U.S. practitioners find many options among English-speaking countries

Photo by Dr. Ashleigh Fann

Dr. Ashleigh Fann contemplated this view at Ravenscraig Park while considering whether to leave her job in Texas to move to Scotland.

Before she knew it, Dr. Ashleigh Fann had walked nine miles. She’d strolled along the Fife Coastal Path, surveyed the Harbourmaster’s House, taken a gander at the beach and even prospected some local gyms. Finally, she took an hour-long respite at Ravenscraig Park. As she sat on a bench, enjoying her ideal of crisp, cool weather and gazing at the rugged Scottish terrain, a question churned in her mind: Should I move here?

Deciding whether to leave Dallas, Texas, and move 4,500 miles to Kirkcaldy, Scotland, for a job as a senior veterinarian at an emergency clinic meant facing a tide of uncertainties. Would it be a huge financial mistake? With the pay cut, could she afford the cost of living? How would she bring her dog? As an American, how often would she stick her foot in her mouth? Would taxes be a nightmare? Would she even like it there?

“I’m excited about the new possibilities and adventures,” Fann told the VIN News Service. “I’m also scared to death.”

As veterinarians who’ve left the U.S. to live abroad have discovered, all the research in the world can’t prepare you for everything, be it logistical snag, professional obstacle or plain ol’ homesickness.

They’ll also say that the reward outweighs the hardship. That the personal growth derived from untangling those challenges, embracing a new culture, and living and working in novel ways stays with them long after they return to America, if they ever do.

“I think everyone should live abroad,” said Dr. Kelly McGuire, who lived in Adelaide, South Australia, for more than four years. “It would help Americans broaden their perspective if they lived outside the U.S. for just a short time. There are American veterinarians all over the world. We can go so many places.”

American veterinarians are in a good position to find work in another country, though usually with the caveat of a salary reduction. The veterinary occupation appears on the skills-shortage list in several countries, and many regulatory bodies recognize schools accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Getting a work visa and license is often a matter of finding a job — employers typically have to make a case for hiring a foreigner and may provide a letter of sponsorship — then submitting a copious amount of documents plus fees, then waiting.

Whether heading to South Africa or the United Kingdom, in their 20s or 50s, solo or with families, veterinarian expatriates interviewed by the VIN News Service seem to share a common motto that fear is no reason not to try something new. There are other common threads: a thirst for adventure and a good dose of wanderlust, for a start.

That doesn’t mean they lack practical advice from learning lessons the hard way: Bulk up on savings to cover the moving costs and visa applications. Research details such as how to open a bank account, transfer money and get a cellphone plan — it can be harder than you’d think. If you have student loans, know how exchange rates could affect monthly payments. Be prepared for unrecognizable drug names and unfamiliar animal diseases. And yes, you will have to file taxes in two countries, although several provisions in the U.S. tax code help minimize double taxation.

Dr. Ashleigh Fann

Fann has dotted her i’s and crossed her t’s. Amid Army Reserve duty and working in Dallas in emergency practice and as a relief veterinarian, the idea of living in the United Kingdom has been simmering for years. In 2011, Fann attended a job fair and learned of a company that manages emergency veterinary practices in the U.K. Afterward, she periodically checked online for available positions but never pursued them. At the end of 2016, a friend in Scotland sent her a message: “Just do it already. Just rip the band-aid off.”

Fann took the friend’s advice. She saw a posting for a senior veterinary position and called the listed contact, who referred her to the district veterinarian. After a Skype interview, a job offer and a visit to the U.K. in March, things were falling into place. By April, Fann had researched her tax questions, ensured she could meet Army obligations by flying to Germany once a month, and received a sponsorship letter from her employer. By May, she had submitted her visa application and was awaiting approval.

Her tentative plan is to fly to Kirkcaldy in June to find housing, open a bank account and get a cellphone, then sell her Texas home to pack and ship belongings by July.

“I’ve tried to look at every angle I can think of,” Fann said. “I just want to make sure I know what I’m getting into before I jump in, knowing full well I have no control over anything, really.”

The job change means a significant pay reduction, but one of Fann’s motivations is finding a slower pace to life. Single with no kids, at 39 years old, she envisions traveling Europe, living simply, enjoying nature and continuing to practice the type of veterinary medicine she loves most. On an evening in March, she was researching Scottish hillwalking.

