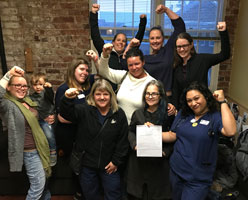

Workers at VCA-San Francisco

Photo courtesy of ILWU

Workers at VCA San Francisco Veterinary Specialists celebrate their vote in April to unionize.

Support staff at two West Coast veterinary specialty hospitals have voted to join labor unions, an unusual development for a profession in which collective bargaining has been, up to now, almost nonexistent. The votes came seven months after fledgling efforts to organize workers first made headlines.

At VCA San Francisco Veterinary Specialists, veterinary technicians, assistants, maintenance personnel and customer service representatives voted 56–20 in April to affiliate with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU).

In late May, workers representing the same job functions at BluePearl in North Seattle voted 46-4 to join the new National Veterinary Professionals Union (NVPU), with legal and organizing support from ILWU.

With more than 850 facilities in the U.S. and Canada, VCA is the largest standalone hospital chain in North America. BluePearl is a group of emergency and specialist-referral hospitals with 66 locations in the country. Each company confirmed these are the first successful votes to unionize. Both are owned by Mars Inc., the largest owner of veterinary practices in the world.

Now, the new unions will try to negotiate a contract. NVPU president Liz Hughston said support staff at other veterinary hospitals are organizing, as well, and more union votes are expected this year.

Employees who support the unions want improved workplace safety, training, staffing and retention; and better compensation and benefits.

“These aren’t new issues. They’ve been around,” said Laura Territo, a veterinary technician at VCA SFVS who serves on the communication action committee for her new union. Salaries don’t come close to covering the high cost of living in the San Francisco area, she said, and “we have a benefits package that’s not [worthy of] a company that’s worth billions.” (In 2017, Forbes magazine ranked Mars, which is family-owned and -operated, as the sixth-largest private company in the U.S., with $35 billion in sales.)

While salary and working conditions long have been a source of dissatisfaction for veterinary technicians, the fortunes of the parent company appear to have tipped the scales toward action. Territo and other veterinary technicians involved in the labor movement cited the consolidation of independent practices by large corporations such as Mars as a key driver to unionizing.

In addition to BluePearl and VCA, Mars owns Banfield Pet Hospital, the largest clinic chain in the country, and Pet Partners, a practice chain with locations predominantly in the eastern half of the country.

“When you are talking about these corporate practices, there are so many levels … you feel completely powerless,” said Hughston, who also is a veterinary technician. “You can complain and complain and complain, and you’re a voice howling in the wilderness, because nothing happens.”

Mars declined to comment for the story. VCA opted not to answer VIN News Service questions about the union at its San Francisco hospital, and provided this statement:

Tana_Greatorex

VIN News Service photo by Lisa Wogan

Veterinary technician Tana Greatorex helped lead the effort to form a union for BluePearl support staff.

“At VCA, we recognize that our team members’ knowledge, dedication and valuable skills are essential for us to be able to deliver on our promise of compassionate veterinary care and excellent service to our clients. As a company, we work very hard to develop a culture where our team members are appreciated and supported throughout their careers. We are disappointed that we are not able to continue to work directly with our team members to address issues that we were already in the process of resolving.”

BluePearl also declined to be interviewed, and gave this statement: “We care deeply about all of our associates and know they are essential to our ability to deliver compassionate, advanced care for pets. We were saddened to learn that some team members felt the need to form a labor union to address issues that we were already in the process of resolving. As always, we are working to better understand the concerns of all of our associates and remain committed to the industry, our associates and to quality care for our patients.”

Asked whether the drive to organize might spread to smaller, independent practices, Hughston expressed doubts. “That’s not really a target for our movement because those people have a voice in their practice because it’s smaller,” she said. “Everyone is there working on the floor.”

She said she believes that when veterinarian-owners see faulty equipment or support staff working long hours, they are more likely to be responsive about making improvements. In some corporate practices, it seems that first-line managers put workers off and let requests fall by the wayside, Hughston said, leading to worker frustration.

That frustration mounts when staff see the parent company spend billions to expand around the world. Weeks after the BluePearl union vote, Mars announced the purchase of two more practice groups, bringing nearly 300 sites in the U.K. and continental Europe into the company fold. These acquisitions are now among organizers’ talking points.

“Things are in dire straits for our technicians,” said Dr. David Gill, a BluePearl veterinarian who actively supports NVPU. “We’re losing ground. We’re losing staff. It impacts the quality of care.”

