Lawsuit art

Six veterinarians working for Pet Emergency Clinic (PEC) in Spokane, Washington, were given an ultimatum in October 2017: Sign an agreement not to compete within a 25-mile radius of the clinic or be fired. It was a harsh requirement, given the restriction included most of metropolitan Spokane and would remain in effect for five years after the veterinarians left PEC.

Drs. Dru Choker and Matthew DeMarco, who had worked for 10 years at the emergency clinic without a formal contract, opted to part ways with their employer rather than accept those restrictions. They later learned that as PEC shareholders, they still were subject to the noncompete under the terms of a non-binding agreement PEC had signed with National Veterinary Associates Inc. Based in Agoura Hills, California, NVA has acquired more than 600 practices in the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand, according to information on the company website.

NVA had been in negotiations to buy PEC. As a condition of the deal, PEC shareholders — a group of about 50 veterinarians in the community that included Choker and DeMarco — would agree not to compete with the emergency clinic. Moreover, shareholders who worked in general practice would be obligated to refer patients needing emergency or specialty care to PEC.

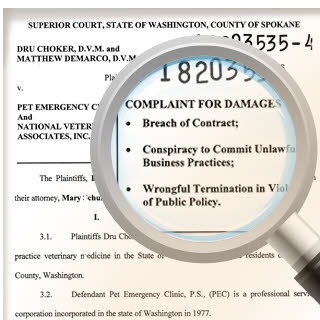

Choker and DeMarco responded with a lawsuit against PEC and NVA, alleging that the two institutions were making a joint attempt to monopolize emergency veterinary services in Spokane — the largest city in Eastern Washington — by imposing noncompete and mandatory referral requirements on employees and stockholders.

The lawsuit and the story behind it highlight the contentious nature of noncompetes — contracts, usually with a former employer, that bar an employee from working for a competitor or starting a competitive business.

While noncompetes are used in many industries and professions in the U.S., state laws dictate how they're enforced. In recent years, several states have moved to restrict their reach. Last October, for example, Massachusetts began limiting noncompetes to one year and prohibiting employers from enforcing noncompete agreements against employees who have been fired or laid off.

Lawmakers in Washington state, where PEC is located, are considering legislation to prohibit noncompetes for employees earning $100,000 or less, limit any agreements to 18 months and require employers to cover wages of workers during the period they are barred from working.

The lawsuit against PEC and NVA also draws attention to professional divisions arising as veterinary emergency and referral clinics, serving a critical role as hubs for after-hours and advanced veterinary care, become businesses worth millions of dollars that attract large corporate suitors eager to expand into new markets. Many such conflicts have not been reported widely because they typically are settled quietly, said Dr. Lance Roasa, a Nebraska-based veterinarian and lawyer who represents companies acquiring veterinary practices. Roasa is not involved in the Spokane case.

That lawsuit, if successful, could suggest a more confrontational path for those who are unhappy about the wave of consolidations. The suit brought by Choker and DeMarco is pending in Spokane County Superior Court but already has prompted NVA to suspend the acquisition.

Meanwhile, NVA is countersuing the two veterinarians, alleging they harmed the company by interfering with its effort to acquire PEC.

PEC, through its attorneys, declined to comment as did NVA officials. In its court response to the Choker and DeMarco complaint, NVA denies it could have imposed a noncompete agreement and mandatory referral obligation, given that its agreement with PEC was non-binding.

The following narrative is based upon interviews with Spokane-area veterinarians, some of whom are PEC shareholders; and an email received by PEC shareholders and obtained by the VIN News Service. The email describes the hospital's situation in detail. Most veterinarians who agreed to interviews did so on condition of not being named because of the close-knit nature of the veterinary community in Spokane and the contentiousness of the topic.

Born from a collaboration

PEC was established in Spokane in 1977 as a professional services corporation. Like many emergency clinics that popped up throughout the country in the 1970s and 1980s, PEC was established by veterinarians in the region who were tired of being on call. Each invested $2,000, the equivalent of $2 a share, with little expectation the emergency clinic would ever make a lot of money. Now, when clients called Spokane clinics after hours, their answering machines would offer the phone number of the newly established Pet Emergency Clinic, operated by two full-time doctors.

Over the years, many Spokane-area veterinarians bought shares in PEC as a way of supporting the community. Share prices, set annually by an accounting firm based on an established formula, rose virtually every year to the current price of about $370. Management was overseen by a board that met monthly.

