Swinging veterinarian graphic 288

Digital art by Tamara Rees

Source: Adobe Stock/impressed-media.de

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

With six months to go before graduating veterinary school, Ricky John Walther heard classmates talking about receiving job offers so, although it seemed early, he posted his resume on a job board.

The response overwhelmed him. "I got at least seven emails in the first 12 hours," he said.

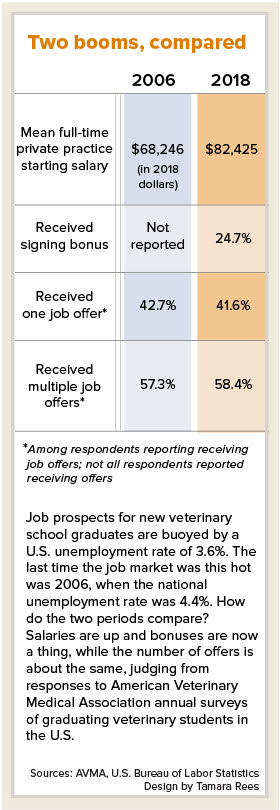

In his talks with prospective employers for jobs in his desired market around Davis, California, the proposed salary ranges of $100,000 to $120,000 have been close to or more than what Walther expected. Perks include signing bonuses, student-loan payoff assistance and shortened workweeks.

The fourth-year student from the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine ventures to tell recruiters he'd like a four-day workweek and would rather not work overnight or both weekend days. No one blinks. "It is cool to be in a job market that I can say things like that," Walther said.

Amid the longest economic expansion in U.S. history, the market is blazing hot for job seekers, and veterinarians are no exception. In fact, the profession is doing better than most, by the estimation of the U.S. Labor Department, which forecasts a "much faster than average" 18% growth in jobs for veterinarians from 2018 to 2028.

Ask any veterinary practice employer, whether a large corporate consolidator or a small independent clinic, what it's like these days trying to find associates, and all seem to agree: Competition for doctors is fierce.

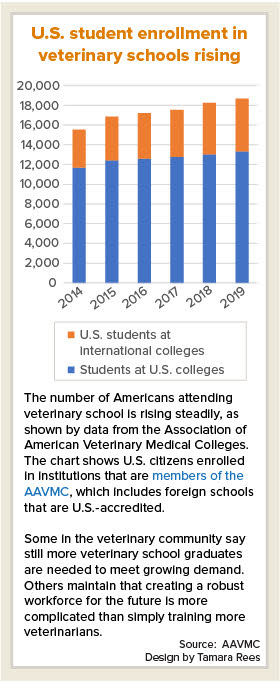

That's led some to conclude that the nation has a shortage of veterinarians, and that part of the solution is to expand existing veterinary schools and establish more. This fall, two new schools, in Arizona and New York, received the go-ahead to open. They plan to admit their first students in 2020. A third new school is under construction in Texas. Its advocates hope to open in 2021. And an existing school, Lincoln Memorial University in Tennessee, is seeking to double its enrollment, making it the largest veterinary program in the country.

Still more schools are being contemplated. The CEO of a small but growing veterinary practice group in Florida, Global Veterinary Partners, told the VIN News Service recently that competing for new graduates in his region is so difficult that the private-equity investors who own his company want to help fund a new veterinary school in Fort Lauderdale. And in New Jersey, the city of Vineland is funding a feasibility study on establishing a veterinary school in town, according to a local media report.

Within the veterinary community, however, there's no consensus that producing more veterinarians is the answer, or even whether a bona fide workforce shortage exists.

Within the veterinary community, however, there's no consensus that producing more veterinarians is the answer, or even whether a bona fide workforce shortage exists.

Count Matthew Salois, chief economist at the American Veterinary Medical Association, among those who doesn't define the situation as a shortage.

Salois understands that employers are feeling the crunch, but he points out that they're not the only players in the market. "Think about this," he offered: "Are there pet owners out there who are having trouble finding a veterinarian? Are they waiting weeks or months to get into a clinic for their pet to be seen? I think the answer to that, we all know, is 'no.' ...

"From the consumer/pet owner perspective, they don't see this [shortage] at all," Salois said. "If they did, it would have been front-page news in the Washington Post."

Moreover, graduating more veterinarians isn't a sure solution to employers' demand for more clinicians, he maintains. "I'm not saying we don't need more veterinarians and veterinary colleges, but I'm saying that the problem isn't going to necessarily be fixed by graduating more veterinarians," he said.