Gill calls out Mars by name and criticizes the company for not doing enough to keep up with technicians’ cost of living, even as it seems to have ample cash. In addition to Mars’ spending on acquisitions, Gill cites a story by a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, that explores how the Mars family repeatedly has avoided paying billions in estate taxes. “None of that seems to be trickling down,” Gill said.

Pay issues drive movement

There have been a smattering of unions at private clinics, universities, research institutions and one nonprofit hospital, but a national initiative with two locations and more votes in the works is new territory. NVPU originated in Seattle, with current and former BluePearl North Seattle support staff coming together over common complaints. Former veterinary technician Morgan Van Fleet, who now is in nursing school, helped drive early conversations among local staff and online. Workers in San Francisco joined in the larger discussions and connected with the ILWU.

Last year, NVPU discussed the possibility of including veterinarians along with support staff in the union but that proved difficult, according to Hughston. Because they direct other people’s tasks, veterinarians can be considered management, which could have created difficulties in negotiating a contract down the road. “Unfortunately we can’t include them in the movement now, but I don’t know what the future may bring for them in terms of organizing,” she said.

According to Tana Greatorex, a veterinary technician at BluePearl and NVPU vice president, conversations among support staff centered around a lack of annual reviews, high turnover, poor benefits, inadequate salaries and the lack of cost of living increases. “While I am assisting on thoracotomies … my sister is being paid more to check groceries,” she said.

A 2016 survey by the National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America found that full-time technicians reported an average salary between $15 and $20 per hour. “Well-paid veterinary technicians are only slightly above the poverty line once income taxes are considered,” the survey authors said.

“You can’t live, particularly in the Pacific Northwest or in California, on what they pay technicians,” Hughston said. “It’s not a sustainable profession. The statistics bear that out. We see that people leave the profession in 5 to 7 years.”

The union process

Form or join a union

Establish employee interest

Notify management

Vote to certify the union

Negotiate a contract

Can a union be removed?

Greatorex, who said she’s been able to stay in the field because of her husband’s salary, argued that curbing turnover should be a hospital priority since having to replace workers is expensive and also affects patient care.

More than a year ago, BluePearl management got wind of union talk at the North Seattle location and called staff meetings, Greatorex said. One of the complaints from employees, who had shared salary information among themselves, were “large discrepancies in pay.”

This happened around the time that Mars announced plans to purchase VCA in a deal valued at around $9.1 billion. “You just bought our competition and you can’t pay us a fair wage?” Greatorex remembered thinking.

She said the company made some improvements, but the “overall picture” did not change. Gill said a series of recent salary increases were well below the rising cost of living.

Owners voice concerns

In the weeks after employees officially declared their intent to form a union and before the secret ballot, there were a few weeks of open campaigning at both clinics, which is allowed by law.

“It was pretty trying for all of us,” Territo said. “Managers were pulling us aside, saying, ‘Do you know anything about the union?’ I mean, they weren’t discouraging us, but it was kind of like they were using anti-union tactics.” Employees were given an FAQ prepared by the American Veterinary Medical Association, that notes, among other things, that while the union has the right to request an employer make changes, “the union cannot require anything of the employer.” Territo said upper management emphasized that point during meetings.

In a statement provided to VIN News, the AVMA said it takes a “neutral approach” on unionization. Reiterating the preface to its online FAQ, the statement went on: “The AVMA respects the right of its members who are employees to self-organize, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, and to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing. We also respect their right to refrain from any such activity.”

In its own statement and FAQ about unions, NAVTA follows almost word for word the AVMA’s.

In the pre-vote period, the hospitals held required “town hall” meetings for employees. Territo said VCA Chief Operating Officer Arthur Antin attended. “That kind of told us that, ‘Hey, we did something here,’ ” she said.

According to Territo and Greatorex, among the arguments against the union raised by corporate representatives were the role of the ILWU, which has no experience in veterinary medicine; the prospect that union dues would wipe out any potential gains — or worse — for staff; and concerns that strikes potentially would impact the hospital’s ability to care for the animals.

“They said, ‘We don’t want the longshoremen in here,’ ” Territo said. “We really tried to convey to them, the longshoremen aren’t coming in here. They are helping us. This is our union.” Hughston describes the ILWU as pursuing a bottom-up structure to support the employees who want to organize. “When Mars and VCA talk about ‘the union is doing this and doing that,’ they are talking about their employees,” Hughston said.

