The veterinary economy is growing steadily again but attracting more patient visits appears to remain a challenge.

The veterinary economy is growing steadily again but attracting more patient visits appears to remain a challenge.

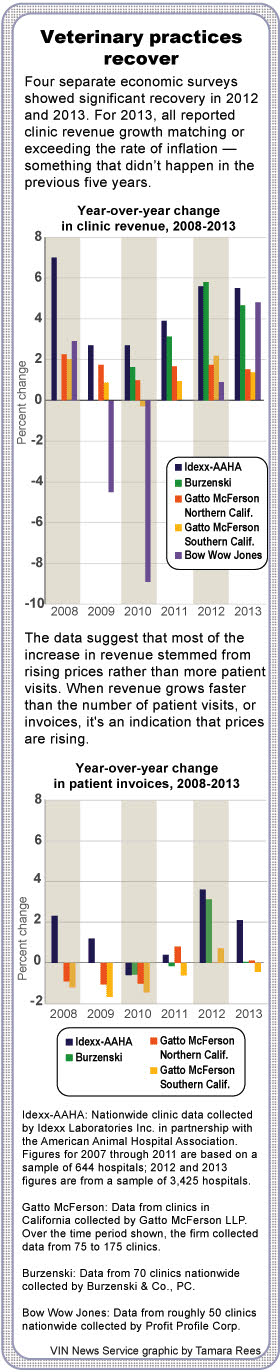

Four separate surveys agree that average revenue at U.S. veterinary clinics grew in 2013, with reported gains ranging from 1.4 percent to 5.5 percent.

While the figures are a big improvement over the economic downturn’s worst years, 2009 and 2010, they are a slight slowdown compared with 2012, according to three of the four surveys. In addition, most of the revenue growth in 2013 stemmed from price increases rather than increased patient visits, continuing a trend that worries some leaders in the profession.

“Growth based on price increases isn't a sustainable model,” said Dr. Mike Cavanaugh, CEO of the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA).

Practice-management consultants and veterinarians cited several factors influencing clinic revenue.

General economic indicators, such as the national unemployment rate, continue to improve, if slowly. Competition from mobile clinics and other low-cost service providers is eating into revenues from some basic services like vaccinations, but traditional veterinary practices continue to have a firm hold on other — and often more profitable — services, such as diagnostics. Data on sales of parasite prevention products suggest that at the same time that online and big-box retailers are seeing revenue gains from sales of flea, tick and heartworm prevention products, so, too, are many veterinary clinics.

Dr. Amoreena Sijan, who opened a solo practice in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in late 2009 after losing an associate job as the recession began, said business at her clinic has improved steadily over the past two years. The same appears to be true of other clinics in her area, she said, though a number of owners are putting in more hours and have stayed with the reduced staffing levels that got them through the slowdown.

“I think we're seeing the business owners having to work a lot harder than they did before the recession,” Sijan said.

The four economic surveys are based on data from companion-animal clinics provided by clients of the following firms: Idexx Laboratories (3,425 hospitals; survey conducted in partnership with AAHA); Gatto McFerson LLP (175 practices, in California only); Burzenski & Co. (70 practices); and the Bow Wow Jones index generated by Profit Profile Corp. (roughly 50 practices). For comparison, there are about 26,000 small animal veterinary practices in the United States, according to AAHA and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). The surveys do not include data from clinics that are part of large chains, including those run by VCA Antech Inc. and Banfield Pet Hospital.

Results from the Idexx survey, the only one to give information on the variance of revenue figures reported by clinics, indicate a wide range of economic performance within the profession. The survey found that 23 percent of clinics had revenue increases of greater than 10 percent in 2013; half grew 0 to 10 percent; and 27 percent saw revenues decline.

“I think that spread is greater now than it used to be,” said Dr. Karen Felsted, who runs PantheraT Veterinary Management Consulting in Dallas and is the former director of the National Commission on Veterinary Economic Issues (NCVEI). “Some are really working hard to react to the new veterinary environment, some haven't made as many changes.”