Why? Because schools do not control where their graduates work. And while there are more veterinarians in private practice than in the past, a critical part of the sector — specifically, those who identify as general-practice clinic owners or associates — is losing ground to other sectors of veterinary medicine, Salois said.

One reason is that career options outside of conventional clinical practice, such as relief work, industry positions, not-for-profit clinics and government, are expanding in number and availability.

"Quite simply, we have seen an increase in demand for veterinarians above and beyond just in the practice, as issues related to One Health [the concept that the health of people, animals and the environment are intertwined], for example, become more and more important to governments, companies and other organizations,” he said.

Consequently, "there's no reason to expect that if we opened two, four or five more schools, that would change anything," Salois said.

Trying to solve private general-practice labor needs by graduating more veterinarians is like filling a bathtub with an open drain, he said. "Instead of closing the drain, you turn up the faucet even more to try and keep the water levels steady. At some point, the drain wins."

Counting help-wanted ads, estimating jobseekers

Dr. James Lloyd, a veterinarian and economist, believes a labor shortage exists and argues that training more veterinarians is at least part of the answer. A former dean of the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, Lloyd retired from academia in May and started a consultancy, Animal Health Economics LLC. His first commission came from Animal Policy Group, an industry advocacy and public policy firm led by attorney and lobbyist Mark Cushing, whose services include school-accreditation counsel and political strategizing.

Cushing hired Lloyd to look at the employment market for veterinarians. "We wanted to establish data to quantify what anecdotally is understood by everyone in the industry, in virtually every state, that we are facing acute shortages of veterinarians — large practices, small practices and everything in between — and begin to put numbers to it so it wasn't merely anecdotal," Cushing said.

Lloyd produced a nine-page report, Characterizing the Current US Employment Market for Veterinarians — June 2019. He presented the findings for the first time in September at the Banfield Pet Healthcare Industry Summit in Portland, Oregon, and again in November, at the Rural Veterinary Education Summit at Lincoln Memorial University.

In his Portland talk, Lloyd said, "There's a bit of a frenzy — to me, I would characterize it as that — in the hiring market." He concluded that a shortage exists. Much of the subsequent discussion at the gathering, which included leaders in industry, associations and education, centered on that presumption.

The study consists of a review of online job postings in late June, primarily on indeed.com and the American Veterinary Medical Association career center website, plus a few others. Lloyd estimated the population of potential jobseekers by taking the number of 2019 fourth-year student enrollments (about 4,000, according to Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges data) and subtracting the proportion that typically has secured a job by graduation (60%, judging from annual AVMA surveys of seniors).

He reported that nearly twice the number of positions were available than jobseekers during the snapshot in time examined: 3,100 openings advertised versus about 1,600 new graduates looking for work.

He reported that nearly twice the number of positions were available than jobseekers during the snapshot in time examined: 3,100 openings advertised versus about 1,600 new graduates looking for work.

The picture of a profession short on help was filled out through conversations with more than two dozen individuals with experience as employers and who serve as "opinion leaders" across all sectors of the profession: companion animal, equine, and food animal private practice, academia, government and industry.

Asked how he chose whom to interview, Lloyd told the VIN News Service that they are people he knows in his network — which he described as extensive — along with referrals. "It was a convenience sample, for sure, and I'll own that," he said.

The interviews "almost uniformly indicated a tight employment market with a relative scarcity of candidates for the number of positions available, thereby validating the results of the purely quantitative analysis," the study states.

The job market could "easily provide solid employment opportunities" for as many as 2,000 more graduates, adding to the 4,000 or so Americans already entering the workforce each year from veterinary institutions, Lloyd's report concluded.

A separate study commissioned by the AAVMC and Animal Policy Group, the private consultancy, also authored by Lloyd, identifies a potential source of hundreds more veterinary students: rejected applicants. Reviewing the grade point averages and standardized test scores of 2018 veterinary school applicants, he found "a huge overlap" in performance of those who were accepted and those who weren't.

"[A] rich ... applicant pool clearly existed in 2018 beyond the group that was offered admission," the study states. The data "suggest that from 61% to 91% of the non-admitted candidates were as capable academically as the least capable students in the admitted pool. Numerically, this represents over 2,000 academically-qualified candidates" who were turned away.

Missing data

Another well-known veterinary economist, Michael Dicks, agrees that the market could use more veterinarians. By his analysis, which factors in expected retirements, growth in household incomes and growth in pet-owning households, the number of new companion animal practitioners produced between 2012 and 2018 was an average of 2,743 per year fewer than needed.

