Veterinarians can use remdesivir to treat lethal cat disease — if they can get it

Tyrian

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Reading

Tyrian got some cuddles from his owner Wednesday during his first treatment for feline infectious peritonitis, a deadly cat disease. The 1½-year-old tabby received an infusion of remdesivir, an antiviral that was the first approved treatment for Covid-19 in humans. The Gilead drug has been shown to be effective in reversing FIP, but veterinarians have had difficulty obtaining it.

This story has been updated to add the news that Canada is allowing veterinarians to import compounded treatments from the United Kingdom.

Dr. Anna Reading is doing what few veterinarians in the United States before her have done. The small animal practitioner in southern Washington state is administering an antiviral drug to a cat with feline infectious peritonitis, a fatal disease, without breaking any laws or regulations.

Her patient is a 1½-year-old tabby named Tyrian whom Reading examined in mid-January after the owner had reported that Tyrian "wasn't himself." He wasn't eating, he'd lost weight, and he had a fever. After bloodwork and an ultrasound, Reading narrowed her diagnosis to likely FIP.

The diagnosis was heartbreaking. Or it usually is.

FIP is a rare response in cats to infection by a common pathogen, feline enteric coronavirus (FECV). Generally, cats infected with FECV are asymptomatic and remain healthy. But occasionally, FIP develops because the virus mutates in such a way that it infects immune system cells, which disseminate and cause inflammation that is almost always deadly.

FIP most often occurs in young cats. Without treatment, they can die within months, weeks and even days after showing signs.

For the past five or so years, the only effective antivirals available to treat FIP in the United States were thought to be illegal imports procured by some owners on the black market. But thanks to Reading's perseverance, input from veterinary colleagues and the aid of personal friends, the doctor was able to prescribe legal remdesivir for Tyrian.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved remdesivir in October 2020 to be used to treat people age 12 years and older with Covid-19. Researchers in the U.S. and elsewhere have demonstrated that remdesivir can be an effective treatment for FIP, and the FDA approval effectively made the drug legal for veterinarians to use off-label — a development that has flown under the radar in many veterinary circles.

Remdesivir is closely related to another Gilead antiviral, GS-441524, one of the first antivirals shown to reverse FIP in cats. The research was done in the late 2010s at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine.

GS has not been through any formal drug approval process in the U.S. or elsewhere, but in the wake of the UC Davis discovery, manufacturers, mostly in China, started making versions of GS, which were promoted on social media and purchased by desperate cat owners willing to treat their pets on their own. As these unauthorized drugs saved cats, their reputation spread, and a black market for FIP drugs became well-established. Some veterinarians struggled to follow their ethical commitment to saving cats and helping their owners while providing care that wouldn't run afoul of FDA rules and cost them their licenses.

Reading was familiar with GS, having seen nearly a dozen FIP patients — though not all — cured with the treatment. Because it is not an approved drug, the veterinarian does not obtain or administer it — the owners take care of that. The doctor does provide lab work and treats injection-site reactions for cats being treated at home. GS has an acidic pH that makes the injections, which are generally given daily for a minimum of 12 weeks, painful. It can also cause sores.

The veterinarian told Tyrian's owner about GS. The owner found a source for the antiviral on her own and began therapy late last week. But the cat continued to lose weight, and bloodwork showed he was declining.

Reading conferred with an internal medicine specialist. The conversation was bleak. "We both looked at each other and kind of accepted, 'We're probably going to lose this cat,' " Reading said.

A little help from the community

In a last-ditch effort, she went online to UC Davis, which has been a leader in FIP research, and read a study that showed remdesivir can be an effective alternative for cats who are resistant to GS.

Reading asked the internist, "Can we get remdesivir?" The specialist was dubious. Undeterred, Reading checked another source.

"I went on to VIN ... and I found that thread," she recounted.

Update: Canada OKs FIP drug imports

"That thread" was a message board discussion on the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service. Dr. Caroline Bailey, a small animal veterinarian in Brunswick, Maryland, started the discussion out of frustration in November. She, too, had a very sick patient with FIP and had searched the internet for treatment options.

Early into her investigation, Bailey read about GS and remdesivir. The latter appeared to Bailey to be a fully approved treatment in the U.S. for humans, making it available for veterinarians to use. It is given intravenously to hospitalized Covid patients.

Her excitement turned to confusion when online source after online source claimed it was still off-limits.

