How easing the shortage of physicians 60 years ago created opportunities, friction

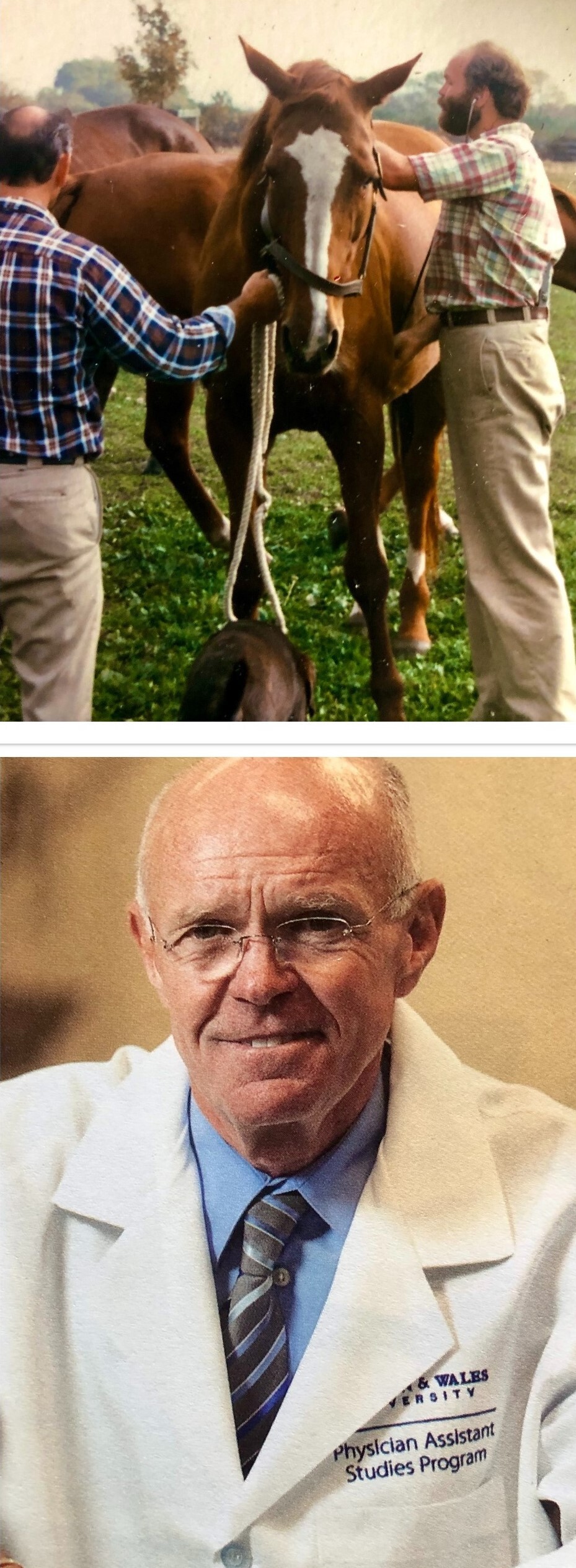

Dr. George Bottomley

Photos courtesy of Dr. George Bottomley

Dr. George Bottomley spent the early part of his medical career as a veterinarian. He's shown (at right in top photo) making a barn call in 1977. Bottomley later became a physician assistant, went on to run several PA programs in the country and most recently was the inaugural dean of the College of Health & Wellness at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Dr. George Bottomley was a 44-year-old mixed animal veterinarian doing a comparative medicine residency when a course in human clinical pathophysiology sparked an urge to become a primary care physician. A friend later convinced him that becoming a physician assistant would be more cost-effective and still allow him to practice with relative autonomy.

"For two years of my life, rather than four-plus, and with significantly less debt, I could graduate with the ability to practice medicine," he said. "I never looked back."

Now retired after 20 years as a physician assistant — also known as a physician associate or simply PA — as well as an educator and school administrator, Bottomley supports creating in veterinary medicine a role comparable to PAs or nurse practitioners (NPs).

"Looking back now, a PA/NP-type provider could undoubtedly have improved the quality of care for the animals in my practice by sharing (delegating) the workload and allowing for a less stressful practice environment and improved access for those who wanted to be seen," Bottomley said by email.

Veterinarian shortages, problems with staff attrition and retention, and frustration over a lack of advancement opportunities for veterinary technicians are among the drivers of a movement to create a midlevel practitioner role in veterinary medicine. Proponents point to the human medicine experience for inspiration. Opponents look to that same experience and see reasons for concern.

PAs and NPs, who generally refer to themselves as advanced practice providers, are a rapidly growing segment of the medical profession. (PAs and NPs who talked to the VIN News Service eschew the descriptor midlevel, believing it demeans the role.) The providers fill gaps where physicians are hard to come by, both on health care teams and increasingly as solo practitioners. While interviews with providers and employers indicate that patients, physicians and employers generally accept and respect these non-physician providers, organized medicine fights attempts to expand their scope of practice.

