Dr. Karen Fine draws national spotlight with bestselling memoir

Dr. Karen Fine

Photo by Nate Dziura

Dr. Karen Fine snuggles one of her dogs, Sesame. Fine became a veterinarian in 1992 at age 25. She takes a holistic approach to medicine and is certified in veterinary acupuncture.

After three decades as a veterinarian witnessing the connections between pets and their people, and a lifetime of building bonds with her own animals, Dr. Karen Fine put the experiences in writing.

The result is The Other Family Doctor: A Veterinarian Explores What Animals Can Teach Us About Love, Life, and Mortality, a book that drew national media attention even before it was released this spring. It became a bestseller shortly after.

In the memoir, Fine tells about how her gentle grandpa, a physician in South Africa, inspired her approach to healing. She recounts growing up in Massachusetts, where her first pet was a bright green parakeet named Taffy. She writes of going to veterinary school at Tufts University during a period when women were beginning to overtake men as the predominant gender in the profession and of overt sexism during that time. And she explores the grief people feel when their pets die, sharing the sickness and loss of her own beloved dog, Rana, and relating what it's like for veterinary teams to regularly beckon death through euthanasia.

Fine spoke with the VIN News Service about the whirlwind of her life since her book was published, telling stories behind the story. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I caught your interview on the National Public Radio program Fresh Air on March 13. That was one day before your book came out, and almost immediately after, you hit the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list.

Let's wallow in this for a moment. Because during that week, your memoir was on the same list as books by Bernie Sanders, and Michelle Obama, by Ron DeSantis, and Prince Harry. What does it take for a book to become a bestseller?

I don't know exactly, but I think it happened because of the Fresh Air interview. A producer at CNN heard the Fresh Air interview and wanted to have me on CNN. So I was on CNN for four minutes on the Saturday night the week the book came out. I think that's also why the book hit the New York Times bestseller list.

And I had no idea. I got a surprise phone call from my editor, and she was so excited. She told me, and then she said, "You can hear all these noises in the background; that's my phone and my computer dinging with everybody calling me and texting me and messaging me."

So it's a big deal for the team at the publisher, which was really exciting, too.

And you recorded your own audiobook.

I did.

That's exciting.

It was exciting. It was a little nerve-wracking because I was getting over a sinus infection. So I kept drinking tea with honey. And then, I guess it's pretty common, your voice sort of conks out after about three or four hours. I would keep trying. I wanted to go more, and then my voice would just, bleah.

It's very intensive when you're recording the book in the studio. You're sitting there in an enclosed studio with two doors for all this sound protection. I had headphones on, and there was someone in the studio helping me, and the Penguin Random House producer was Zooming in from Maine. It was really neat.

Had you anticipated any of this? What was your first inkling that it was going to snowball?

When it sold to Penguin Random House, that was a really great moment. And also when I got an agent. I ended up with a wonderful agent who sold the book to Penguin Random House.

I really felt like I was writing to what I felt was a need, because we see a lot of human suffering, not just animal suffering. I had something to say to people who were suffering, who were really bonded to their animals. If you're really bonded to your animals, you're going to end up suffering to some degree unless you have a species that lives a really long time. Most of our animals live 10, 15, maybe 20 years if we're really lucky.

As we discussed a little already, the attention begets attention. You are on CNN. And then the New York Times publishes an opinion piece by you about the guilt people experience when they end their pet's life. And then you're in Time magazine writing about puppy mills. Do you have time to practice medicine anymore?

The last few months have been pretty tough because I didn't really know what to expect. It's completely gratifying to see it take off like this. But then I'm trying to work. I took off the one week where the book came out. But other than that, I've been working in clinics about 20 hours a week.

I've done 15 or 20 podcasts and interviews and some in-person book talks. Just setting all those up and writing those articles as well was, yeah, it was a lot of work. And then doing edits for both the Time article and the New York Times article. And the New York Times article had over 800 comments before they closed the comment section, so just reading through those was very [time-consuming and] gratifying, too.

A lot of people were not so much even talking about the article but just saying, "Oh, I had an animal that died last year, and I really miss him, and it's been so difficult." Just sharing their stories. So it really seemed like it did hit a nerve for a lot of people.