She posted on VIN that she searched online and consulted with her husband, who is a regulatory scientist. "Neither of us can figure out why, in 2023, we can't prescribe remdesivir. … Yet, multiple websites from reputable sources still state that it is under emergency authorization," she wrote.

VIN consultants and other colleagues on the thread told Bailey she was right; the online sources were wrong.

Anne Norris, an FDA spokesperson, has since confirmed to VIN News that remdesivir, marketed as Veklury, was fully approved in October 2020 for the treatment of Covid-19 in patients age 12 and older. Therefore, since that time, veterinarians had the authority to use it off-label — or "extralabel" in FDA parlance.

What may have seeded confusion about the approval is the fact that the FDA kept an emergency use authorization in place until April 2022 for the use of remdesivir in patients under 12.

"Extralabel use of Veklury (remdesivir) is permitted for the treatment of cats with FIP if that use is by or on the lawful order of a licensed veterinarian within the context of a veterinarian-client-patient relationship and is in compliance with the Extralabel Drug Use regulations in 21 CFR part 530," Norris said in an email. The regulations limit use to situations where an animal's health is threatened or where it may suffer or die without treatment.

Learning from the VIN discussions that veterinarians can use remdesivir surprised Dr. Lauren Grider, a practitioner in Alabama. She wrote, "This needs to be on the front page; it's big news!"

Not only has the fact not been on anyone's front page, it hasn't been reported on correctly by a variety of reputable sources, including websites of professional organizations and veterinary schools and media outlets. That includes VIN News. (Those articles have been updated.)

What might be clouding the picture further is the fact that FDA approval has not equaled availability. Early in the pandemic, shortages of Veklury made veterinary use a nonstarter. But it's no longer in short supply, and some veterinarians say they still can't find a distributor or hospital to sell it to them.

Next hurdle: Getting ahold of the drug

Reading is the first veterinarian VIN News has spoken to who has successfully purchased Veklury. How she managed to get her hands on it, she said, "was just one of those things that the universe set up." She called a couple of pharmacies, compounding pharmacies and MWI Animal Health, a veterinary distributor owned by human medicine distributor AmeriSource Bergen, which distributes Veklury.

"I did a lot of, 'I'm calling this in for a cat named Tyrian. He's only a year old. He's an orange tabby. He's a family cat,' " she said. "You know: 'This is not just a number. He's a being who's loved.' "

Over and over again, she was told Veklury wasn't available.

Then, talking with a good friend who was also a client, the doctor happened to ask, "Hey, do you know anyone who works in a hospital pharmacy?" The friend did, and connected Reading to the contact via text. That person referred her to the pharmacy purchasing department for a local hospital pharmacy, where she left a voice message last Thursday. The purchasing department called her back Friday morning. By that afternoon, two 100-milligram vials of Veklury were ready for pickup at the outpatient pharmacy.

The pharmacy charged $594 per vial, close to the manufacturer's list price of $571. Reading said the two vials, all she can get, will be enough for four days of IV infusions, which the veterinarian hopes will stabilize Tyrian's condition. Then his owners will continue giving him GS injections in lieu of more remdesivir.

"The only reason I'm doing that is because I have no choice," she said. "I can't get any more. If I had a choice, I would continue him on this drug."

On Wednesday morning, after getting the results of a PCR test that helped confirm the disease, Reading began giving Tyrian his infusions.

Reflecting on the process so far, Reading said she feels grateful and lucky that she had a friend-of-a-friend connection with the pharmacy. "But I know that not everybody's going to have that, and you shouldn't need to have that access. It should be available," she said.

Reading probably isn't alone in using Veklury, but she appears to be part of a still-small group. A poll of VIN members conducted in January asked veterinarians if they had used remdesivir and/or GS. Of more than 2,700 respondents, 22 U.S.-based veterinarians said they had used remdesivir.

Bailey, who started the online discussion that stoked the fire under Reading, wasn't able to help her patient in November. That cat died without treatment within days.

Why the mystery?

Why don't more veterinarians know that remdesivir is approved and potentially available for them to use?

When asked what he thought, Dr. J. Scott Weese, an infectious diseases veterinarian at the University of Guelph's Ontario Veterinary College, said: "I think it's because we haven't been able to get easy access through the legal routes in the U.S. While there should be no barriers to getting it through medical suppliers now, actually getting the drug seems to be a hurdle still. Hopefully, that will get sorted out."