The PA and NP professions have existed for over a half-century, but tensions persist between organized medicine and PA and NP advocacy groups.

PAs and NPs argue that they provide high-quality, cost-effective care and increase access for people in underserved areas. They boast lower malpractice claim rates than physicians and push to gain legitimacy through advanced education and training.

The American Medical Association lobbies vigorously against what it views as encroachment on the duties and responsibilities it believes should be physicians' alone — a concept known as "scope creep." Despite its activities in the arena, the AMA declined an interview request.

But Dr. Rick Snyder, president of the Texas Medical Association, echoed the AMA's official position in saying that the more extensive training required to become a doctor makes a difference.

"Captain Sully didn't land that plane right out of pilot school," Snyder said, referring to a lifesaving maneuver in the Hudson River by commercial pilot Chelsey "Sully" Sullenberger in 2009. "He had lots of training in that plane. That's the type of judgment you need."

The professional divisions are so contentious that a new organization, Physicians for Patient Protection, has formed "to ensure physician-led care for all patients and to advocate for truth and transparency regarding healthcare practitioners." The group argues that NPs and PAs lack sufficient training to safely care for patients without physician supervision. They and other opponents generally hold that scope-expansion efforts amount to attempts to replace physicians. They support instead shoring up the pipeline to produce more medical doctors.

Roles and rules

NPs and PAs alike are trained to diagnose and treat patients, order tests and labs and prescribe medications, assist in surgery and work in all health care settings, such as community clinics, hospitals and private medical practices. State laws define the scope of practice for NPs, and PAs must pass a certifying exam for licensure in all states.

PAs work under some level of physician supervision or collaboration in all states, although a physician does not need to be physically present for a PA to provide service. In more than half of states, NPs can work without physician supervision. In primary care and some specialty areas, there is no difference between what PAs and NPs can do and what physicians can do. In surgery, however, while PAs and NPs with additional training can assist with an operation, they generally cannot operate on their own.

Depending on the health care setting and structure, physician supervision can mean having a doctor on site or being available by telephone and reviewing charts periodically.

Amy Marie Sorgent, a family nurse practitioner now overseeing care for hospice patients in San Diego, was hired out of NP school to run an occupational health and wellness clinic within a large corporation. In this role, she conducted physical exams for employees, managed workers compensation cases and lectured employees on how to stay healthy.

"I was the one-man band there," she said. "The doctor I coordinated with was living in D.C. He came out two or three times a year to review my charts." Fortunately, she said, she could refer employees to a primary care physician if needed.

Bottomley, the former veterinary practitioner, said that as an early-career PA, he was allowed to see primary care patients with relative autonomy after proving himself competent at a rural community health center in New Haven, Connecticut.

"I did everything from initial or regular visits to walk-ins and follow-ups, prescribed medication, developed diagnoses and treatment plans," he said. "If I had a problem or a challenging patient, I would bring that to the supervising physician in the facility just like a physician or NP would."

Organizational enmity, real-world amity

Dr. Rebekah Bernard, a primary care physician in Florida, president of Physicians for Patient Protection and author of a book titled Patients at Risk: The Rise of the Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant in Healthcare, rejects any scenario that largely grants medical decision-making to non-physicians.

"We have taken the physician out of the equation completely," she said, "and if [the non-physician] doesn't know the clinical pathway, they are winging it. It feels like a free-for-all."

Bernard added, however, that physician groups generally support PAs and NPs as "physician extenders" or "midlevels" who work under direct physician supervision or follow a written protocol.

At professional membership organization and state house levels, tension between physicians and NPs and PAs has existed for decades, although more so for NPs, who have fought harder and more successfully for independent practice rights. The Texas Medical Association, for example, helped kill numerous scope expansion bills during the last legislative session, including House Bill 4071, which would have enabled advanced practice registered nurses to practice independently.

Interviews with medical professionals suggest the experience in actual practice, however, is rarely contentious.

"The physicians we work with day in and day out are colleagues," said Susanne Phillips, a nursing professor at the University of California, Irvine. "It's what's right for the patient. It's what heals."

Geriatrician Dr. Todd James oversees a group of NPs who manage geriatric emergency patients at the University of California, San Francisco. "They bring immense value," he said, noting their skills in comprehensively assessing patients beyond their immediate complaint. "Geriatric medicine is holistic; many patient needs are not being met by the current systems, and NPs have filled the places physicians have not, cannot or do not want to fill."

How the roles originated and grew

The NP profession dates to 1965, when a nurse, Loretta C. Ford, partnered with a pediatrician, Henry K. Silver, to create the first academic program for NPs. Located at the University of Colorado, its aim was to meet the needs of underserved pediatric patients. The certificate program grew into a master's degree integrating nursing education, practice and research.

