Canine-flu-map

Screenshot of Tableau map

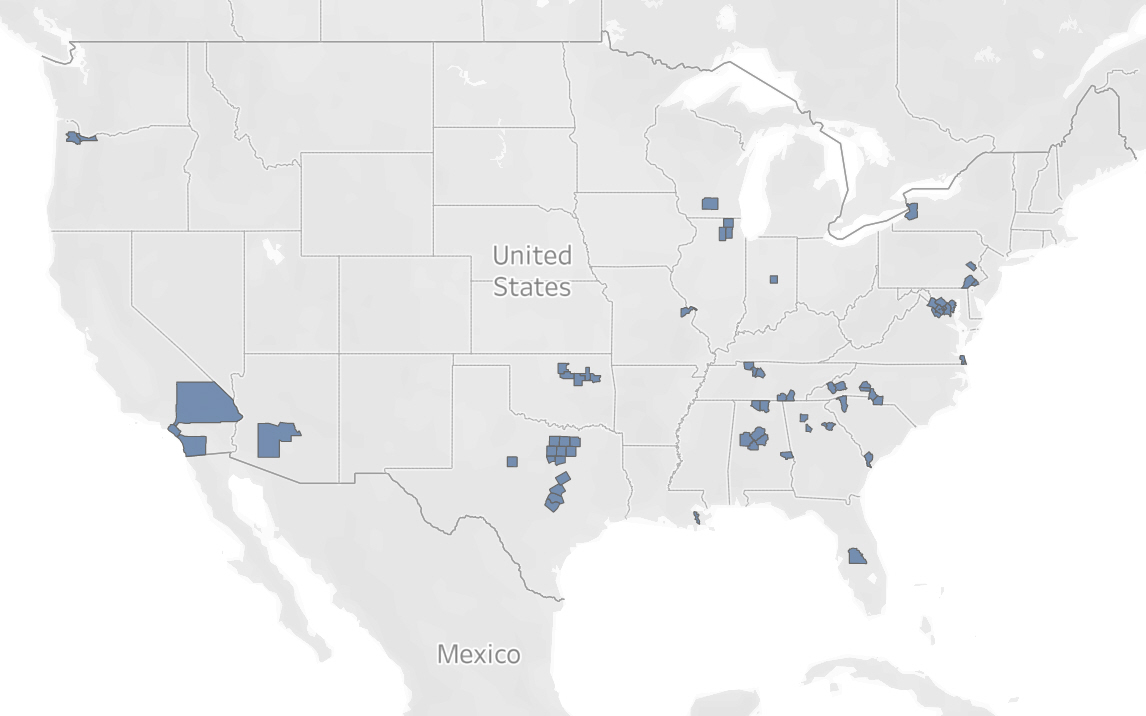

Filling an information gap in veterinary medicine, an infectious diseases expert in Canada has begun mapping cases of canine influenza in North America. The latest map, above, shows the locations of reports submitted by veterinarians and identified through research since August through Jan. 11.

Click to view interactive map.

Canine influenza has been hopscotching around the country of late. Since December, the highly transmissible respiratory disease has been confirmed in dogs in Alabama, Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and possibly other states.

Keeping track of infections that crop up hither and yon can be challenging. Neither the United States nor Canada has an active surveillance system for canine flu.

To address the data vacuum, Dr. J. Scott Weese, an infectious diseases veterinarian at the University of Guelph's Ontario Veterinary College, launched in December a one-man mapping initiative.

Weese invites veterinarians to report any laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of canine influenza or case of acute respiratory disease in a dog that has had direct contact with a laboratory-confirmed case. He collates reports in an interactive map.

The map "is useful for talking to clients and facilities (for example, day cares) about risk and mitigation (such as vaccination)," Weese said in an email to the VIN News Service. "It also helps us know the degree of clinic risk that can be present, since flu can be spread in vet clinics."

Canine flu is caused by influenza viruses known to infect dogs but not humans. There are two recognized strains. The first, known as H3N8, originated in horses and was first detected in the U.S. among Florida greyhounds in 2004.

Most recent cases in the U.S. have been caused by a second strain, H3N2, which sparked a large domestic outbreak in 2015. Evolved from an avian influenza virus in southeast Asia, H3N2 has been repeatedly carried into North America, primarily from dogs rescued from the meat trade.

After the 2015 outbreak, canine flu became sporadic. Once that happened, Dr. Steve Valeika, a veterinarian and epidemiologist in North Carolina, said he stopped routinely recommending the flu vaccine. "However, I always lamented not having real-time info about whether cases were reported close by," he said. "If it continues to be sporadic, a good mapping system can help guide vaccination recommendations."

The virus can cause signs in dogs similar to those in people, including coughing, which generally is mild. In severe cases, dogs might become feverish, short of breath and cough up blood — signs of hemorrhagic pneumonia.

Mortality rates are estimated to be around 2%, with deaths most often reported in older dogs or dogs with underlying diseases.

Vaccines can help prevent severe illness but do not prevent a dog from becoming infected or shedding the virus.

Mapping canine flu

About 200 veterinarians have reported cases to Weese so far. "We're getting a good idea of how widely it's spread and how patchy it is," he said, "consistent with a virus that jumps around as dogs move and can come out [of] nowhere to cause problems in a new area."

Unlike human flu, the canine version isn't seasonal. "Human flu is endemic, and flu seasons occur largely because of changes in human behavior," Weese said, such as more time spent inside and in close proximity with others. "Canine flu is sporadic, and the dog-contact changes over the year are different."

He said he'd expect a canine "flu season" to be associated with times that dogs travel more and spread the virus to new areas, and when they have more dog-to-dog contacts.

Weese focuses his data collection effort on gathering reports from veterinarians so he can be sure they are actual flu cases.

"Sometimes people say their dog has flu when it really just has an undiagnosed respiratory disease," he said. "I get some reports from the public, but those usually go into a ‘suspected' list, or I get more details."

Weese is not the first to take up the surveillance challenge.

When H3N2 began circulating in the U.S. in 2015, Dr. Amy Glaser at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine's Animal Health Diagnostic Center attempted to establish a voluntary reporting system, according to Edward Dubovi, a professor emeritus at the center.

"Reports from diagnostic labs were displayed by state so that vets could determine if a confirmed case of canine influenza virus was reported in their state. As this was voluntary, not all states' labs participated, but Idexx did," Dubovi said, referring to one of the world's largest private veterinary diagnostic laboratories. "This was important, as they did testing for vets in all states."

Dobovi said that when Glaser retired in 2019 and the number of canine flu cases was low, "the effort lost its champion." When he, too, retired soon after and Covid-19 hit the world, "all interest in this program disappeared," he added.

Dubovi described Weese's mapping project as a "laudable effort" and an improvement over "Google reports, where cases may not be verified as flu."

Meanwhile, factors that might lead to the creation of a more rigorous national reporting framework are probably not to be wished for. Dubovi said that sort of response could happen if "the virus becomes more virulent with high mortalities, or canine flu starts to infect owners."