Dr. Vicki Thayer, who is board-certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners in feline practice, said she has heard about roadblocks to access. Thayer is director emeritus at the EveryCat Health Foundation, which funds feline health research, including FIP studies.

"Likely Gilead and government regulatory agencies restrict the ability to purchase the drug in specific situations and specific sources for humans, and these are not accessible for veterinarians to get remdesivir," Thayer said.

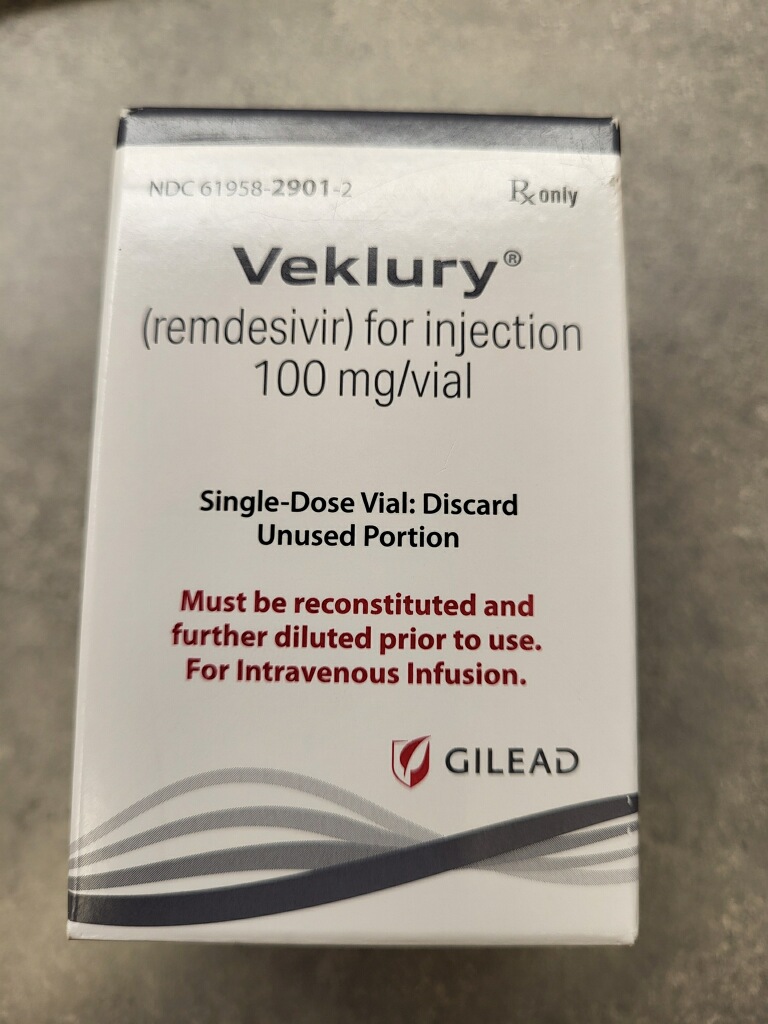

Veklury for Tyrian

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anna Reading

A practitioner in Washington state, Dr. Anna Reading, obtained two vials of Veklury (remdesivir) from a human hospital pharmacy, using informal connections. Although relieved to procure a legal treatment for a sick patient, Reading is frustrated that the drug isn't readily available to veterinarians.

These specific sources likely include in-hospital pharmacies and specialty pharmacies that supply human hospitals. They may be restricted or believe they are restricted from selling or distributing remdesivir outside of the human hospital setting.

Other veterinarians who spoke to VIN News echoed the opinion that remdesivir has been essentially walled off from veterinary use — exactly why or how is unclear.

According to Gilead product information, Veklury can be purchased from AmeriSource Bergen, Cardinal Specialty and McKesson. Neither Cardinal nor McKesson responded to multiple inquiries from VIN News about the availability of Veklury for veterinarians. A spokesperson for AmeriSource Bergen confirmed only that MWI Animal Health does not distribute or sell Veklury.

Gilead, for its part, has been quiet about GS and remdesivir for veterinary use. After GS showed promise in FIP studies at UC Davis in the late 2010s, the company stopped providing its antivirals to the school's researchers, according to Dr. Brian Murphy, a veterinary pathologist at UC Davis, who was involved in the research.

Over the years, some veterinarians and cat owners have lobbied the company to bring GS to market. Neither public cajoling nor the thriving black market in knockoffs has persuaded Gilead to act.