"At first, our scope was fairly limited to working with families, women and children," said Phillips, the UC Irvine nursing professor. "Our prescriptive authority was very limited in many states, focusing on conditions such as infection, and health promotion and disease prevention. The foremothers of our profession thought long and hard about how they could keep scope of practice flexible as the needs of the patients we cared for changed and grew."

The PA profession officially began the same year when Dr. Eugene A. Stead Jr. of Duke University put together the first class of PAs — four U.S. Navy hospital corpsmen with experience as medics. Stead acknowledged that he wasn't the first to consider the role. He knew of several physicians who were training their own assistants on the job.

One was Dr. Amos Johnson, a general practitioner in North Carolina who hired Henry Lee "Buddy" Treadwell as an office assistant and orderly and gradually taught him medical skills in the 1940s. According to a newspaper account cited by a Physician Assistant History Society article, Johnson testified in a case involving clinical training of non-doctors that Treadwell was so competent, he trusted him to take care of patients when he was out of town.

"The richest man in town would rather have Buddy sew him up than me because he can do it better than I can," he was quoted as saying.

The new advanced practice provider roles were well positioned to address another big development: The Medicare Act of 1965. The law that established Medicare and Medicaid drew large numbers of older and low-income patients into the health care system.

"Millions of people suddenly became eligible to access medical care," recounted Tricia Marriott, a PA and historian with the PA History Society. "Prior to that, patients paid out-of-pocket. Now we have all these Americans who have the capability to get medical care through an insurance plan [and] not a lot of physicians to go around."

Physician training programs had become standardized and harder to expand quickly, which created an opening for PAs and NPs, who could be trained and employed relatively quickly to meet the surge in demand.

Training requirements, school debt and salaries

While NP and PA jobs can be nearly identical, their educational requirements and paths differ. NP candidates must have a bachelor's in nursing science degree and have worked for several years as a registered nurse. Degree programs for NPs are one to two years (Master of Nursing Science) or three to six years (Doctor of Nursing Practice). To graduate, candidates must complete at least 500 hours of supervised clinical care.

PA candidates most often need a bachelor's degree with undergraduate coursework in the sciences, and most programs prefer students with prior medical or direct patient care experience, such as work as EMTs, paramedics or certified nursing assistants. Most PA programs last 27 months and include 2,000 hours of clinical rotations toward a Master of Physician Assistant Studies or Master of Health Sciences degree.

PAs and NPs may choose to do a residency to pursue specialist credentials, which can add significantly to clinical training hours.

Physician candidates, by comparison, must have a bachelor's degree, followed by four years in medical school, then three to seven years in residencies (depending on the discipline) supervised by other physicians. Clinical training time varies; according to the AMA, doctors with the highest level of education obtain up to 16,000 hours.

NPs and PAs are paid similarly, about $120,000 per year; physicians earn $208,000 on average, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The median debt of a medical school graduate is $200,000. For PAs, it's $105,000, and for NPs, $55,000, according to an analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics National Occupational Employment and Wage Survey data.

Visits to PAs and NPs are up, while visits to physicians are down

That PAs and NPs are being used more often to meet rising demand for health care is indisputable. A study published in September in the British Medical Journal found that between 2013 and 2019, the proportion of Medicare patient visits to NPs and PAs in the U.S. nearly doubled, from 14% to 26%, while visits to primary care physicians decreased by 18%. Eight out of 10 NPs and PAs work in primary care, which is where the physician shortage is most dire.

Advanced practice providers maintain that they are critical to meeting growing patient needs. Bernard, the physician wary of their proliferation, believes that their growing use is the result of corporate health care greed and government prioritizing access to care over patient safety and health care quality.

"Why would a company hire a physician if they can hire a non-physician for less money?" she asked. "We have a physician shortage. We need to stop looking for shortcuts and invest in creating fully trained physicians and incentivize them to choose types of medicine like primary care."

Research to determine whether the use of NPs and PAs puts patients at risk is almost nonexistent, and studies comparing quality of care among MDs, PAs and NPs give mixed results. Some research has found that physicians prescribe fewer unnecessary antibiotics for acute infections, order fewer diagnostic tests and make fewer specialist referrals for patients with diabetes, suggesting they provide more cost-effective care. A retrospective study of 30 million patient visits to community health centers found that PAs and NPs achieved equivalent or better results on a variety of quality metrics and cared for similar patient populations.

The debate over NPs and PAs is far from settled. But judging from human medicine's experience, Bottomley predicts that the road to acceptance of midlevel veterinary practitioners, if bumpy, will improve over time.

"It's been my experience in human medicine that health care systems looking for a more cost-effective method of delivering quality care have welcomed my students and graduates," he said. "It will take some veterinary professional associates to graduate and show what they can do and how important they can be to a team to be accepted."