Photo by Brandy Galos

Ergo, now 4, has had a close relationship with Mike Galos, a computer programmer in Bellevue, Washington, since the day he and his wife adopted the dog three years ago. The Galoses’ financial wherewithal was questioned in a complaint to the veterinary board after the couple had Ergo spayed at the nonprofit Seattle Humane Society clinic, which is limited by law to serving low-income pet owners.

When Brandy Galos scheduled her newly adopted German shepherd, Ergo, for a spay at the Seattle Humane Society, she didn’t know that the nonprofit organization was limited by state law to providing veterinary services only to low-income households.

On the day of the appointment, her husband, Mike, checked in Ergo at the clinic while Galos waited in the car. As the minutes passed, Galos grew nervous, wondering what was taking so long. A half hour later, Mike finally appeared, explaining that he had to fill out a slew of paperwork that included questions about their financial status to determine whether they were eligible.

As it turns out, they were. “Unfortunately, my husband had been out of work for six months, so we qualified,” Galos said, adding, “I’d say as a rule, that’s not true for us. We’re pretty blessed.”

As residents of Bellevue, Washington, the Galoses live in one of the wealthiest cities in the state, a Seattle suburb where median household income exceeds $90,000. Considering that the median income in America is about $53,000, one might doubt that the couple is low-income. In fact, someone did.

Shortly after Ergo’s surgery, a private-practice veterinarian in Bellevue filed a complaint with the state Veterinary Board of Governors. The veterinarian suspected that the Seattle Humane Society had violated a statute that allows veterinary clinics run by 501(c)(3) corporations to provide limited veterinary services to the public, and only to low-income households.

The complainant, whose identity is confidential under state whistleblower protections, pointed to Ergo and another dog as belonging to owners who appeared to be well-off, yet were able to obtain spays at the Humane Society at a steep discount.

Washington is unique among states for legislating limits on nonprofit veterinary clinics. Enacted in 2002, the law lets nonprofit humane societies and government agencies charged with animal care and control provide a few specific services — namely, microchipping, spay/neuter surgeries and vaccinations — to pet owners with limited means.

Defining the purpose of the law, lawmakers stated: “The legislature recognizes that low-income households may not receive needed veterinary services for household pets. It is the intent of the legislature to allow qualified animal control agencies and humane societies to provide limited veterinary services to low-income members of our communities. It is not the intent of the legislature to allow these agencies to provide veterinary services to the public at large.”

Private-practice veterinarians who see some nonprofit clinics as unfair competition often point to the Washington law as a model. But an investigation by the VIN News Service found that the law does a spotty job ensuring that nonprofits serve only pet owners in financial straits.

A chief reason is this: The law says nothing about how the organizations are to verify that pet owners meet the income requirements — or even whether they must.

As Dr. Christine Wilford, a Seattle-area veterinarian who works in both private-practice and nonprofit realms, exclaimed to a reporter: “Your interpretation is that Washington has means testing? Because we don’t! I can walk in with my Beemer (BMW) and say I’m poor.”

All the same, Wilford believes that using the honor system is appropriate — an opinion shared by many in the nonprofit world, if not in private practice. Wilford said means testing “just slows everything down. And it can be very embarrassing. It’s hard enough to be poor.”

Some clinics seem to be scofflaws

On the whole, nonprofit clinics do acknowledge the law. Of 18 animal-welfare organizations that are registered with the state Veterinary Board of Governors, most that offer spay-neuter surgeries make at least passing mention on their websites that pet owners need a certain income to qualify. But two appear to disregard the requirement:

Nonprofits pushed for latitude; WSVMA pushed back

• Northwest Spay & Neuter Center in Tacoma states: “The center is open to anyone who wants to help decrease animal overpopulation in Washington State (or beyond).”

• Purrfect Pals in Arlington states that it “operates a free public spay and neuter clinic for cats and kittens weekly.” The one qualification specified is that kittens must weigh two pounds or more. A recording on the scheduling line says nothing about income limits.

Northwest Spay & Neuter Center Executive Director Melanie Manista-Rushforth confirmed in an interview that the center turns no one away. She said the “open to everyone” statement is meant “to help people understand that if they already have a relationship with their veterinarian, and our prices make sense for their family, we’re not going to exclude anyone from receiving services.”

The center’s prices for spay or neuter surgeries for dogs range from $75 to $130, depending on the weight of the animal; and $10 to $55 for cats, depending on sex and whether the cat is owned or feral.

