Tina and Makeba

Photo by Morrell Gray

Tina, left, arrived on the doorstep of Southwest Veterinary Clinic when it reopened last year under the new ownership of Dr. Makeba Clarke. The cat was welcomed as a talisman and has made herself at home.

This is the first of two parts. Read part 2.

The very first patient at Dr. Makeba Clarke's companion animal hospital was a hungry cat that someone dumped, along with a litter box, on the clinic doorstep.

Another first-time practice owner might have been discouraged by this dubious form of welcome, but not Clarke. The cat had tortoiseshell markings, which Clarke cheerfully interpreted as a sign. In Barbados, where her family is from, tortoiseshell cats are called money cats, she said: "They're supposed to bring you good luck."

Clarke fed the abandoned animal, brought her inside, spayed her and named her Tina. Today, one year later, visitors to Southwest Veterinary Clinic in Atlanta are apt to find Tina lording over the reception area, relishing her role as the clinic cat. And Clarke, looking back on a first year in business marked by a pandemic on top of the usual struggles of a startup, says that on balance, yes, Tina brought good luck.

Finding good fortune in unfortunate situations is a gift that has helped Clarke, 38, navigate a rocky path to the veterinary profession and entrepreneurship. Like so many of her colleagues, Clarke was born with a love of animals and wanted from the time she was a kid to make sick animals healthy. But as she described in a series of interviews with the VIN News Service, becoming a veterinarian, much less a practice owner, was far from inevitable.

Big-picture economic and demographic realities were not in her favor.

Economically, veterinary private practice in the U.S. is coming under increasingly consolidated ownership, whereby large corporate owners, many funded by private equity investors, control ever greater numbers of clinics and hospitals. Single-location owner-operated practices like Clarke's, once a mainstay of veterinary medicine, are no longer the norm.

Demographically, the veterinary profession is racially homogeneous. Nine out of 10 veterinarians in the United States are white. Black veterinarians number somewhere between one and three out of 100. So role models for Clarke, the daughter of Black immigrants from the Caribbean, were scarce.

Growing up, Clarke didn't ponder such macrocosmic trends. Her immediate problem was getting through the education necessary to become a veterinarian. She was nearly expelled from high school, had a bad first away-at-college experience and, for a time, hung in limbo at community college, distracted by parties and nightlife. But time and again as a student and young adult, with the help of a few encouraging words during pivotal moments, she turned setbacks into opportunities.

'You want to be a vet?'

Makeba and Muffin

Photo courtesy of Dr. Makeba Clarke

Muffin was a grumpy dog with an explosive personality but little Makeba wasn't afraid of him.

Even after being bitten in the face by a family pet named Muffin, 4-year-old Makeba Clarke constantly wanted to be around animals. She still has a small scar by her lip, but she never blamed the dog. "I guess he was sick and not feeling well," she explains in his defense.

The neighborhood where she and her siblings lived with their single mom, in a part of Boston known as Mattapan, was home to colonies of stray cats. "The kittens all had something going on with their eyes," she remembered — something gooey that didn't seem right. She'd bring cats home and ask if she could keep them. (The answer was no.)

When, early in grade school, Clarke heard the word "veterinarian" for the first time and learned that there was such a thing as an animal doctor, she was overwhelmed with delight. "Imagine you're a person who likes to eat pink Starburst," she said, "and you find out there's a person whose job is to eat all the pink Starburst."

But by middle school, she stopped saying she wanted to be a veterinarian. "I wasn't sure I could be one," she said. "I wasn't the worst student ever, but I wasn't the best, either."

Her mother, who worked in social services, is the kind of person who doesn't see barriers, but other adults were less than encouraging. "Oh, OK, the person who doesn't do her homework on time all the time, you want to be a vet?" Clarke said, imitating the skeptical tone she heard. "You want to be something that takes a lot of focus? OK, you could, but you gotta do better in science class."

High school was challenging in a different way. Clarke rode a bus two hours one way from her inner-city Boston neighborhood, inhabited predominantly by immigrants and people of color, to an academically rigorous school in a mostly white suburb. (Created in the 1960s, the voluntary school integration program called METCO, or the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, is still in operation.)