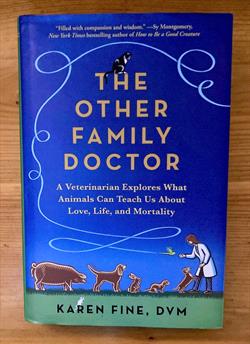

The Other Family Doctor

VIN News Service photo

Dr. Karen Fine's memoir was published in mid-March and appeared on the New York Times hardcover nonfiction bestseller list on April 2.

Take me back to your early days as a writer. You say in your book that you once thought of reading as a guilty pleasure. If reading is, then writing must be, too. But did you start out keeping a journal, or have you?

I didn't! I wish I had kept a journal. I did write a few things down. So if I was really upset about something, sometimes I would write a few pages about it. But I didn't have it as a regular practice, which would have made writing a memoir much easier.

It seemed like you did, though.

Once I started thinking about something, it was kind of surprising the memories that did come back. And just spending some time and putting yourself back in that situation and remembering where you were sitting or standing when you had a conversation with someone, even if you don't remember the exact words, you remember the gist of it.

For years, I had it in my head to write a memoir and to talk about euthanasia to help clients. What also really propelled me was [learning] about veterinary mental health and the issue with increased suicide risk in the profession.

That made me look at some of my experiences in a different light. I really examined my own experiences and thought, "OK, this was stressful. This was hard. I'm not alone in feeling that." I felt that I wanted to share the secret lives of veterinarians, and to talk about some of the stuff that we often don't talk about, even amongst ourselves.

A good bit of the book is about death and grieving: how you process the loss of your own pets; how you handle being the person who brings about death in your patients; and how you juggle the technical act of inducing euthanasia with providing comfort to your clients, which is a role I gather you don't learn in school.

Can I ask you to read a passage on this?

Sure.

Eventually, I grew accustomed to the process of ending a life through euthanasia. It was a bit like adjusting to performing surgery — how strange did it feel, initially, to have my hands (gloved, of course) inside the body of one of my patients? To see and feel their internal organs, to cut and sew tissue and skin? It took some getting used to. After a while, surgery was just another day at the office.

Euthanasia, however, is unique. For myself and, I imagine, most veterinarians, there will never be "just another euthanasia." Each one entails being fully present, as a sign of respect — for life, for death, for the individual being, for their human family. If the owner is not present for the procedure, I can focus all my attention on the animal. I am always conscious of the fact that my voice will be the last voice the animal hears, and my touch will be the last touch; I am aware that the veterinary assistant or technician holding the animal feels the same way. We don't speak about this, but it is always the case, no matter who I am working with.

If the animal's owner is present, I experience another dimension of awareness: I am hypersensitive to the person's emotional state. I know that the same act I perform to relieve an animal's pain can cause profound suffering on the part of their human family.

Part of the reason I adjusted to performing euthanasia was the patients themselves. Animals, I have come to believe, do not fear death as most people do. They try to avoid it, certainly. Like humans, they have a survival instinct, which can be fierce. Yet when I see animals in the process of dying, they seem to experience a calm acceptance. And by acceptance, I do not mean resignation; I mean recognition and acknowledgment. I mean a true, full comprehension of mortality.

The time surrounding death, for animals, is less of a cerebral experience and more of an intuitive, instinctual one. Many of the animals I euthanize are gravely ill and would likely die within a matter of days, or sometimes hours. These animals, I believe, know their death is near, and they are not afraid. The reason is this: They realize their body is breaking down. They know, as do other animals in the household, that they are dying. This is something they don't think about before their body is failing. But when it is actually happening, they can interpret and accept this knowledge. ... They make appropriate adjustments, such as hiding or not eating. They trust the intuition that has helped them all their lives as they receive messages from their physical body. ...

Among the near-death animals I have attended, I have occasionally sensed a reluctance to leave their people, and anxiety over my presence or about being in a hospital, but I have not seen what I would term "fear" as an animal is dying.

This may be why I don't personally fear death. ... I hope to avoid death for a long time, to live a long and happy and fulfilling life, and to die peacefully. When I am in the process of dying, my physical body breaking down, I may not want to leave it, but I also hope to recognize what is happening and to acknowledge the inevitable process on a deeper level, as I have seen so many animals do.

It's wonderful to hear the wisdom you've drawn from the passing of your patients and your own furry and feathery family members. But bearing witness to so much death and grief is still very hard. I'm reminded of a commentary that you wrote for the VIN News Service in 2019 titled Beyond wellness: admitting veterinary work is hard. Do you think the profession is getting any better at tending to its own emotional health?