“We are so success-driven and money-driven that sometimes, we don't step back and realize that there is so much more to life than the size of your house or the type of car you drive,” Fann said. “Just get out and move about under your own locomotion, and see what the world has to offer, especially when it’s not covered in concrete.”

England

For the first time since she was 16, Dr. Amanda Guthrie doesn’t own a car. She walks to work each morning through The Regent’s Park, savoring the open green space within bustling London. By the time she arrives at the ZSL London Zoo, where she is a senior veterinary officer, she is eager to take on the day’s surprises.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Amanda Guthrie

Dr. Amanda Guthrie holds a Malayan tiger cub that was hand-reared at the Virginia Zoo after being rejected by its mother. Guthrie left Virginia last year to take a job at the ZSL London Zoo, where she encounters new and different exotic species of animal patients daily.

There are lots of them. In March, she examined a baby aye-aye, a bizarrely endearing lemur from Madagascar with spindly fingers. She saw Asiatic lions for the first time — there are just hundreds left in the wild. On any given day, she could work with bushbabies, pygmy hippos, tiny frogs, spiders, seahorses and giraffes.

“Anything and everything,” Guthrie said. “That is the fun part. Every day is different and you never know what is going to happen. It keeps you on your toes.”

Last year, at 37, Guthrie got her dream job working at one of the most historic, famous zoos in the world. She promptly moved from Norfolk, where she’d worked at the Virginia Zoo for five years, to London.

With an employer to sponsor her and qualifications in zoological medicine, getting her work visa and veterinary license was straightforward. Veterinarians must register, eventually via an in-person appointment, with the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, which recognizes AVMA-accredited schools. Once the required documents are submitted, including North American Veterinary Licensing Examination scores and a letter of good standing, processing takes 15 days.

Not to say it wasn’t expensive. Guthrie dished out more than $1,500 on fees, and visa applicants must prove they have a minimum savings balance and pay the health-care surcharge, which differs based on one’s circumstances. Moving to the U.K. also likely means taking a pay cut. According to the National Careers Service, U.K. veterinary surgeons make an average of £30,000 to £50,000 per year, equivalent to roughly $39,000 to $65,000.

In Guthrie’s eyes, the financial setbacks are well worth it. Her daily walks are emblematic of a newfound work-life balance that eluded her in the U.S. She’s embraced a minimalist lifestyle in a small apartment, taken advantage of London’s well-linked public transportation and explored the cultural scene.

“I feel that the quality of my life has improved dramatically,” she said. “My experience in the zoo business in America is pretty intense. I think you are always expected to sort of sacrifice. Here, when you are off, they really respect that.”

Used to being on call and responding to emergencies 365 days of the year, Guthrie’s 37-hour work week and roughly six weeks of vacation are blessings, and she feels her employers have more regard for her personal life. She’s kicked the old habit of checking work emails at home and observed that few things truly warrant an emergency call.

“I feel more laid-back at work, less stressed, less urgent,” she said. “There’s less to get upset about or worked up about on a day-to-day basis.”

One aspect of London life, at least at first, was an exception. “Banking and paying for stuff is an absolute nightmare,” Guthrie said.

U.S. credit history doesn’t follow expats — without Guthrie’s credit, landing her flat involved a massive deposit. Meanwhile, opening a bank account can be notoriously difficult, sometimes requiring a series of documents that newcomers won’t likely have. For Guthrie, the process took more than six bank visits that sometimes left her in tears in the lobby.

And Guthrie didn’t manage to escape politics by emigrating. Brexit has sweeping implications for the U.K. veterinary profession, given the number of foreign veterinarians from the European Union and international agreements. Like other veterinarians, Guthrie is waiting to see how negotiations might affect her work, such as the ability to transfer animals or send specimens to labs in other countries.

Beyond banking, Brexit and adjusting to Celsius, military time and strange blood-work units, Guthrie is hard-pressed to find something about London life she doesn’t like. She even gets to maintain her “Doctor” title, which has been allowed in the U.K. since only March 2015.

“I can’t predict the future, but I could see myself being here a long time,” Guthrie said. “There is so much opportunity for me to grow and contribute to something really significant. This is the place I’ve dreamed of being.”

South Africa

Dr. Suzanne Richcreek was a bit of a celebrity when she finally went to the hospital with blunt force trauma and a broken rib. Most people don’t survive Cape Buffalo attacks.