Staying motivated to take that long bus ride became nearly impossible after Clarke got her first job, at a copy shop. "I'm making my own money now, $6 or $7 an hour, and then slowly not doing well in school anymore. I'm missing days. School seemed too foreign to me at that point. I'm living in Boston, but I'm going to school in a different town, where kids got cars when they were 16, lived in mansions, it looked like to me, and had maids."

Senior year, Clarke nearly got kicked out of school. "I wouldn't, I couldn't, get up" in the morning, she said. "My bus would come at 6 a.m., and I didn't want to wake up and wait in the cold."

A school counselor encouraged Clarke to get a meaningful job or internship and keep a journal. Clarke landed an internship at Franklin Park Zoo, where she helped zookeepers in the tropical forest exhibits clean and prepare diets for gorillas and sloths. She earned English credit for the journal, enabling her to graduate on time in 2000.

For college, Clarke wanted a big change. Thinking "I'm done being the token Black girl!" she applied and was accepted to Clark Atlanta University, a historically Black college in Georgia. But she stayed only a semester, following a fistfight with a housemate who she said tried to boss her around. Describing the incident later, Clarke said, "I never really had a submissive personality."

But the conflict was traumatizing. Defeated, Clarke retreated to Boston. Her mom allowed her home on two conditions: "You have to go to school and you have to work full-time."

'What are you doing here?'

Clarke returned to a job that she had briefly in high school, working at a "chichi, froufrou" gym and spa for women. She enrolled at Roxbury Community College. "At the time, I was embarrassed to go there," she admitted. "I was coming from a public school system that I would say is one of the best in the country, consistently top 10 in Massachusetts. My friends from high school are at Brown, at Harvard. I was, like, Makeba the METCO student going to RCC."

She drifted for a few years, prioritizing her social life, staying out all night with pals. In 2003, several things happened that spun her around: Two close friends died from gun violence. Others were landing in jail. Lost and distraught, Clarke asked herself: "What am I doing with my life?"

Around that time, a friendly woman at the gym who bought smoothies from Clarke every day asked the same thing. "What are you doing here? What's your plan?"

Kid drawing

Photo by Dr. Makeba Clarke

Dr. Makeba Clarke's mother kept this grade-school drawing her daughter made of herself as a veterinarian. When Clarke graduated from veterinary school, her mom gave her the picture in a frame.

Clarke confessed to wanting to be a veterinarian, even though that seemed as attainable as becoming an astronaut. The woman said she knew someone who'd gone to veterinary school at Tuskegee University, a historically Black college in Alabama. The veterinary school is the reputed alma mater of more than 70% of Black veterinarians in the United States. Clarke had heard of Tuskegee but did not know it had a veterinary program. For that matter, she'd never met a veterinarian who was Black.

The woman at the gym introduced Clarke to Dr. Alfred Gaskin, a contractor in laboratory animal care. He encouraged her to take charge of her life, starting with seeking a raise at work. Newly pumped with confidence, Clarke asked for $2 more, over her $8-an-hour rate.

She was shot down. "They called this big meeting, all to tell me that I wasn't going to get $2 [because] I didn't do $10-an-hour work," she recounted. "They gave me 5 cents."

Humiliated, Clarke retreated in tears to a bathroom. A gym member she didn't know asked what was wrong. Clarke told her everything.

"One day," the stranger offered, "you're going to look back at this and laugh. This is probably what you need to get out of here and go be a vet."

Reflecting 17 years later, Clarke believes the woman was exactly right. If she'd gotten the raise, she might still be at that gym, "making maybe $12 an hour by now," she said dryly.

'You have to give yourself a chance'

Spurred to leave, Clarke applied to veterinary clinics and other organizations providing animal care. Gaskin introduced her to Dr. Donna Matthews Jarrell, then associate director of the Center for Comparative Medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital Research Institute. The center oversees the welfare of laboratory animals there, mainly small animals such as rodents. There are also larger animals in the mix; Clarke helped take care of pigs, sheep and nonhuman primates.

The environment elevated her sense of responsibility and importance. "You have [security] clearance, you have badges to go through locked doors. People were like, 'What's going on on the 6th floor?' and you know what's going on on the 6th floor. There are 401Ks and a big lunch room."

