Practitioner approaches vary, as cause and nature of toxicity to dogs remain mysterious

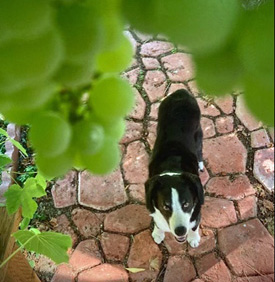

Finn and grapes

VIN News Service photo

Sensitivities to grapes vary in dogs, but it's best to keep the fruit out of their reach.

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Weighing an impressive 130 pounds, Romulus the Rottweiler appeared to be well-fed by his owner, a pizza parlor proprietor in Roanoke Island, North Carolina. But sometime in 2015, the 10-month-old dog went off his food, rapidly shedding about 20 pounds.

Romulus' veterinarian, Dr. Mark Grossman, quickly discovered the problem. The dog had severe kidney disease, though Grossman could only guess at the cause, musing whether it might be hereditary. Then, after treating Romulus for a couple of days without much success, a clue: The owner said he had been giving Romulus grapes.

"He said some days he would give none, and some days he would give as many as five or six grapes," Grossman said. "It was a casual thing for him."

Even after being sent to a specialist, poor Romulus had to be euthanized. No necropsy was performed, and the cause of the patient's kidney disease remains uncertain. Still, Grossman suspects that Romulus' demise might be one of the relatively small number of cases of dog death by grape.

That grapes, or Vitis fruits, and their dehydrated forms such as raisins, are toxic to dogs has been an accepted fact in the veterinary realm since 2001, when a letter published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association by veterinarians at the Animal Poison Control Center of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals alerted practitioners to their toxicity. A host of scientific studies have reinforced the link between grapes and clinical signs in dogs (and some cats) that range from lethargy and vomiting to acute kidney injury.

Still, what causes grapes to be toxic to some animals and why some individuals are more sensitive to them than others remains one of veterinary medicine's great mysteries.

A potential breakthrough came last year, when veterinarians from the ASPCA and two veterinary hospitals in the United States identified tartaric acid and its salt, potassium bitartrate (also known as cream of tartar), as the possible culprit. The link, while promising in theory, hasn't been definitively proven. As for treatment guidance, the ASPCA indicates that the higher the dose, the higher the risk.

"The amount actually ingested is critical in determining treatment — any more than one grape or raisin per 10 pounds of body weight is potentially dangerous," Dr. Colette Wegenast, a toxicologist at the ASPCA, told the VIN News Service by email.

She continued: "For now, it is challenging to determine which grape and raisin exposures may lead to acute kidney injury. The toxic component is speculated to be tartaric acid, and the content in grapes and raisins varies, leading to variable toxicity. More than one grape or raisin per 10 pounds of body weight may pose a risk for renal effects."

The lingering knowledge gaps are leading practitioners to take different approaches to how often, and how intensively, they treat cases of suspected grape poisoning, judging from the results of an online poll conducted this month by the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News. The poll drew responses from 2,899 veterinarians.

The majority indicated taking a relatively cautious approach: When asked about their level of concern when dogs eat grapes, 23% selected "High - I throw my body between them and a single grape or raisin," and 51% selected "Moderate - I recommend an exam/bloodwork with known ingestion."

At the same time, one out of five respondents seem more relaxed, with 15% selecting "Low - I worry only if they consumed a large number (more than 0.32 ounces/kilogram)" and 8% selecting "Very low - I don't worry if my dog grabs the occasional grape or raisin."

Staying on the safe side

Although the reason grapes are toxic to pets remains unclear, a fair amount of research has been directed at the general subject. Studies suggest that severe illness and death from grape ingestion are uncommon, especially in cases involving large dogs that ate only one or two grapes. Five scientific papers published since 2015 give survival rates following suspected grape ingestion ranging from 92% to 100%.

In the latest paper, published in June, researchers in Holland studied the outcome of grape ingestion in 95 dogs and 13 cats, based on cases reported to the Dutch Poison Control Center and follow-up interviews with veterinarians. Of the 108 animals, 15% (14 dogs and two cats) developed clinical signs that included vomiting, lethargy, diarrhea, anorexia, tremors and restlessness. Just one, a dog, developed acute kidney injury — and it survived. Many of the animals had been treated with induced vomiting or activated charcoal, potentially preventing kidney damage.

Looking at previous studies, the Dutch researchers found that since 2005, incidences of grape-induced acute kidney injury in dogs had ranged widely, from 0.17% to 32.6% of ingestion cases, though they noted that multiple factors made it difficult to compare study findings. Patient records, for instance, were obtained from different data sources and the criteria for diagnosis of kidney injury differed from study to study. Moreover, even when excluding patients with a history of suspected or known renal disease, the potential for other factors to have contributed to kidney problems (such as administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) would be difficult to rule out.

The Dutch researchers also postulate that the proportion of dogs suffering from severe side effects may have declined in the more recent studies because increasing public awareness of grape toxicity has prompted more pet owners to seek guidance — even in instances where one grape was consumed. Indeed, Wegenast at the ASPCA said its poison control center in 2021 handled around 16,000 reported exposures to grapes, raisins, grape and raisin derivatives, and tartaric acid, up almost threefold from around 5,600 in 2017.

Although most veterinarians would agree that a massive dose of a toxicant in a tiny animal likely would present greater risk, no definitive dose–response relationship appears to occur with grapes, the Dutch paper notes. Such ambiguity demands a degree of caution, posits Dr. Andrew Mackin, an internist based at Mississippi State University.