Manista-Rushforth said all clients are asked whether they are low-income, and about 80 to 85 percent say they are. “We’re not turning people away, but the majority of our clients are low-income folks that are interested in having their pets spayed or neutered,” she said. “I don’t see that we’re doing anything wrong.”

Asked how that practice complies with the law limiting nonprofit clinics to serving low-income households, Manista-Rushforth said she would consult her board’s lawyer for his interpretation.

In a follow-up email, Manista-Rushforth said, “Upon double-checking with our legal counsel, we as an organization should just state that we serve the low-income population of Western Washington instead of stating that we serve everyone.”

She added: “We are planning as an organization to discuss the wording. I imagine we will change it to accurately reflect who we serve (the low-income population). I think we spend a lot of time and thought (especially in the Northwest where everyone is very politically correct) trying not to exclude anyone from anything, and in the process, we represent ourselves incorrectly.”

At Purrfect Pals, Executive Director Connie Gabelein acknowledged by email a VIN News Service request for an interview but did not respond to multiple subsequent telephone and email messages.

One organization, the Seattle Animal Shelter, states openly on its website that “no location or income verification (is) required” to access its low-cost or free spay and neuter surgeries for dogs, cats and rabbits. That’s because the shelter is exempt from the law, said Dr. Mary Ellen Zoulas, the clinic medical director.

“We were created by a mandate of the citizens of Seattle, and we existed prior to the law, so we were grandfathered in,” she explained, pointing to a provision in the law that reads: “Any local ordinance addressing the needs under this section that was approved by the voters and is in effect on July 1, 2003, remains in effect.”

Zoulas said she is sympathetic to the concerns of private practitioners, and therefore is careful to limit the clinic’s offerings. “Treating fleas and ear mites, as much as it would be easy for us, and to sell products and do a lot of add-on services, that would be competing with the private veterinary community, and I feel obliged not to do that,” she said.

Complaint spurs reform at one clinic

Enforcement of the restriction on nonprofits falls to the state Department of Health (DOH), under which the Veterinary Board of Governors operates. The department has no assessment of how closely organizations and agencies overall hew to the law; it investigates specific situations only if it receives a formal complaint.

“Financially, we’re not able to go out and inspect (facilities),” said Judy Haenke, a DOH program manager. “It’s complaint-driven.”

Photo by Alex Garland

The Seattle Humane Society drew two complaints in 2012 related to suspected violations of the law governing nonprofit veterinary clinics. The first led the organization to better publicize income-eligibility rules it must apply. The second complaint was not validated.

Information provided to the VIN News Service in response to a public-records request shows that the board has received two complaints directly related to the law since its enactment 13 years ago. Both were filed in 2012 against the Seattle Humane Society.

The first, lodged by the Washington State Veterinary Medical Association (WSVMA), contended that the humane society failed to state in promotions for its spay/neuter service that the service was available only to income-eligible pet owners.

Candace Joy, executive vice president of the association, said she called the veterinary board office after she was “inundated with calls” from members complaining that the humane society was advertising “spay day for anybody to come in and spay/neuter their pets.”

Responding to a consequent inquiry by state regulators, Seattle Humane Society CEO David Loewe explained in a letter that the organization’s marketing team since 2006, “used the term ‘low-fee spay/neuter’ as a euphemism for services marketed to low-income pet owners. This phrase was implemented to ensure that the term ‘low-income’ did not stigmatize or embarrass people due to their financial status or decision to use our services when they could not afford them at a private veterinary practice.”

He went on to say that “all customers sign a surgical consent form verifying that the pet owner’s income is 80 percent or below the median family income in King County. This has been a standard feature of the surgical consent form.”

Maintaining that the humane society had followed the law, Loewe said the organization, after speaking with the health department investigator, nevertheless made a variety of changes “in order to avoid any appearance of impropriety.” The changes included providing information about the income requirement on its website, in advertising, in electronic communications with customers and through staff who answer telephones.

The humane society website today states in bold type that “income qualifications apply” and displays a chart showing income thresholds based on household size in several counties.

In an interview, Loewe said pet owners aren’t asked for proof of income, in part because it may be genuinely difficult for them to produce. For example, he said, someone might say, “I don’t have a job, therefore, I don’t have a pay stub.”

“You really come down to the person’s honesty,” he said. “So I as a CEO and other (staff) around the table, no one wants to think we’re here to perpetuate fraud. That’s why we rely on someone’s signature and good faith that they do qualify for these services.”