Clarke imagined becoming a lab-animal tech. She shared her vision with Jarrell. "Um, I did not have plans for you to stay here forever," Clarke heard Jarrell say. "I really felt like when we met, you wanted to be a vet, and you have to give yourself a chance."

Clarke deeply admired this woman, the second Black veterinarian she had ever met. She wanted to be equally poised and professional. Jarrell's words to Clarke, then 21, hit home.

If Jarrell made an impression on Clarke, Clarke made an impression on Jarrell, too. Part of Jarrell's job was mentoring students from Roxbury Community College who were interested in medicine, biomedicine or health care. Rarely did she meet one aspiring to a veterinary career; even rarer, a Black or Latinx student who wanted to be a veterinarian.

Graduation

Photo courtesy of Dr. Makeba Clarke

Dr. Makeba Clarke is flanked by her father, Leroy Cameron Clarke, and mother, Betty Padmore, at Tuskegee University College of Veterinary Medicine graduation in 2012. Although he left the household when Makeba was a baby, her father remained in her life until his death this year. Her steadfast mother raised three daughters and a son solo.

"I remember Makeba very well," Jarrell, now director of Mass Gen's Center for Comparative Medicine, told VIN News. "I remember her really trying to figure out the whole thing, what it takes. It's a commitment. ...

"I'm so proud of Makeba because I saw her at her most authentic self, kind of coming out of her community and learning how to move into where she wanted to go," Jarrell said. "I was there when she was starting to set the path toward everything she's accomplished."

With Jarrell's gentle kick in the seat, Clarke finished community college ("a two-year school that took me three years to finish") and got into Tuskegee, where she finished a bachelor's degree in biology and applied to Tuskegee's veterinary school. After a few agonizing months on the wait list, she was admitted.

But again, graduating wasn't a foregone conclusion. Unaccustomed to the pace, she nearly flunked out the first semester and constantly doubted her right to be there. "I am not like these people. How did I get into vet school?" she wondered. Even still, she earned her DVM in 2012 at the age of 30.

'What scares you the most?'

Clarke's first job as a veterinarian was with the largest veterinary practice in the world, Banfield Pet Hospital, which had upwards of 800 locations at the time. Clarke started at a clinic in Orlando and soon transferred to a new practice in Savannah, Georgia, where she was appointed as chief-of-staff trainee.

The experience was exhilarating, initially. "Banfield invests a lot into their associates and their leadership," Clarke said. "I was able to go to Portland [Oregon] to their headquarters twice. We went through some emotional intelligence training. We talked a little bit about the numbers and the corporate side and their principles and what they really mean in action. It was really nice. It was like a utopia for corporate. I really bought into it." She thought about getting an MBA and pictured one day becoming CEO of Banfield.

Three years along, though, the situation soured. No longer feeling supported, Clarke decided to quit. Adrift, Clarke asked one of her sisters, Sharon, what she should do next. Sharon replied, "What scares you the most?"

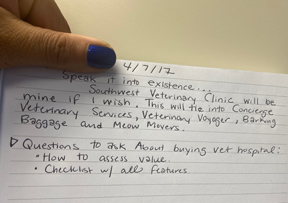

Journal

Photo by Dr. Makeba Clarke

In her journal, Dr. Makeba Clarke memorialized the day she was invited to consider buying a veterinary clinic in Atlanta. The entry includes other business ideas she had.

The answer: "Emergency medicine."

"Go do that," Sharon said. "At Banfield, you complained that you were afraid of doing C-sections and that you had never done an amputation. You don't feel like a vet; you feel like a corporate girl."

Clarke heeded the advice, taking a job at an emergency hospital in Locust Grove, Georgia, an experience she found paid off immensely. "In almost two years [there], I grew probably the most as a doctor," Clarke mused. "I started trusting my voice. At 2 in the morning, there are not a whole lot of people to ask [for another opinion]. At some point, you said, 'OK, Makeba, with all the information provided, you're going to make the best decision right now.' So that's what I learned — doctor confidence."

On April 7, 2017, confidence and chance came together: Clarke was offered an opportunity to own a veterinary clinic. She recorded the moment in her journal.

"Speak it into existence," she wrote.

Part 2: How one independent veterinary clinic was born

This story has been revised to clarify the members of Clarke's family.