The clinic was a great success. "The way it was created to have the local community of veterinarians be the shareholders was a brilliant game plan," said a former PEC veterinarian. "It brought a sense of community and stability to our local veterinary family. We all knew, trusted and respected each other. Treating patients was a team effort between regular vets and the emergency vets. There was continuity and accountability of patient care as we transferred patients."

As the business grew during the next four decades, the staff of emergency veterinarians grew. They were paid based on production, and as demand was strong and fees rose, so did their wages.

In 2016, PEC moved out of a small, inexpensive 39-year-old building into a new $4 million, 16,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art building. "We were crazy busy, seeing record numbers of cases and bringing in huge amounts of revenue," said the former PEC veterinarian.

To the after-hours emergency clinic was added a daytime referral business that housed specialists in surgery, radiology, clinical pathology and internal medicine, some of whom leased space in the building. Others were on PEC's payroll. More staff and higher costs increased business pressures and created tension. Soon, cracks in the foundation of PEC appeared.

When an internist in the referral business who was paid not much more than $100,000 a year was told PEC could not afford to give her a raise — at the same time that some emergency doctors were earning $250,000 a year — the PEC board recognized that it had a problem on its hands.

At the end of 2017, Dr. Linda Wood, then president of the PEC board, wrote at length to shareholders about issues at the emergency clinic. Wood noted that in 12 of the 19 months between February 2016 and October 2017, the clinic spent more money than it brought in. Fees were increasing 3 percent every six months, she wrote, and some "no longer seem reasonable."

One PEC shareholder confirmed to VIN News that the rates had become unaffordable to many. "I have had to euthanize animals because my clients can’t afford to pay [PEC rates]," the veterinarian said.

Dr. Annie Bowes operates a clinic in Post Falls, Idaho, a 20- to 40-minute drive from Spokane, depending on traffic. Some of her clients, she said, were deterred from PEC because of its prices. She told VIN News about one whose dog needed surgery for pyometra, a life-threatening infection of the uterus. PEC quoted $1,900 to do the procedure.

The client then took the dog to Bowes, telling her that if the surgery cost more than $1,400, she'd have to euthanize the animal. Bowes charged $1,200. Veterinary fees tend to vary widely depending on the region; Bowes believes PEC's fees were fueled by a lack of competition in the Spokane market.

Faced with growing internal tensions, the PEC board hired VetSupport Consulting Services in April 2017 to audit clinic business. The consultancy raised a number of issues, including: veterinarian salaries that accounted for 36 percent of revenues, compared with a national average of 25 to 29 percent, and contributed to PEC's high fees; the lack of a full-time practice manager; and "the negativity and culture of the practice."

Wood explained in her letter that during the review process, a major shareholder, "seeing the multiple difficulties with the practice," asked the board to reach out to NVA to see if it was interested in acquiring PEC. Sometime during the summer of 2017, PEC began discussions with NVA regarding a possible sale.

As the two parties negotiated a non-binding letter of intent, word spread that NVA was willing to pay as much as $900 a share for the emergency clinic. The shareholders who owned 1,000 shares, the maximum allowable number for one individual under PEC bylaws, had the potential to sell their respective stakes for $900,000.

The money was attractive to many, but others worried that the sense of trust and cooperation between PEC and surrounding clinics would be lost. "Having a corporation own an emergency clinic that used to be owned by veterinarians changes the conversation," said one veterinarian who voted against the deal.

Veterinarians who work for corporations say they definitely have quotas they need to meet, said the shareholder. "As owners, we can tell [PEC] to put [a client’s] cat on IV fluids until morning. We could rely on them."

The shareholder worried that that reliability would diminish under the ownership of a large company. "Clients say [clinics owned by large corporations] nickel-and-dime you for everything. They look at the bottom line over the animal’s health."

The battle over PEC’s sale "created a bitter division," the shareholder said. "It was sad because it pitted friends against friends."

Conflict intensifies

In October 2017, PEC decided to negotiate a decrease in salaries for the emergency doctors that, by some accounts, would have reduced some salaries — which maxed out at around $250,000 — by about half. The doctors also were required to sign a contract that included noncompete provisions. One source with knowledge of the negotiations said the decision to require doctors to sign the noncompete had nothing to do with the negotiations with NVA.

