every single practice that we work in, the anesthetic dentals go up because we find so much pathology just during our oral examination, before the dental is even started."

Knutson is putting together some research on canine cortisol levels to determine whether dogs are more fearful during an oral health-care screening than, say, a nail trim. "We’re starting by looking at the patients in my own practice," she said.

What’s missing, she added, is a good double-blind study performed at the university level that can identify whether anesthesia-free dentistry reduces the incidence of tartar and gingivitis in patients and its overall impact on their dental health.

"Ultimately, that’s where this needs to go," Knutson said. "It doesn’t matter which way this falls, we just need some evidence."