Loewe admitted to a “light-bulb moment” during a conversation with the state investigator about humane-society procedures. The investigator pointed out that if someone made an appointment online without knowing about the income qualification, took time off work, prepared the pet for surgery and brought it in, only then to learn about eligibility criteria, “It would be easy to say, ‘to heck with it’ and sign the form” whether the statement was true or not, Loewe said.

With that in mind, he said, the organization added more references about income eligibility to the process.

Very few people have been turned away for not qualifying, according to Katie Olsen, chief operations officer for the humane society. “I’d say we have one a month,” she said. “In most cases, they don’t really make it through our front door. It’s about everywhere you can look on our website.”

In talking to would-be clients whose income disqualifies them from services, Loewe said he’s found often that “it’s not about, ‘I’m coming in to get something on the cheap,’ it’s ‘Oh, we love you guys. … We thought we could come in here and support you by having the service performed. I didn’t realize there was a restriction on that.’ ”

Joy, executive vice president of the WSVMA, said that in retrospect, she would have liked to have resolved the issue with the humane society in a less confrontational manner. At the same time, she said, the formal complaint was effective. “It was the catalyst for them to review their processes, and now they’re not doing that anymore,” she said.

Second complaint followed

Two months after the health department closed the first case, a another complaint against the Seattle Humane Society arrived citing suspected violations of the same law.

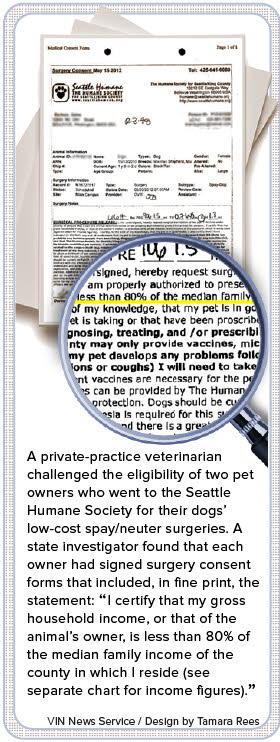

The complaint was filed by an anonymous veterinarian who speculated that owners of two dogs spayed at the humane society clinic had the means to pay market rates. That judgment was based on the fact the owners of one dog drove a Land Rover, a luxury SUV; and owners of the other dog worked at Microsoft.

The complaint was filed by an anonymous veterinarian who speculated that owners of two dogs spayed at the humane society clinic had the means to pay market rates. That judgment was based on the fact the owners of one dog drove a Land Rover, a luxury SUV; and owners of the other dog worked at Microsoft.

In a letter to a board, the complainant acknowledged not knowing the incomes of the dogs’ owners. “I am not in a position to know clients’ incomes to know whether a complaint is justified or not,” the veterinarian wrote. “We are also not in a position to determine means testing, or the integrity of means testing if it is done. Practitioners depend upon the Board (to) meet their obligation in RCW 1892.260(4)(c) ‘Ensure that agencies and societies are in compliance with this section.’ ”

In an interview with the VIN News Service, the veterinarian described having earlier written to the veterinary board to ask how it enforced the law. The board replied that it required a complaint to investigate.

The veterinarian said in the interview: “I’m not against what the humane society does, and is. … We appreciate what they do. We like rescuing pets. We want to support and foster that. We want them to be taken care of, but we’d like them not to have our clients (comparison) shop us against them. … I can’t compete with 1,300 volunteers, donated money, that kind of thing.”

Galos, one of the dog owners named in the complaint, said in an interview that the fancy car that raised questions about her low-income status was 12 years old at the time.

The VIN News Service was unable to reach the other dog owners named in the complaint.

Rhonda Parks Manville, vice president of marketing for the humane society, said in an interview that she finds “this whole car issue” superficial and offensive. “We have personally seen so many people come in here with a nice car, and they have just lost their home because they lost their job,” she said.

The Seattle Humane Society provided copies to the state investigator of the surgical release statements signed by the dog owners that they understood the service was available only for “income-restricted pet owners.”

Following a yearlong investigation, the board closed the case, stating that “a violation has not been determined.”

Competition needed or unfair?

Speaking generally about the case and law, Galos said she would like nonprofit clinics to be allowed to provide services to anyone. “What I thought when I was signing up for (the spay surgery) was that it was just another thing they did, and they made money off of them,” she said. “I thought, what a great thing for them to do, to make it cheaper for everybody, and (it’s) a way to raise funds. I thought it was a wonderful, win-win program.”