PEC's emergency doctors saw it differently. "We six PEC doctors felt that signing the PEC contract, including the noncompete clause, was putting a big 'gift bow' on us to be delivered to NVA at the time of purchase," a veterinarian said. "Not one single one of us was happy about the contract or its implications. And, not one single one of us wanted to sign the contract."

Of the six doctors, one resigned and two were terminated for refusing to sign the contract. Nearing retirement, one emergency doctor decided to stay with the practice for another year or two. Two others signed the noncompetes because they were concerned about financial security. Two internists on the payroll also signed the noncompete, although one later relocated. Other restructuring efforts resulted in the departure of an office manager of nearly 30 years.

It was not until months later that the veterinarians who left PEC learned that PEC's non-binding agreement with NVA still would apply to them as shareholders. In the event that NVA acquired PEC, those veterinarians who left would have to sell their shares, and under the terms of the proposed agreement, would be prohibited for five years from practicing after-hours emergency medicine outside of PEC. Shareholders at other clinics would be required to refer all their clients to PEC.

Choker and DeMarco hired Mary Schultz, an attorney in Spokane. Schultz previously had success representing employees who believed they were unfairly terminated, according to an article in the local Journal of Business. On Aug. 13, 2018, Schultz filed a complaint in Spokane Superior Court, alleging that PEC and NVA aimed to monopolize emergency veterinary services in Spokane through a noncompete covenant that would "adversely affect its employees' ability to earn a living."

"[PEC] started as a clinic for the local vet community," Schultz told VIN News. Because so many local veterinarians owned shares, "when you attach a noncompete to employees, and then the stockholders are required to do mandatory referrals, you have captured the entire network."

Schultz contends that the noncompete was being used "to increase the value to the corporate takeover, to grease the skids to allow the corporation to monopolize the veterinary services."

Schultz said she's witnessed a similar dynamic in human medicine, where exclusive referral agreements can trigger federal anti-kickback laws. Such laws are designed to "protect people from deal-making between hospitals and physician practices that restrict professional judgment or result in unnecessary services and escalation of cost or procedures that can cause damage to medical care," she said.

Schultz called the noncompete requiring Choker and DeMarco to practice outside a 25-mile radius for five years, and the application of the noncompete to all shareholders, "pretty aggressive on the part of PEC and NVA."

Roasa, the Nebraska-based lawyer and veterinarian, believes Schultz could have a difficult time persuading a judge that the plaintiffs should get damages based on actions proposed in a non-binding agreement between NVA and PEC. The argument that the two organizations were seeking to monopolize the local emergency pet care market also could face an uphill battle, in Roasa's assessment.

"There are a lot of practices that have effective monopolies," he said. And courts generally have accepted the need for corporate buyers to protect their assets via noncompete agreements.

However, Roasa thinks Schultz could have a strong argument that applying noncompete restrictions to DeMarco and Choker as shareholders is unreasonable.

"Spokane is like an island, and 25 miles encompasses most of that area," said Roasa, who sometimes teaches at Washington State University's veterinary school in Pullman, 75 miles from Spokane. The commercial center of Eastern Washington, Spokane, population 217,000, is surrounded by farmland and sparsely populated towns.

"You can’t expect someone to drive two hours to work at another job," Roasa said. "Veterinarians need to support their families, so the court could side with the veterinarians in that respect."

Schultz expects the case to come to trial in 2020. Meanwhile, Choker and DeMarco have established an emergency pet clinic about 35 miles away in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, population 50,000. It opened this month.

As for PEC, it's unclear whether the practice will be sold to NVA or another corporate consolidator. One veterinarian who remains fiercely loyal to the hospital worries that things will never be the same there.

"I fear that employee loyalty is gone and what will replace it is the profit-driven corporate world with its revolving door of employees," the veterinarian said. "The shareholders may gain financially, but the patients, the clients and the local veterinary community will suffer the consequences."

May 6, 2021, update: Drs. Dru Choker and Matthew DeMarco sued in federal court in November 2020, folding their state claims into a federal antitrust lawsuit. In March 2021, the United States District Court Eastern District of Washington denied Pet Emergency Clinic’s motions to dismiss. A trial date has not been set.

This story has been changed from the original to correct an error in Dr. Lance Roasa's law office and veterinary practice location.