The ILWU, which began as the Pacific Coast District of the International Longshoreman’s Association in 1934, has more than 50,000 members.

The ILWU provides expertise and legal help. The relationship between ILWU and NVPU is not yet fully defined, Hughston said. It may be that NVPU becomes the equivalent of the “local” for veterinary practices within ILWU. Or they may end up with another partnership relationship.

For now, union members at the clinics are not assessed dues. Those will be determined by workers after the contract is ratified. Territo said she expects dues to be minimal, along the lines of 2½ times an employee’s hourly rate per month, or 1.4 percent of an annual salary.

The ILWU declined to be interviewed for this story. Hughston told VIN News, “They don’t want to distract from the story itself.”

In a column published this month in Today’s Veterinary Business, a publication of the North American Veterinary Community, Mark Cushing voices concerns about unionization and the ILWU’s involvement. Cushing is a lawyer and lobbyist whose client list includes Mars-owned Banfield and NAVTA.

“The partnership with an international union inexperienced in animal care promises to draw a great deal of attention as the ILWU has a long and aggressive history in organizing, strikes and political activities,” he wrote. “A pressing question will be the effect on practices if the union decides to strike or protest when bargaining is unsuccessful. We might soon see pickets and protesters outside of U.S. small animal clinics.”

Cushing’s concerns echo what Territo and Greatorex report the companies said during meetings with employees, where the idea of the union forcing a strike was upsetting to staff members.

“When they said the part about us going on strike and the animals [suffering], that really hit a nerve," Territo said, calling a strike "a last, last resort" that would have to be approved by a vote of members. “My mom was a teacher for 32 years; she never went on strike.”

The arguments did not dissuade employees, who voted for the union by a wide margin. Cushing speculates in his column on the potentially negative fallout.

“It is hard to view the unionization effort as not impacting the financial conditions of veterinary hospitals,” he wrote. “If practices are forced to bargain with the ILWU-backed union, one could expect salaries and benefits to go up and working hours or conditions to be affected. Veterinary practices might absorb the costs or pass them along to the pet owner, and there might be pressure to reduce staffing.”

Some individual practice owners share that worry. Dr. Helen Sutthill, who owns a practice in rural Oregon, supports unions but expects they will change the profession for better and for worse. On the plus, “They can be a wonderful help in keeping the balance of power more equal," she said by email. "As far as large corporations go, I think that veterinarian unions, as well as veterinary support staff unions, would level the playing field as far as workers' rights and wages.”

She went on: “Having said that, I also think they will cause the price of veterinary medicine to rise, perhaps pricing it further out of the reach of the ‘average’ person. I also think it will put more solo practitioners out of business, especially in rural areas like the one I practice in.”

Sutthill said attracting and retaining quality support staff always has been difficult and she expects it to worsen because she can’t compete in terms of wages and benefits. “I am lucky to have a kind, caring, intelligent staff at the present time, and I think being a fair employer is part of what keeps them here,” she said.

Contract negotiations begin

During the coming year, representatives from the unions, aided by their lawyers, will negotiate with VCA and BluePearl management and their lawyers to try to secure a first contract. It is a delicate moment for everyone concerned.

“We want to work collaboratively with management,” NVPU’s Hughston said. “It doesn’t have to be adversarial. I think if we work together we come to better conclusions and solutions.”

Public statements from BluePearl and VCA also strike a conciliatory, if disappointed, tone — praising the value of staff and citing an already ongoing process to resolve issues.

In a Human Rights Policy posted on the company website, Mars says it respects employees’ right to join, form or not to join, a labor union. It continues: “Where Associates are represented by a legally recognized union, we are committed to establishing a constructive dialogue with their freely chosen representatives. Mars is committed to bargaining in good faith with such representatives.”

In ILWU's view, though, the coming negotiation might be less than amicable. An article on its website says VCA/Mars’ decision to “retain the notorious anti-union law firm of Littler-Mendelson” might be a sign that the company plans to drag out contract negotiations with the aim of frustrating workers and encouraging a vote to decertify the union in a year.

For their part, veterinary technicians who are active in organizing are adamant that the process will not get in the way of the work they do. “Dedication to the patient and to veterinary medicine is really what keeps my co-workers going," Territo said. "We care about the pets and the people who love them — bottom line.”

This story has been changed to remove a reference to an online resource that is no longer available.