I do think things are getting better. I'm an optimist. The focus for so long has been on wellness, and that was part of what I wrote about. I've since heard other things, which I didn't really think about myself, but as soon as I heard, I thought, "Well, that's really true." It's that, if you are depressed or anxious or if you're suffering, if you're having suicidal ideation, to hear the focus on wellness, like, 'Are you eating right and sleeping and exercising?' — and of course, if you're depressed, you may well not be — then that can also feel like it's your fault, and that you're not taking care of yourself.

The focus on wellness is a really good point and idea, but there's also got to be some understanding [that] it's not just about wellness. It's about recognizing how difficult this work is, that wellness is only part of the strategy. Are there mitigating strategies that we can take other than wellness to address how difficult this work is?

Part of it is just acknowledging that it's difficult. Even myself, for a long time, if I did think it was hard, then I thought, "Well, I'm stoic. I can do hard things." It was sort of a point of pride. And I think that that's the case for many, many veterinarians and veterinary staff.

But it's OK to say, for instance, "My animal was just euthanized, and I don't want to euthanize another animal or be in the room [right now]. Can someone else fill in for me?" That's something that's not often done in the profession. That's just one example of something that can maybe make people a little bit more comfortable.

I see what you're saying. So, it's not like, "My animal just died. I need to go work out, and I'll feel better and I can come back and do this."

Exactly!

I'm a person who tends to get very involved [with clients]. I once said to a therapist, "I felt enmeshed," and her facial expression was kind of horrified. She's like, "You shouldn't feel enmeshed with a client situation." And I thought, "Yeah, you know, I shouldn't."

So it's also about boundaries — not just boundaries about your time and your work-life balance but emotional boundaries. How much of yourself do you put into the work? When do you put [on] that boundary and say, "You know what, this is a really sad situation, but this is my role, and I'm not going to take on the emotions of other people."

Some of the most fascinating parts of the book I found to be your accounts of the sexism you experienced in veterinary school and early in your career. This is in the late 1980s and early 1990s. You're talking about being on the cusp of a great change in the profession going from predominantly men to predominantly women. What was it like to be part of that tidal shift?

My class was 70% women; it was the first class that had been more women than men. And for the most part, Tufts was great. Tufts never had a policy of not accepting women, but I know that other schools did. A close friend of mine who graduated 10 years before me was told, "You realize you're taking a spot away from a man."

When I graduated, there was a national conference in Boston that year. The demographics were just startling. People in their mid- to late 20s were more women, but over 35, it was over 90% male. It was stark.

What does it look like today when you go to a professional gathering?

I went to VMX in Florida. It's at a huge convention center, and they ended up turning some of the men's bathrooms into women's, or women's and men's. So that just goes to show you, right there.

Also in veterinary school, you talked about sharing faculty with medical students at Tufts, and when you attended physiology lectures together, the medical students had a tradition of behaving disrespectfully to their veterinary classmates.

We heard about this before it happened. What they did was, there were some medical students who sat in the last row and mooed. They made mooing sounds. When I heard about it in advance, I thought, "Oh, that's kind of funny." But in the class, you know, there we are, veterinary students, medical students. It seemed really disrespectful. Did they not realize that the physiology [among species] is so much the same? It's far more similar than different.

It was a strange introduction to, what do physicians think of veterinarians? It wasn't the best. Our anatomy labs were side by side, and we also used to peer into the doorways of each other's anatomy labs. They would say, "Eww, you do dogs?" and we'd say, "Eww, you do people?"

Unfortunately, I think the professional siloing of veterinary and human medicine hasn't changed a whole lot. Do you have some ideas for how One Health — the understanding that the welfare of people, other animals, and the environment are intertwined — how that could become something more than a nice-sounding concept but rather, something that's put into practice?

I think it would be great. There's a physician, a cardiologist named Barbara Natterson-Horowitz who wrote Zoobiquity, and she's led a conference, I think for a few years — I'm not sure if it's still going on, but that sounded like a really good way to bring physicians and veterinarians together [to discuss], what can we learn from each other?

For instance, there's a lot we can learn from physicians because many more studies are done on physicians and their attitudes and how they practice. They're a much bigger population.

But they might be able to learn from us in terms of — you hear a lot about physicians not wanting to talk about death and having trouble giving bad news. [This point was made] in Atul Gawande's book Being Mortal, that it's really hard [for them]. Instead of saying, "Well, you know, your third chemo protocol has failed; let's talk about going into palliative care [because] it's not likely protocol number four is gonna work," a lot of times, they don't say that. My sense is they go by what questions the patient asks, and if the patient asks that, they'll talk about it. But if the patient says, "What do we do now?" They'll say, "Well, here's protocol number four — this is what it involves."

