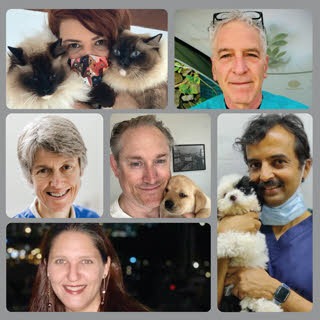

Collage world vets

Top row, from left: Dr. Raquel Calixto (Brazil), Dr. Jeffrey Bodan (Italy)

Middle row: Dr. Caroline Reay (England), Dr. Oliver Reeve (New Zealand), Dr. Makarand Chousalkar (India)

Bottom: Dr. Sarah Churgin (Hong Kong)

As COVID-19 took hold last spring, veterinarians from Asia to South America, and Europe to Australasia described in a series of VIN News Service articles how the disease and responses to the disease were affecting their daily lives and work.

VIN News recently caught up with most of these veterinarians to learn how they have weathered the past year. Here are their stories.

Hong Kong: Virus control — at a cost

For Dr. Sarah Churgin and colleagues at Ocean Park zoo and aquarium, working through the pandemic has been a bit like a ride on the park's Hair Raiser rollercoaster.

The Hong Kong theme park closed on Jan. 26, 2020, as virus fears mounted. It reopened a few times during the year but as infections rose, fell and rose again, the government mandated closures repeatedly.

The latest reopening was Feb. 18. Visitors have eagerly returned, Churgin reports: "Hong Kongers, just like everybody else in the world, are tired of COVID."

Throughout, Churgin and others involved in animal care remained employed, although for fewer hours and lower pay. Now they are back full-time but many remain on reduced pay while the nonprofit park copes with financial strain.

Dr. Sarah Churgin

Photo by Steven Ma

Dr. Sarah Churgin cares for aquatic and terrestrial animals alike at Ocean Park, where she is tested for the coronavirus every two weeks. The vaccine became available in mid-February but veterinarians are not among the top-priority groups in Hong Kong for inoculations.

Beyond financial constraints, the past year has been difficult emotionally. Churgin is from the United States; her family and many friends live halfway around the world. "Being an American abroad and watching everything unfold at home has been scary and sad and just really, really stressful," she said. Unable to safely and easily travel to visit family, she and fellow expatriates often have felt helpless.

It was also astounding to see how events unfolded. Living relatively near mainland China, where the novel coronavirus first broke out, Churgin expected early on to be at greater risk of infection than her family. Instead, she found, "The U.S. has really struggled and Hong Kong has really controlled COVID."

The territory, with a population of 7.5 million, has logged 11,151 cases and 203 deaths to date.

Actions there to control the virus have come, though, "at a huge cost," Churgin said. "The economy is destroyed."

At the same time, "My friends and I say to each other all the time, we're lucky to be here," she said. "We essentially have little to no worry about the threat of getting COVID ourselves. I don't know anyone personally who has gotten COVID in Hong Kong."

Italy: A 'period of great responsibility'

Dr. Jeffrey Bodan can bake a mean bagel these days, having had plenty of time to perfect his culinary skills during Italy's long and tortuous pandemic year.

Away from home, the veterinarian also has been working hard to make his small animal practice in Perugia accommodating to pet owners.

Bodan's bagels

Photo by Dr. Jeffrey Bodan

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Jeffrey Bodan began baking bagels, producing the pictured batch. Perfecting his technique through the year, he reported in December, "Getting better."

Dr. Jeff, as he prefers to be called, describes various modifications he's adopted to allow for safe visits, including constructing a sheltered outdoor waiting area. Inside, he's created four ventilated waiting rooms, each for a single client.

During exams, patients' owners may be present, staying in the doorway. Afternoons, Dr. Jeff employs telemedicine to stay in contact with clients and patients who do not need in-person visits.

One of the first countries in the world to be inundated with COVID-19 cases, Italy still ranks among the top 10 countries in cases and deaths — more than 3.1 million and 101,000, respectively. The country has a population of 60 million.

A hard lockdown imposed last March ended in mid-May but non-essential travel remains prohibited and there's a curfew, meaning "no late-night rendezvous with our friends and family," Dr. Jeff reported by email.