"The difficulty is when to decide to turn caution off — and the answer is, we just don't know what the safe level of grapes is for individual dogs," Mackin said in an interview.

Mackin accepts that determining the exact cause of death isn't always easy, especially when assessing anecdotal cases based on retrospective data. "There are at least two cases that I'm aware of where small to midsized animals have been reported by veterinarians to have kidney failure after eating one grape," he said. "And the attitude from folks that don't believe that's possible is that there was probably something else going on. They could possibly be right."

For his part, Mackin suspects that some dogs have an idiosyncratic sensitivity to something in grapes, similar to how a minority of humans and other animals react poorly to certain drugs. He offers carprofen, an NSAID, and azathioprine, an immunosuppressant, as examples: The drugs can cause liver damage in small numbers of canine patients.

"Just like with drugs, some foods might be safe for most dogs, but not safe in all dogs," Mackin said. "And if you have that conversation with the owner, informing them of those risks, it gives them a choice on whether to treat the animal based on their level of concern and their budget."

'Cover-your-ass' veterinary medicine?

Mackin was among veterinarians who contributed in 2019 to a lively discussion on the message boards of VIN about grape toxicity that attracted 128 posts. Some who chimed in recommended that veterinarians take a slightly less cautious approach. One was Dr. Pete Wedderburn, who practices in Bray, Ireland.

"To me, the typical response with grapes can veer towards what has been called cover-your-ass veterinary medicine," Wedderburn said in an interview. "You do absolutely everything possible so that you can't be found wanting at a later stage."

Wedderburn agrees with Mackin that owners should be informed of the risks before considering whether to pursue treatments. But he would like to see veterinarians make more forthright recommendations and, in instances where a large dog has eaten a single grape, he'd recommend they sit tight.

"I would give an opinion that the risk is so low that it would be very unlikely that it's going to cause a problem, and that they therefore don't need to do anything," he said. "But that doesn't mean I'm dismissing the risk as impossible."

A potentially negative consequence of too readily recommending treatment, Wedderburn fears, is that veterinarians could be accused of overstating risks to generate more business. "One of my big concerns is public skepticism about vets," he said. "And I think when we're seen to recommend treatments that are going to cost several hundred pounds — and when the rationale for that treatment is debatable or worthy of being questioned — it lays us open to that accusation." (The pound is currently worth US$1.16).

Being honest with clients, he adds, also could entail informing them of the risks, albeit small, associated with treating grape poisoning. Induced vomiting, for instance, can in rare instances cause aspiration pneumonia, where gastric contents and other substances get into the lungs. Undergoing treatment also could cause an animal stress overload; for instance, putting pressure on an older dog's heart.

Others agree that treatment risks shouldn't be discounted, including Grossman, who also is a VIN toxicology consultant and a former coordinator of the Georgia Animal Poison Information Center.

"The damn dog's probably got a better chance of dying from a car crash from the owner coming to the clinic than from eating a couple of grapes," said Grossman, who, despite his experiences with Romulus, also takes a more relaxed approach to applying treatment — in more obvious low-risk circumstances.

Should he be confronted with another 130-pound Rottweiler — one that, unlike Romulus, had eaten but a single grape — he quipped: "I would probably tell the owner that maybe the chances that it develops kidney disease would be about the same as me waking up tomorrow 35 years old. I mean, c'mon now. We can't go crazy over this stuff. I mean, if a 130-pound Rottie ate one ibuprofen, we're not going to bring him in and treat him for kidney disease and gastric ulceration."

Similarly, Grossman said he wouldn't treat a large dog that had eaten a single chocolate-chip cookie. (Much more is known about the toxicity of chocolate to dogs, enough that VIN has developed a toxicity calculator based on amount and type of chocolate consumed.)

Mackin, who is a little more cautious, acknowledges that there are risks associated with treating dogs, though he maintains they are low compared with treatments for many other conditions. "[A]t least for grape toxicity, the treatment is pretty safe; it's just expensive, so I think it's a reasonable thing to have the conversation with every owner and let them choose," he said. "We're covering the patient's ass."

Overall, all sources contacted by VIN News appear to agree more than disagree. Mackin, for instance, would tell the owner of a Labrador retriever that had eaten only one grape that the "very, very safest thing they could do" would be to give the dog fluids but "it's highly likely your dog will be fine." The difference in opinion surfaced in the nuance of the different conversations practitioners have with clients, with Wedderburn, for instance, suggesting that it's OK for veterinarians to recommend zero treatment in low-risk situations.

Sources concurred that treatment recommendations may depend not only on the size of the dog and number of grapes it consumed but the owner's situation.

"Let's say a lady comes in with a Chihuahua, and the Chihuahua is her complete life. Then I'd be more likely to say, 'Look, we'll just be a bit more cautious here,' " Wedderburn said. "But say someone else comes in with a big greyhound, they keep lots of greyhounds and they're a bit more, what you might call, rough and ready with their pets. It's a different type of response."

As for Grossman's pizza-joint-owning client in North Carolina, he has another Rottweiler now that's grown to a healthy 5 or 6 years old (with no grapes in his diet). Grossman said the client, who grew up in Italy, recalled being told as a child to keep dogs away from grapevines, thinking it was because people didn't want the grapevines ruined. Now, he wonders if they were onto something.