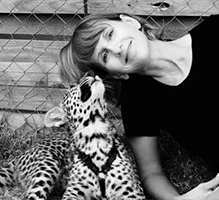

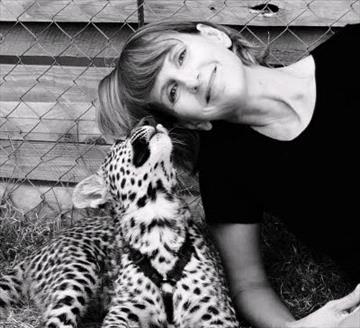

Photo by John Loehr

Dr. Suzanne Richcreek visits with a 4-month-old leopard at an animal sanctuary in Bloemfontein called Cheetah Experience, where she and her husband volunteered before moving to Cape Town.

With their formidable w-shaped horns and weight of up to 1,900 pounds, the fact that they are herbivores was no consolation when one slammed into her chest as it made a panicked escape from a boma — a livestock enclosure — at a wildlife veterinary training in South Africa. She’d curse the person who left the door ajar, but she wears the scar on her chest with pride.

Richcreek undoubtedly has accomplished her goal of “messing life up a bit.” At 54, after 17 years of running a feline-only clinic in Minneapolis, she wanted a new adventure. Her husband did, too. Avid travelers, they’d vacationed in South Africa before, where Richcreek had volunteered with a cheetah conservation organization. In January 2015, she sold her practice. By June, they were in Cape Town with four bags each.

“All of a sudden, I’m lying in this bedroom in South Africa with all our stuff surrounding me, and I’m like, ‘What did I do?’ ” she said.

As far as living a bold life, Richcreek is happy with the decision. Richcreek’s dream that she would find work as a big-cat veterinarian, however, has clashed with a harsh reality. She arrived before finding an employer, and nearly two years after the big move, still has not obtained a license to practice.

“There are some real lessons I’ve learned,” she said. “It’s not National Geographic, it’s not 'Animal Planet.' There are major obstacles here. I’ve had a lot of doors slammed in my face, and I’m relatively persistent.”

The obstacles she encountered include an onerous registration process, a dearth of jobs she’d hoped for and a professional community less welcoming than anticipated.

The veterinary occupation falls on the skills-shortage list in South Africa, which allows veterinarians to apply for a special work visa without a prearranged employer. That sounds great on paper, but to get it, applicants must have qualifications evaluated by the South African Qualifications Authority and register with the South African Veterinary Council. Kelly Manne, a senior consultant at Intergate Immigration Service, said registering is a complex process that can take more than a year.

Richcreek would be able to work legally with employer sponsorship, but has been unable to find an employer willing to endure the paperwork needed. And she learned the hard way that without employer sponsorship, anyone who did not graduate from the University of Pretoria or the Medical University of South Africa must pass a council registration examination held only once a year, in October. She graduated from veterinary school in 1993, and the idea of drumming up skills she hasn’t used for decades, not to mention familiarizing herself with myriad exotic diseases and poisonous plants, seems insufferable. She tried to find a way around it to no avail, then begrudgingly accepted that she would have to take the exam if she wanted to practice.

“I hated South Africa that day,” she said.

Her advice to veterinarians with their sights abroad is: “Get the information straight as to what you have to do to practice … understand the rules much more than I did.”

There’s also a steep pay disparity: Richcreek has come across relief work that pays $10 hourly; PayScale, a salary comparison website, puts the median salary at roughly ZAR 471,000, or $36,000. Then again, South Africa has been listed as the world’s cheapest country to live or retire.

Richcreek is resilient. She plans to take things one step at a time, acknowledge that her ideal job might not materialize and hunker down to study for exams. Despite the wrenches in the works, she doesn’t regret the move.

“I wanted to get out of my comfort zone, because I felt if I didn’t, I’d be stuck in a rut,” she said. “My husband says when we’re old and sitting in rocking chairs, we’ll be happy to say we did this. You gotta live your life.”

For now, Richcreek is living in the country on a retirement visa, which requires only proof of minimum income. The weather is phenomenal, the mountains are picturesque, wineries abound and Kruger National Park, overflowing with the animals that Richcreek loves the most, is a two-hour flight away. The lifestyle is relaxed. Sometimes too relaxed — a recent trip to Johannesburg left Richcreek on a stalled train for seven hours.