In early 2021, a Gilead spokesperson told VIN News that the company was exploring working with other parties on pursuing options for out-licensing GS for veterinary use. The company did not respond to recent queries from VIN News asking about its plans for GS and the availability of remdesivir in the U.S. and Canada.

Dr. Dawn Boothe, a veterinary internal medicine specialist and clinical pharmacology consultant for VIN, said there are several reasons Gilead might avoid commenting on or encouraging veterinary use of remdesivir.

"What they may be afraid of is that if we have adverse events to this drug in our patients, we're going to report them," she said, "Then, that is potentially going to raise red flags to the FDA."

Another issue for Gilead, she suggested, is: "If they in any way, shape or form are perceived to be promoting the extralabel use of this drug in animals, the FDA is likely to be unhappy about that promotion," owing to the fact that drug manufacturers are not permitted to tout extralabel use.

Veterinarians in Canada also are stymied in their efforts to obtain Veklury for their patients. According to a Toronto Star story published in December, Gilead will not allow the drug to be sold for pets in Canada, even though it is approved for human use there.

Health Canada's Veterinary Drugs Directorate could not explain the reason. "Companies are not required to provide this information to Health Canada," an agency spokesperson said in an email.

Weese, the veterinary infectious diseases expert based in Ontario, said, "[A]ll of the Veklury that's here is through government procurement and goes directly to specialized hospital pharmacies. There's no distribution system and Gilead won't sell it directly, so we're stuck."

What about compounding?

Dr. Ron Gaskin, a practitioner in Minnesota, said he would like to see compounded versions of remdesivir. "The compounded drug would be cheaper and in aliquots more suitable for cat dosing without waste," he said.

Compounding animal drugs is the practice of preparing custom medications tailored to the needs of an individual or a small group of animals. According to FDA guidelines, a drug can be compounded "when there is no medically appropriate drug that is FDA-approved … to treat the animal."

Approved but not, in practical terms, available, remdesivir would appear to fall between the cracks.

Gaskin said he's called at least a dozen U.S. veterinary compounders with his proposal, and none has responded. He speculated to VIN News, "There's no U.S. compounding because Gilead would crush them like a bug."

Whether compounding is an option in the U.S. is something Boothe, the clinical pharmacologist, has been researching for a new monograph about remdesivir and GS for the VIN Veterinary Drug Handbook.

"We've got a pretty hazy line here; I think you can say that," Boothe said about remdesivir. "What constitutes not being able to access it is not clear. I would say if you've made a reasonable attempt … and you can verify that, the FDA would, should, allow regulatory discretion."

However, in February 2021, FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research issued an alert cautioning against compounding remdesivir drug products and recommending that health care providers use the FDA-approved drug. "Complexities related to the quality and sourcing of the remdesivir active pharmaceutical ingredient and formulation of remdesivir drug products may make these drugs particularly challenging to compound," the alert warns.

Compounded versions of GS and remdesivir are legally available for veterinary use in parts of Europe and Australia. The products are produced by Bova, a veterinary pharmaceutical company in the United Kingdom and Australia under guidance from the U.K.'s Veterinary Medicines Directorate.

Gaskin said he contacted Bova about importing the compounded medicine, but when he told the representative he was in the U.S., he was told they couldn't sell it to him.

Another antiviral could be on the way

Meanwhile, another antiviral, GC376, is being developed specifically for veterinary use. Known by the shorthand GC, the compound has been demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to be effective in treating FIP.

Like GS, versions of GC have been produced for the black market and funneled illegally to the U.S. Pet owners told VIN News in 2019 that they have used black-market versions of GC to cure their cats. However, GS has generally dominated illegal sales.

In a study published last month, researchers tested the purity of 30 unregulated products. Of five that were sold as GC, one contained GS and the other four contained molnupiravir, another antiviral used to treat Covid-19.

The patent-holder for GC, Kansas State University, has licensed the veterinary biotech company Anivive Lifesciences for the development of GC. The company is well down the road of working toward bringing an injectable drug to market, according to Anivive's chief medical officer, Dr. David Bruyette.

Bruyette said in January that Anivive is working toward conditional FDA approval for GC. Under conditional approval, which can last for as long as five years with renewals, the company could sell the drug legally for its labeled use — treating FIP in cats — while it collects additional effectiveness data needed for full approval.

"If all goes swimmingly well, GC could be approved by 2026," Bruyette said. "The world is in dire need. People want a safe and approved product, so they don't have to play roulette."