In sum, he said: "We are allowed to move around within our region once a day from 5 a.m. 'til 10 p.m., to go for food/essential shopping or to a home where only one or two people may visit another home. ...There are specific restrictions for restaurants, bars, shops and malls, while education, social interaction, health and sports have suffered, leaving many communities without a clear vision for their future."

Protection from the virus via immunization is on the way: His wife, a public school teacher, has received her first dose, while Dr. Jeff expects to be inoculated in late April.

As someone whose work was deemed essential from the start, he chafes at not being included with other health care professionals for early vaccination. Practicing veterinarians, he notes, "are continuously exposed."

The pandemic has led Dr. Jeff to reflect deeply on the meaning of his work. "[It] has strengthened my original desire to be a better veterinarian," he said, "especially now when we, as veterinarians, are called upon ... during this period of great responsibility, to maintain the human-pet bond and their safe survival."

Brazil: 'Chaotic' and 'terrifying'

Dr. Raquel Calixto

Photo courtesy of Dr. Raquel Calixto

Dr. Raquel Calixto visited her father on his birthday in November, making the difficult decision to prioritize his emotional well-being above the risk of infection.

The pandemic has reached a nadir for Dr. Raquel Calixto and her compatriots.

"It's a chaotic situation," Calixto, during a video call this week, said in English. "That's the best expression that I can find to realize you my situation, Brazil's situation." Calixto is a feline veterinarian.

Early on, decrees limited gatherings and movements around the country, and Rio imposed a mask mandate. Calixto's schedule was cut to two days a week and she saw only urgent cases. She worried about lost income, and kept herself isolated from others as much as possible. But by August, her clinic was operating at pre-pandemic levels and Calixto was back to a full-time schedule with no limitations on veterinary services.

Calixto is dismayed by how many people flout government restrictions. "I feel that too many persons think that it's OK. It's nothing. You know?" she said. "I see, every single day, full restaurants and full parties — parties! — and full bars; too many people in the streets. It's crazy."

Infections are spiking in Brazil, which has a population of about 211 million people, and a variant is overwhelming hospitals. More than 11 million people have been infected and more than 270,000 have died.

"Our numbers are terrifying," she said. "I feel more insecure than I've ever been."

Calixto is diabetic, putting her at increased risk of serious complications if she contracts COVID-19. Still, she has eased her isolation somewhat. "In a few situations, I need to see a friend in their homes," she said. "I've realized there is a thin line between mental health and body health."

The same consideration guided her thinking about her parents. Her father, who has Alzheimer's syndrome, became agitated by the solitude. She and her brother worried video calls weren't enough. They decided they had to visit their parents. "We knew it's dangerous to contact them, but actually we have no other choice," she said.

Recently, her parents received the first of two vaccinations, Calixto reported: "We are so happy."

London: A passion is reignited

Dr. Caroline Reay

Blue Cross photo

Dr. Caroline Reay practices in the United Kingdom, where the novel coronavirus has infected 4.2 million people and ended more than 125,000 lives — the most among European countries. She's pictured with co-worker Debbie Hodges and a patient, Tinkerbell.

Make no mistake, Dr. Caroline Reay is as over the pandemic as the next person. She and her colleagues at Blue Cross, a British charity that provides veterinary care to those of limited means, are so "fed up" with lockdowns, she says, they're getting outwardly cranky with testier clients.

But the London-based practitioner has found that working through the crisis brought a profound and unexpected benefit: It's helped her rediscover her connection with animals.

"It's interesting to see how much more relaxed animals are, now that they're coming in without their owners," Reay said by email.

Reay isn't sure why the animals are so chilled out nowadays. She wonders if it's because they're not picking up on the stress of owners, who are banned from accompanying them in exam rooms to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Perhaps not having to sit in waiting rooms near other animals and human children is a factor, she mused. Whatever the reason, pets' newfound placidity has been a delight.

"As a vet who's quite chatty and focused on the owners — I think history-taking is really important — it's been a surprise to me to rediscover how much I like working with animals!" Reay said. "We all talk to the animals, even though the client's not present."

An absence of owners from consultations also has given Blue Cross trainees room to learn techniques undistracted by interactions with clients. Older practitioners, too, have picked up new tricks, including how to examine patients remotely.

All the same, it's been a rough year. When VIN News spoke to Reay last May, a couple of her team members' relatives had come down with COVID-19, and one had lost their father to the disease. Since then, some staff have been infected — a few were "really poorly" — while others have lost relatives.