“You learn to go with the flow more and not get stressed out, because there is nothing you can do,” she said. “The train is going to go when the train is going to go.”

Richcreek recalls a moment in 2014, before moving, during a visit with the owners of an animal sanctuary in South Africa. Her husband was walking down the road with a large dog on his left, a glass of wine in his hand, and a cheetah on his right when he said, “I could live here.”

Ireland

Veterinary practice sometimes comes with whiskey-drinking in Ireland. Dr. Anne Whipple was too polite to refuse the offer of an 11 a.m. round during one of her many farm visits as a veterinary nurse, and her memories of that day are bittersweet. On one hand, it didn’t lead to a particularly good day — she spent the remainder feeling ill while assisting the lead veterinarian with cattle tuberculosis-testing in a freezing rain. On the other, the hospitality represents what she found so wonderful about working in Ireland: a certain sense of hearty community.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Anne Whipple

With her dog, Marley, Dr. Anne Whipple takes in the scenery after a hike to the top of Slievenamon in County Tipperary.

“I felt like I always knew someone, regardless of where in the country I was working,” Whipple said.

Mixed practice in Ireland involved lots of all-day farm visits, which often ended with tamer invitations to tea or dinner. Whipple grew familiar with the rural farmers and learned about the countryside, and she found the veterinary community itself warm and friendly.

Perhaps it was the novelty of being a lone American woman in a rural town, but even when Whipple first moved to Ireland after her undergraduate studies in Minnesota in 2003, everyone was kind and seemed to know who she was even before she knew them. She joined local sports teams and had an instant network of friends.

Whipple’s life after receiving her bachelor’s in Spanish reads a bit like a travel novel. A far cry from having a five-year plan, she acquired a short-term student work visa and booked a ticket to Ireland to satisfy a travel craving, worked on a stud farm with accommodations in a tower house — think Downton Abbey but far less grand — dated an Irishman and wandered castles.

She stayed long enough to become an Irish citizen, meet her husband while playing hockey, and discover and pursue her career.

“My original plan of action was just to cover my travel expenses,” Whipple said. “The fact that I stayed long enough to become interested in veterinary medicine, get accepted to college and qualify as a veterinarian was certainly a bonus.”

Whipple attended University College Dublin and was able to get U.S. government loans because the college is AVMA-accredited. As an Irish citizen, she paid lower tuition rates and graduated with a relatively manageable debt of roughly $20,000. Because she developed her career in Ireland, Whipple sidestepped some processes expats might face, such as finding an employer to sponsor a work visa. All veterinarians must register with the Veterinary Council of Ireland.

Whipple now lives in Canada — her husband is Canadian and they had planned on moving since before Whipple finished veterinary school — and has never actually practiced in the U.S. But she imagines that there are aspects of Irish life that wouldn't appeal to some Americans. Salaries certainly are lower, at a median of roughly €39,000, or $43,500, according to PayScale. It’s hard to find small animal-only practices outside of urban areas such as Dublin, Cork and Galway. The school system is heavily influenced by Catholicism, real estate is expensive and if gloomy weather gets the better of you, you might not like the way dampness seeps into your bones on a winter’s day.

Whipple never let gray skies stop her. She loved the freedom to explore the land, spending hours traversing Ireland’s green, scenic paths with her dog by her side. By the time she left, she’d lived in an old stone church, a manor estate, a stone-barn-turned-apartment and a hilltop house overlooking a valley.

It may have been a surge of youthful spontaneity and slight naiveté that initially brought Whipple to Ireland, but what made her stay was much more.

“I felt this is home almost as soon as I arrived,” she said.

Canada

The day after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, a friend posted “Well-played” on Dr. Corinna Kashuba’s Facebook page. Just months earlier, Kashuba and her family had moved from Illinois to the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

Northern Illinois University photo

Dr. Corinna Kashuba

In the tumultuous lead-up to Donald Trump’s election, the internet was saturated with move-to-Canada memes. On election night, Canada’s immigration website crashed amid a sudden flood of visitors.

Kashuba’s move was not for political reasons, but the timing is not lost on her. Regardless of your side of the aisle, Kashuba finds things in Saskatchewan quite moderate, even with midwestern Canada’s reputation for edging conservative. She continues to follow American politics, staying mindful of how recent changes might affect friends and family.