Now, in veterinary medicine, partly for economic reasons, we're much more used to really giving as best of a prognosis as we can. A lot of times, we don't know the full story, but we're still saying, "Many animals with this blood work or this diagnosis only live for so long. Treating it may involve this, but the prognosis is still not good" — that sort of thing.

That's [a way] that we may be able to help physicians because we have to do that on a daily basis — cut to the chase.

Another topic that is common to both is the rise of telemedicine. You write that veterinary medicine is a tactile occupation and about the value of seeing your patients' home environments when you make house calls. And for yourself, you write of valuing having a doctor who physically touches you when you visit. What's your take on the rise of telemedicine?

I think telemedicine can be good. I wouldn't want to see it as a substitute for medicine in person, but it's interesting that telemedicine [enables you] to see into somebody's home, whereas you normally wouldn't.

You could say, "Show me your medications. Do you have them in a pill minder or something like that?" And if they say, "Oh, I don't know. One's in the cupboard here and one's over there," then you would start to wonder, are they able to give the medications whether it's to themselves or to the animal?

[On the other hand] if they say, "Oh, I have it right here," and there's a chart, then you know they're doing the best they can, and they're being pretty good about it.

I [remember] one telemedicine appointment for a house call patient early on in the pandemic. I had to renew a prescription, and it was the only way I could do that. The client had three dogs. One of them was very nervous, and when I came into the house — I was used to coming into her house — this dog was very, very anxious, even though he was on Prozac.

During the Zoom, the dog was playing and running around, and I was like, "Wow, that's how he acts! I've never gotten to see that before!" A lot of people are used to doing Zoom, so I think an animal is probably gonna act pretty normally when someone is Zooming with the health care practitioner. I thought that could be a really good potential in terms of, "Well, how do they act at home? Can we witness some of the behavior?" And of course, this animal is suitably medicated, so he was relaxed. But as soon as anyone comes over, it was a whole different story. I barely saw the dog. They had to kind of drag the dog into the room, and it was freaking out. That [difference] was really interesting.

I like that idea: It's not either/or; it's, yes, both.

Yeah, there are some benefits. Lately, too, a lot of times I'll have somebody send a picture of, like, a wound or a skin issue or an abrasion, especially if I've seen it and you want to know, how is it healing? Or if you're trying to decide, is this something where I can dispense some ointment or medication, or do they have to come in?

I'm guessing a lot of practices are doing that kind of thing because it's fairly easy. Everybody's got a camera now, and they can easily send a picture over. Something like that can be helpful for follow-up, as well.

Do you have concerns about establishing care through telemedicine though, where the veterinary-client-patient relationship is established not in person but remotely?

Oh, yeah. I have a hard time with that. Even when I treat animals holistically, that's not something I feel comfortable with. I think some veterinarians do, but I don't feel comfortable that there's an established veterinarian-client-patient relationship. I would need to see the animal even if I can't get near the animal, even if it's one of those animals you kind of got to look at from across the room, and maybe you're just giving a vaccine or an injection or just barely touching for a moment.

Maybe once a year, you could do that, and the other times you could do telemedicine potentially, depending on what the issue is.

Certainly, there's some things you really need to see in person, but considering the shortage of veterinarians, there may be some cases where maybe some rechecks could be done for certain things with telemedicine.

Now that you've earned something of a soapbox position, what's next?

Thank you for asking. One of my things is puppy mills and rescues, and also, all these breeds that are brachycephalic, with the pushed-in noses, like the French bulldogs are now the number one dog [in the United States]. Many of them need surgery to breathe comfortably, and I have a really hard time with that. And I love Frenchies! I think they're great. But I don't like seeing dogs that are bred that can't breathe comfortably. It's such a primary thing. So I feel like, what is our role as veterinarians? I would like to explore that. I feel like we do have some responsibility to our patients and to our clients to address that.

Also, I would like to teach narrative medicine [a topic on which she has written a textbook], and I do have something scheduled in November for the Colorado VMA [Veterinary Medical Association]. I would like to teach that material more.

And then my editor and my agent have also asked me, do I want to write another book? So I'm thinking about that, as well. I do really enjoy writing.