A key challenge for the profession, most consultants agreed, is augmenting good veterinary medicine with strategies to increase patient visits.

“This is where most practices are struggling,” said Gary Glassman, a certified public accountant and partner with the practice management consultancy Burzenski & Co. in East Haven, Connecticut.

Promoting preventive care is one approach AAHA and AVMA see as having substantial potential to increase patient traffic. The groups are leading an effort called Partners for Healthy Pets to help practices boost patient wellness visits. The program provides free print and social media marketing guidance, advice for communicating with clients about preventive health care, and other suggestions.

AVMA and AAHA view raising the overall demand for veterinary services as a way to deal with two of the profession’s biggest challenges: the rising number of new veterinary college graduates and growing student debt.

A 2013 AVMA study found that demand for veterinary services in 2012 in the United States was enough to fully employ just 78,950 of the country’s 90,200 working veterinarians. In the past decade, the number of students graduating from veterinary medical colleges in the United States grew by 22 percent, from 2,209 to 2,686, according to data from the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, and more colleges are opening.

Historically, prices for veterinary services, the other big variable in the clinic-revenue equation, grew more slowly than inflation. From 1972 to 1996, veterinary price increases lagged inflation by about 25 percent, a trend that prompted calls to raise fees.

“The idea that veterinarians were undercharging for their services got hammered into people’s heads,” said Cavanaugh.

The price trend reversed in the mid-1990s, and prices for veterinary services increased 91 percent from 2000 to 2013, compared with inflation of 35 percent over the same period, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

By about 2008, the veterinary sector had made up the lost ground. In 2013, veterinary prices increased an average of 3.4 percent over the previous year, compared with overall inflation of 1.5 percent.

“I think prices needed to increase; that was appropriate,” Cavanaugh said. But if prices continue to rise much faster than inflation, Cavanaugh said he is concerned that may limit the number of people who seek regular care for their pets, an important factor for the long-term financial health of the profession.

A 2011 study commissioned by Bayer Animal Health identified prices as one of the three top reasons for declining visits. The same study reported a steady decline in the average number of patient visits per veterinarian starting in 2003.

It isn’t yet clear whether price increases are driving enough clients away to affect profits. A 2010 study by the NCVEI estimated average profits at private practices at 10 percent. The periodic surveys of clinic revenue don’t measure profits, so information isn't available on changes in profitability. Figures on changes in the costs of operating a veterinary practice also are scarce.

To better understand the impact of pricing on clinic business, AVMA this year launched a study of how consumer demand for veterinary services is affected by changes in price. Initial results are scheduled for release in October.

Financial filings from VCA Antech Inc., which operates 609 veterinary clinics in North America, provide what may be the only publicly available data set on trends in patient visits, prices and profits over time for a large number of clinics.

In each year from 2001 through 2013, VCA has reported a decline in visits to its existing clinics (that is, not counting newly acquired clinics) and an increase in the revenue per invoice, a measure of prices.

Despite the declining visits, VCA maintained operating margins (profits before income taxes and interest expenses) on its animal hospital business of more than 16 percent through 2009. Since then, profitability has slipped; the company reported operating margins of 11.7 percent in 2012 and 12.1 percent in 2013.

For independent practice owners, price-setting can be complex. Dr. David Harriton, who owns The Animal Hospital of Barrington in New Hampshire, said his prices have been going in two directions recently.

“Some of my prices I haven't increased in years,” he said. In fact, Harriton has cut what he charges for vaccines and some medications in order to remain competitive with retailers and a new mobile clinic in his area. But he has continued to raise the price of office visits and laboratory and surgical fees.

“I’m walking a tightrope,” Harriton said. “Obviously, the profession has changed dramatically. The cream on top is getting smaller and smaller and more split up.”