Kashuba doesn’t like to criticize either country, because the reality is that for her, both feel like home. Hailing from Alberta, Kashuba followed a professional path in veterinary academia from Canada through the U.S. and back again.

“I really love each country equally,” she said. “When you move to a different country and it grows on you and you eventually love it, it doesn’t mean you love your old country less. It is good for people to live internationally at least for a small amount of time, to get the feeling that there is more than one way to live and that ‘the best way’ is often subjective and depends on your priorities and life circumstances.”

Kashuba did her undergraduate studies at the University of Alberta, conducted research and received her DVM at the University of Illinois, went back to Canada for a year to work for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, headed to the University of Missouri for a residency and Ph.D, and raised her kids in Maryland. Most recently, she and her husband had positions at Northern Illinois University, he as a math professor, she as attending veterinarian and director of research compliance, integrity and safety.

After 15 years in the U.S., they decided to apply for positions at the University of Saskatchewan, searching for a better academic fit and wanting to be closer to Kashuba’s family. Both received offers, packed up their lives, and moved to an acreage outside Saskatoon.

Ultimately, Kashuba said, she’s found transitioning from country to country fairly smooth. Besides colder winters, lower population density and more environmentally-aware consumers, she said, life just isn’t that different.

“It’s been very easy to come back to this country,” she said. “We fell into a rhythm quickly here.”

With prearranged employment in Canada, U.S. veterinarians can get work permits thanks to the North American Free Trade Agreement, and getting a license to practice is easy for most who have graduated from an AVMA-accredited school. Veterinarians must apply for a Certificate of Qualification from the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association’s Medical Examining Board, then register with the licensing body in their province. Each province has slightly different requirements — Kashuba had to attend a weekend seminar to learn regulations specific to Saskatchewan.

“Your experience can vary depending on the province you are in, but the standards are equally high,” Kashuba said. “You can have variation as to specific regulations or species, but really the two countries are very similar, so that it isn’t a great shock to anyone’s system if they make the big move.”

The Government of Canada website offers a primer on preparing for life in Canada, which includes information on cost of living, taxes, language and more. Veterinary salaries in Canada, though still lower than the U.S., are more comparable than in most other countries. According to Canada’s Job Bank, the median salary is $81,640 Canadian ($60,278 U.S. at the current exchange rate), while the median in the U.S. is $88,770, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For Kashuba, health care has made for the biggest logistical challenge, regardless of which country she’s moved to. Accustomed to universal coverage, maneuvering the U.S. insurance system was jarring at first. So was seeing advertisements for hospitals.

“‘Come have your baby here! Come here for your cancer treatment!’ … that’s not something you see [in Canada],” she said.

On the other hand, being in Canada sometimes means longer wait times and fewer provider options. And this time, she’s moving with a full family. With four sons, life is frenzied no matter where she lives.

“It was easier to adjust when it was just me,” she said. “Now, everything takes more time. But it’s quite doable, and you just set your mind to it, do your homework, and find the right people to help you along.”

Adelaide, Australia

When Dr. Kelly McGuire got the green light to remove a 10-pound splenic tumor from a 90-pound dog at her clinic in Denver, she didn’t bat an eye.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Kelly McGuire

A 5-year-old ringtail possum named Fizgig visits Dr. Kelly McGuire for a wellness check at a clinic in Adelaide.

“That’s something that before I went to Australia, I would’ve been in tears,” McGuire said.

Working for more than four years in Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, armed McGuire with grit and self-confidence. Sure, it’s a large city of 1.3 million, but it’s remote. When there’s no specialist to refer to and the nearest emergency clinic is an hour away, you’re on your own.

“I had to learn to accept what was in front of me,” she said.

That included tasks that were never expected of her before, such as bagging bodies, intubating patients and cleaning instruments. In a day involving more than 30 patients, she’d have perhaps one fellow veterinarian and a few helpers on deck. It was high-volume and high-independence. It also gave her the opportunity to perform surgeries that she might have never encountered in the U.S.

McGuire moved from Colorado to Adelaide in 2012 after applying to a job on a whim. When she called her mom to deliver the news, her mom asked if she was pregnant. “No,” she responded. “I’m moving to Australia.” Five weeks later, she was on another continent.