Galos said she and her husband had recently rescued their German shepherd, Ergo, from a neglectful home. Before scheduling Ergo’s spay at the humane society, Galos said she obtained an estimate from a private-practice veterinarian for the operation. The quote, she said, was $800.

“Even if my husband wasn’t laid off, 800 bucks to spay a dog is quite a lot,” Galos said. “… You start thinking, ‘Do I rescue this dog or let it die because I can’t afford a thousand dollars?’ So maybe they need a little competition here.”

The Seattle Humane Society price chart shows that it charges no more than $99 for spays or neuters.

The veterinarian who filed the complaint said many pet owners don’t realize that taking their business elsewhere, whether for spay/neuter surgeries or prescription medications, drives up the cost of care they do obtain from private practices.

“When you are used to doing a certain number of procedures, you determine fees appropriate for your costs plus percent profit,” the veterinarian said by email. “When you do fewer procedures, you increase fees as you need to maintain revenues. … Loss of procedures to nonprofits has resulted in the increased cost of doing these procedures at your local veterinary clinic. As a result, we are unfairly portrayed as villains for our fees.

“This has been an insidious aspect of this relationship (with nonprofits) over the years,” the veterinarian continued. “They are supported by donations in the millions, and have thousands of volunteers and do these procedures for fees that we simply cannot. …

“Point is, the lack of means testing and willingness of these agencies to accept all (pet owners) has a cost to the general public that is unrecognized and placed on the veterinary profession’s shoulders.”

Loewe, the Seattle Humane Society CEO, noted that private-practice veterinarians regularly refer animals to the humane society clinic for medical care when their owners can’t afford private-practice prices. Because the law restricts the types of services the nonprofit clinic can provide to the public, there’s only one way it can help.

“We have to say, ‘Yes, we will take care of them but you have to surrender the animal, and you can’t have it back,’ ” Loewe said. That’s because the shelter may provide a full range of veterinary care only to the animals in its charge. “It happens about once a month,” Loewe said. “It’s a tragic event for staff and family.”

Even so, Loewe said if the state didn't restrict nonprofit veterinary care, the humane society still would not look to provide a full suite of services to everyone regularly.

“Being in competition with the vet community seems to be about the worst model ever,” Loewe said.

“This is probably a geographic issue,” he added. “At least around here, we’ve got vets and private practices, corporate practices — they’re everywhere. They’re on every street corner. Why would we want to take our donor funds to go in direct competition with something that already exists? Our role is to serve the gap.”

Donors, not law, drive means testing

At Pasado Safe Haven, a nonprofit animal rescue group in Sultan, Washington, pet owners are asked for their household size and proof that they’re on public assistance. The request for documentation is driven not by the state law, but by the requirements of large donors, said Jenny Fraley, director of homeless-prevention initiatives.

The documentation requirements vary depending on where the pet owner lives. “We’ve got three programs on different funding, and some of the documentation is more relaxed,” Fraley explained.

The most rigorous requires not only that staff see the paperwork, but keep a record of the proof shown. The more relaxed programs that don’t require record keeping happen to pertain to the larger two of the three counties Pasado serves, accounting for thousands of spay and neuter surgeries each year.

“If we had to actually document it all, I wouldn’t be able to handle it all,” Fraley said.

Although the state doesn’t dictate income verification, the law has a decided effect on Pasado’s services.

“The law drives the fact that we can only help those that are income-qualified,” Fraley said. “So to be honest with you, if the law wasn’t there, we’d be more than happy to help anyone spay and neuter their animals. Because sometimes, you know, that’s all it takes, even for people who have the means to do it. They don’t want to spend the money on that. Unfortunately, it’s just a fact of life.”

Wilford, a veterinarian who runs a house-call practice in the Seattle area and founded a free spay-neuter operation for feral cats, agrees.

“My personal point of view and experience is that people might have a lot of money (but) the animals don’t necessarily get it,” she said.

Wilford told about a woman she knows whose husband (now ex) had a net worth exceeding $220 million. “She had a cat that (landed) in her lap. It needed to be neutered,” Wilford said. “Her vet quoted $80. Her husband said ‘no.’ ”

The experience stands in sharp contrast with one involving one of Wilford's private-practice clients: “Old lady, fixed income. She went back to work at McDonald’s for minimum wage so she could afford to pay our practice to perform spay/neuters for cats she was trapping in her neighborhood.”

The way Wilford sees it, the first woman’s cat was low-income. “This old lady who worked at McDonald’s, her cats were rich,” she said. “It’s not about if the human has resources. It’s about whether the humans with money will spend the resources.”