However, Dicks, who preceded Salois as AVMA's chief economist, serving in that role from 2013 to 2018, doesn't characterize the gap as a shortage. The term he uses is "capacity," as in, is the workforce being used to its full capacity? A clinic with a lot of downtime would have excess capacity. At the other end of the spectrum is negative underemployment, a mind-twisting term indicating that employees — in this case, veterinarians — are working more hours than they prefer.

Dicks believes the labor squeeze is a short-term phenomenon that reflects the state of the overall economy. "It's not a long-term event," he said.

That's not to say he thinks the profession should carry on as usual. Dicks says the profession is overdue for a serious overhaul, from the way veterinarians are educated to their business practices. He gave his view of the problems and some approaches for reform in an eight-part commentary published this year by VIN News.

To address labor volatility, simply mapping current supply and demand isn't particularly helpful, Dicks maintains. He advocates forecasting future needs through modeling. That approach requires lots of data. For example, the profession has no estimates for labor-force reductions due to illness, injury, family needs, career change or death, Dicks said. There are no measures for full-time-equivalent veterinarians entering or exiting the profession. No estimates of changes in efficiency that may happen when work previously done by veterinarians is delegated to veterinary technicians or other staff. No calculation of the paradoxical increase in productivity that can result when employees work fewer hours.

"All of these items are important, and setting a forecast is infinitely more important than the current supply/demand relationship," he said.

Lloyd acknowledged that a full structural analysis of the labor market for veterinarians would include much more information but said he didn't have the time or resources for that level of research; nor was Cushing, who paid for the work, interested in a study of that scope. "But I think there's a lot of information that we can glean from the work we've done," Lloyd added.

While the study wasn't expansive, Cushing said, "hopefully [it will] light a fire for others to look at other ways of studying it."

As for the tight labor market, Cushing disagrees that it's tied strictly to the current economic expansion. "There's a social and cultural shift that's well underway," he said. "I think the bigger factor out there is that millennials are now fully in the marketplace, and they have jobs. Not only do they own more pets than any other demographic group, but they're willing to pay for [their] health care."

How employers sell themselves

In the scramble for employees, employers are pitching themselves, rather than being pitched by applicants.

Dr. Everett Mobley

Facebook screenshot

In a video posted on Facebook, Dr. Everett Mobley uses humor and charm in attempt to find an associate for his practice in Kennett, Missouri.

Dr. Everett Mobley, owner of a clinic in the small town of Kennett, Missouri, took to Facebook in September with a humorous video advertising for an associate and possible successor. Business is booming, and the 66-year-old veterinarian is looking for a doctor with whom he can share the success and the knowledge he’s gained from 41 years in practice.

Mobley talks up the virtues of living far from a big city: no traffic, cheap public utilities, including high-speed fiber optic internet, and "terrorists will never find us."

"So here's the offer: It's practicing high-quality veterinary medicine, dealing with all kinds of people across the economic and social spectrum,” he says. "Small town life. Songs! Jokes! And an opportunity for practice ownership. I'm not getting any younger here. And the cash flow would fund your purchase, your student debt and a living wage. So call me!"

Three months later, Mobley reports that he's gotten some calls but the position is still open. He remains upbeat. "Communication is the universal solvent," he told VIN News. "You can't do anything without starting to talk."

According to Salois, the way to plug the drain of veterinarians from private general practice is to make it more attractive. Significantly boosting pay is one obvious way. "If a clinic or hospital were to, say, offer a starting salary two times the average, I doubt they would have any difficulty filling the position," he said. "They are having trouble filling the position at the rate they are willing to pay, which is constrained by how much revenue a veterinarian can generate."

Good salaries aren't the whole of it. "[A]ll the other perks and amenities are equally important," Salois said, "like flexible hours, enhanced health/life benefits, more mentoring and professional development, a focus on employee engagement and well-being, etc."

Employers have gotten the message and are responding in kind.

"[B]enefits need to continuously evolve to meet the changing needs of our workforce, given the 'medical, dental, vision, 401K' of the past is no longer enough," Tamara Robertson, vice president of talent acquisition at Banfield Pet Hospital, the largest general-practice chain in the U.S., with more than 1,000 locations, said by email.

Banfield benefits and enticements now include contributions to student-debt payments, flexible schedules, support for volunteerism and suicide-prevention training, she said.

Likewise, Pathway Vet Alliance, a fast-growing Texas-based consolidator that owns more than 200 practices and counting, is "committed to supporting families, flexibility, financial wellness and mental health," said Andrea Clayton, the company's chief people officer.