Blue Cross staff in an older age bracket or who have pre-existing conditions have been vaccinated. Reay can't wait for everyone to get a shot — even if that means getting less quality time with peoples' pets.

Mumbai: Optimism and vigilance

Dr. Chousalkar

Photo courtesy of Dr. Makarand Chousalkar

The team at Top Dog Pets Clinic in Mumbai, India, gathered for a photo today, exactly one year after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Dr. Sushruta Chousalkar, second from left, completed her studies and joined the practice during the pandemic. She stands to the right of her father, Dr. Makarand Chousalkar.

The pandemic yielded surprising professional insights for Dr. Makarand Chousalkar, chief veterinarian of a multi-doctor dog-and-cat practice in Mumbai, India, that he owns with his wife, also a veterinarian.

"We see retrospectively the impact of COVID-19 has been positive for us," Chousalkar said by email. "We are more disciplined and organized. [The] initial reduced number of patients gave us time to think and restructure our work style. Businesswise, we are getting better."

After a period of treating only emergencies, the clinic is open for all cases, at reduced hours. Pet owners are still not allowed inside; runners continue to provide curbside pickup and delivery of pets.

"We hear the stories that some clinics have made phenomenal business in some parts of the country," Chousalkar said. "At our clinic, we are still very cautious."

India, with a population of almost 1.4 billion, has recorded more than 11.2 million infections (second only to the U.S.) and 158,000 deaths (fourth highest in the world).

Chousalkar is heeding government warnings that the public not drop their guard even as the situation improves. "Though there has been a slight hike in the new cases, we were expecting [a] much worse spike … as public transport opened," he said.

Meanwhile, he said he doesn't mind losing some business until everyone is vaccinated.

That effort is well underway. Many on his team have received at least one dose. Veterinarians were prioritized along with human health workers; they have not, though, been asked to help with the vaccination drive thus far.

Jumbo COVID hospitals have been converted into vaccination centers. "There were some technical glitches initially regarding registration for vaccination, and apprehension amongst people and doctors about safety and efficacy," but people are becoming more confident, he reported, describing community morale as high.

"The vaccination drive has brought in new hope."

New Zealand: Normal with a background of anxiety

New Zealand

Photo by Dr. Oliver Reeve

Dr. Oliver Reeve recently celebrated the end of a 7-day lockdown in Auckland — spurred by a spike of cases at the border — by taking a hike on the coast with his 15-year-old son, Jack. They followed the Omanawanui Loop at Waitakere Ranges Regional Park.

When COVID-19 menaced New Zealand last year, Dr. Oliver Reeve wondered how he'd keep his practice afloat. Now, business is so good, he's worried about burning out.

Few countries of comparable size have managed the pandemic as well as New Zealand, a nation of 4.8 million people tucked in the southernmost reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

Thanks to geographic isolation, combined with strong border control, intermittent lockdowns and contact tracing, New Zealand has avoided community spread. So far, it's clocked 2,410 infections and 26 deaths.

"It's essentially been pretty normal with a background of COVID anxiety," Reeve, who is based in Auckland, said. The only persistent signs of the pandemic are masks on transit, scannable QR codes in businesses to assist contact tracing, and an ongoing international border closure.

Reeve wasn't sure it would turn out this way. Last May, coming out of the country's most sustained lockdown, his four-veterinarian companion animal practice faced a revenue drop of 40%. Reeve feared the economy would slow to the point where folks stopped spending on veterinary care, similar to what happened during the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

But that's not how it's turned out. "Demand came roaring back," he said. Regular clients turned up as normal and stopped delaying elective procedures. Plus, Reeve's seeing lots of new puppies amid a pandemic puppy boom.

He's optimistic and a bit overwhelmed. "I love being busy but if it is unrelenting for long enough, it does start to burn you up," Reeve said. "We had a vet meeting scheduled to talk about these problems. We had to cancel it because it was so busy."

As New Zealand doesn't have an especially urgent need to vaccinate its population, Reeve doesn't expect to be immunized until the second half of the year. Currently, the focus is on vaccinating border and quarantine workers and vaccinators, he said.

He's not worried about his place in line. "The way I look at it," he said, "as long as the vaccine is being rolled out somewhere, we are winning because we want people to come back to New Zealand."