“It was probably a bit crazy,” she said. “But part of my philosophy is not to say no to things just because you might be scared.”

Veterinarians are in high demand in Australia and are on its skills shortage list, which allows them to apply for a skilled migrant visa even without employer sponsorship. Veterinarians who graduated from AVMA-accredited universities can register directly with the veterinary board specific to their Australian state, many of which allow veterinarians to register from overseas. If the veterinarian’s specific visa type requires a skills assessment, they must apply for one with the Australasian Veterinary Boards Council (AVBC).

Dr. Stefan Tulloch, AVBC accreditation officer, said he is surprised more U.S. veterinarians don’t practice in Australia, but has heard it’s related to the low pay.

McGuire can attest to that. For her, the move was a financial blow that she was in some ways unprepared for. The average veterinarian salary in Australia is the equivalent of around $56,000 U.S., according to Open Universities Australia. The heavier burden, however, was that with remaining U.S. student debt, the exchange rate against the stronger U.S. dollar meant a much higher portion of Guthrie’s income went toward monthly payments.

“Look into the financials and understand the legalities of what’s required of you,” she said. “It can financially ruin you if you don’t pay attention to the details.”

McGuire’s recent return to Denver was largely to focus on paying off her loans and finding some financial stability. She said if she had known how much it would set her back financially, she might have chosen not to go. She’s grateful she didn’t know — returning to the U.S. with a husband, child and newfound professional confidence was priceless.

The 3,000-mile Australian road trip, the scuba diving course in Sydney, and the kangaroos and koalas gracing the yard weren’t so bad either.

As for the dog in Denver with the tumor? It made a full recovery.

Sydney, Australia

Dr. Mara Hickey misses squirrels. Buying huge bottles of acetaminophen at the pharmacy. Combos baked snacks. Having colleagues know who a Wonder Twin is. Good lemonade and snickerdoodles.

Photo courtesy of Dr. Mara Hickey

An ill koala gets attention from Dr. Mara Hickey at the University Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Sydney.

But she loves living where “no worries” is the right response to nearly everything. Where pedestrian signals tell you aloud it's safe to go and people thank the bus driver as they exit. Where ravens cackle overhead, and where pavlova and sausage sizzles can be eaten with great regularity.

Like many expats, Hickey finds there’s a certain kind of split that comes with leaving home.

Hickey moved with her partner and two children to Sydney from Los Angeles, drawn to the combination of an excellent position in academia and the urban life she’s always loved. It was harder, it seemed, to find that combination in the U.S., where many of the academic positions were in small college towns. With a partner who’d spent years living overseas, turning her sights abroad was instinctual.

Moving overseas solo is one thing. Moving with a family of four and three pets is another. It took six months of planning. Though her employer, who sponsored her skilled work visa, reimbursed her for some expenses, she was $10,000 deep by the time she’d covered visas, airfare, pet shipping and quarantine, health insurance, household goods and basic furnishings.

Once they arrived, there were some growing pains. Snagging a rental home was brutal, and rent is paid by the week. Health insurance has been tricky. And her partner couldn’t find a job for the first nine months.

But Hickey is now doing the kind of work she’s always wanted at the University of Sydney veterinary teaching hospital in emergency and critical care, lecturing and overseeing the students that rotate through her service. As a specialist, she enjoys a salary comparable to what she made in the U.S.

She sometimes moves through life without even realizing she’s in a new country — that is, until one of the idiosyncrasies of Australian speech crop up, for example, the tendency to use diminutive nicknames such as “tradie” for tradesman and “sparkie” for electrician.

“It’s pretty common for me to just go about my day, with nothing seeming weird, and then someone says something that completely throws me for a loop,” Hickey said.

Same goes for when she holds a koala, examines a Kingfisher, searches for a baby in the pouch of a ringtail possum, or sees a patient with a brown-snake bite or tick paralysis. Sometimes, she catches the ferry, and as the boat drifts past the iconic Sydney Opera House, she thinks with a thrill, I’m really living in Sydney.

Like Los Angeles, Sydney is big-city life. Hickey could try a different restaurant each night and select from an endless supply of live music. As she takes advantage of the city’s vibrancy, she occasionally is thwarted by bouts of homesickness, preoccupation with the U.S. political scene or concerns for her parents’ health back home.

“I really, really like Australia,” she summed up. “And really, really, miss a lot from the U.S.”