For example, she said, Pathway plans as of Jan. 1 to provide eight weeks of paid parental leave, whether for a birth, adoption or foster, to primary caregivers — moms and dads alike. It's also rolling out relocation support so that new hires who must move to accept a Pathway job can do so "cashless," she said, in recognition of the financial hardships many new graduates face.

At any given time, Pathway has 100 or so openings for doctors, and the company's goal is to fill vacancies for general practitioners in 120 days or fewer — a goal that Clayton said they've typically been able to meet or beat.

One hospital's experience

Finding emergency doctors and specialists is a different matter. That can take up to a year, she said: "You may be literally waiting for someone to finish residency."

She elaborated, "Given shortages in the specialty and emergency space, we can spend nearly a year nurturing and building a pipeline of candidates, and are nearly always in a competitive war for talent at offer stage."

While more generous and varied employment benefits are a sign of intense competition for employees, Clayton and Robertson agreed that such benefits are becoming the standard and aren't likely to be withdrawn in a slower economy.

"How do we say that we support families, saving for retirement, and promoting financial and emotional wellness ... only [to], when the times get tough, cut those programs when they are likely needed more than ever?" said Clayton. "People understand in tough times forgoing a pay raise, but cutting programs is both challenging and not an area I would focus on in a downturn."

Swinging from too many to too few

Anyone who's been in the profession for a decade or longer likely remembers the Great Recession of 2008 and the economic hangover that lingered years afterward. Many in veterinary private practice spoke ominously of a workforce oversupply.

According to a rough calculation by Dicks — using U.S. Census Bureau figures on household income and expenditures on pets, and data from his own research on veterinarian productivity — the number of veterinarians for each available job grew from fewer than one in 2008 to nearly three veterinarians chasing each job in 2013.

The situation reversed between 2012 and 2018 as median household incomes increased and the number of pet-owning households rose, Dicks said.

Jai Sweet, senior director of student development and academic services at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, has witnessed that swing through the microcosm of the school's annual career fair.

“Before the economic downturn, we would get 50 to 55 practices that would come and interview students," Sweet said. "Then it dipped [to] an all-time low of about 10 practices that came. Now we are back up in the 40s again.”

There is no ignoring or escaping the power of the economic tides, in Dicks' view. "This enormous whiplash in economic activity has created significant labor variability in not only the veterinary profession but in all professions," he said.

While no one expects another Great-Recession-sized downturn any time soon, history foretells that a recession will come. It's what markets do: They expand and contract. And the prospect of a contraction following a marathon expansion causes great anxiety, Salois, the AVMA chief economist, observed.

"This super cycle era of growth, being as long as it has, we've almost become addicted to economic growth," he said.

His advice: Don't fear its end. Using metaphors from nature and modern life, Salois said, "Even a tree knows when to stop growing. There comes a point, on an airplane, that we reach maximum altitude.

"You don't have to have a growing practice to be a successful practice," he mused. "I think we need to take a step back and talk about what it means to thrive. Instead of focusing on growth, you can look at efficiency, profitability, well-being."

For example, he said, how engaged are employees in a practice? Are employees' skills put to full use? "The majority of independent practices are inefficient," Salois maintained. "They're not leveraging their staff optimally, especially [their] veterinary technicians."

Practices that define and pursue success through measures other than or in addition to growth should do well at any point in the economic cycle, Salois said: "I'd rather be the owner of the most well-run practice than the one with the highest growth rate."

In any case, he said, responding to swings in demand for veterinary services requires long-term planning because it takes years for new veterinarians to be produced — one year for applications plus four years for schooling.

"Fundamentally, I think it comes down to every practice adopting a five-year mindset, and with that, being able to thoughtfully answer the question 'How many veterinarians will I need in five years based on demand for veterinary care?' " Salois said. "... Easier said than done, but taking an honest and critical assessment of your practice, its strategy over the next five years, and where you see the market and demand heading will help complete the puzzle."

At the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, Dr. Juan Samper has a front-row view of the annual rush for jobs and employees. A clinical professor and associate dean of academic and student affairs, Samper said opportunities for new graduates have been on the increase for five years, whether their practice interest is with small animals, large animals or a mix.

He cautions veterinarians to not get used to it. Having lived through the economic downturn as a 20-year practitioner of equine reproductive medicine in Vancouver, Canada, he warns that "things can change at any time."

"I tell students, 'You need to be able to reinvent yourself,' " he said. "Nothing is forever, not even this job market."